Tzar Oluigbo (Lead writer)

When Dorothy (not her real name) arrived at work that morning, she was already in pain. The public-school teacher lives with sickle cell disease, a chronic condition that requires regular hospital visits and a strict treatment plan. That morning, the pain progressed while she was in the classroom, worsened by her menstrual period. “I told them that I have sickle cell disease and that when it is time for my check-up, they should allow me to go. They initially agreed. But when the time came, they denied me,” she said, referring to the school management.

What followed was a medical emergency that exposed how fragile access to care remains for millions of Nigerians living with chronic illness, without insurance or savings. “Later that day, they came to my house with a supervisor. He told my mother that I am not fit to return to the classroom,” Dorothy recalled. Her experience reflects a wider reality in Nigeria’s health system. When care is paid out of pocket, illness can become both a financial and social punishment.

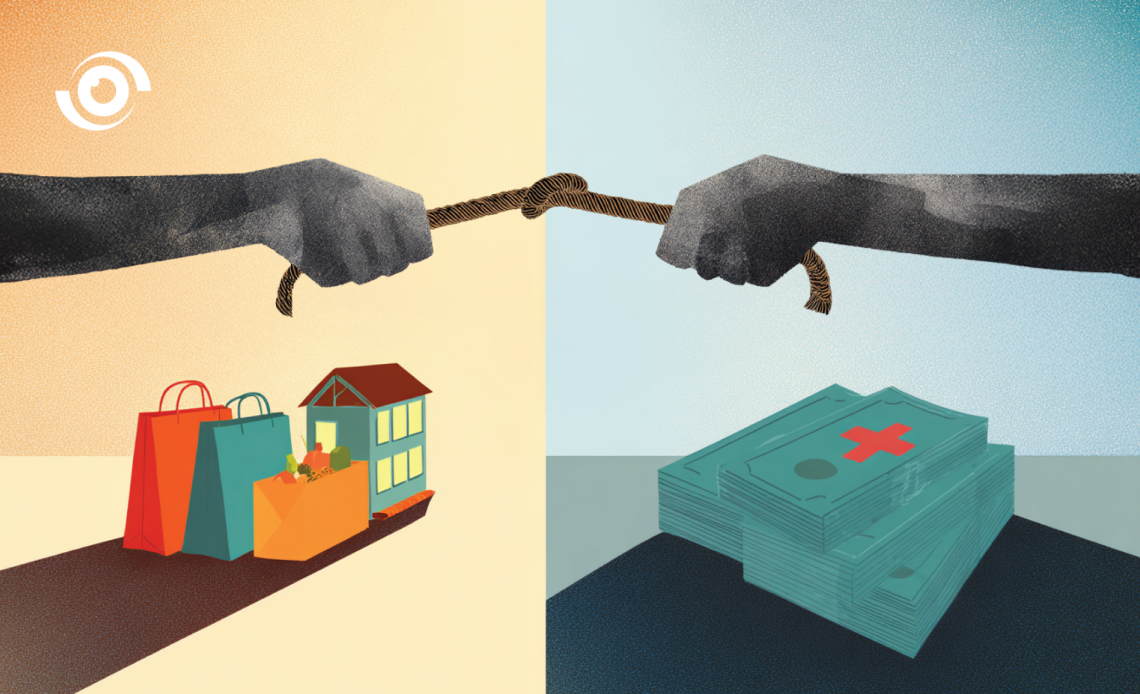

When families choose between health and daily survival

At the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) in Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State, hospital administrators say they see this dilemma daily. Families arrive already stretched thin, forced to choose between food, school fees, rent, and drugs. “When health costs are paid out of pocket, families are forced to choose,” said Prof. Theresa Nwagha, Chief Executive Officer of the UNTH Foundation. “Many patients cannot complete treatment because they simply cannot afford it. Some even remain admitted for months because they cannot pay their hospital bills,” she added.

This “tug of war” between daily survival and healthcare costs does not affect only patients; it also strains public hospitals that are already underfunded. During her time overseeing laboratory and radiology services, Prof. Nwagha said it was common to find patients who stayed in wards for over a year because they owed millions of naira. “The hospital has already spent resources it cannot get back while providing care, yet we cannot abandon them,” she said.

A Foundation born from a systemic gap

At UNTH’s campus, patients who are medically fit for discharge sometimes remain in hospital because they cannot pay their bills. In December 2021, UNTH Foundation was created as a non-profit initiative led by the hospital’s Chief Medical Director, Prof. Obinna Onodugo, to respond to this growing crisis. “Healthcare financing is not what it should be in Nigeria, and tertiary hospitals are not funded the way they should,” Prof. Nwagha said. “The Foundation was created to bridge this gap by working with individuals, organisations, and partners who want to support indigent patients”, she added.

Through its Indigent Patient Fund, the Foundation supports patients who cannot afford emergency surgeries, essential drugs, and hospital bills that delay discharge. According to UNTH social welfare records from 2025, over 40 percent of patients fall within this indigent category, a statistic that reflects both widespread poverty and systemic financing gaps. Although operationally independent, the Foundation works closely with hospital departments to identify patients who genuinely cannot afford care. A verification checklist is used to confirm financial vulnerability, including evidence of no current employment (or a separation notice if the patient lost a job within the past three months), no income, no savings (verified with a bank statement), no unemployment benefits, and a supporting statement from the person providing accommodation for the patient and their family.

How the system works on the ground

For Dr. Florence Onuoha, Indigent Patient Welfare Manager at the Foundation, the work goes beyond paperwork. “Working with indigent patients demands empathy and patient-centred care,” she said. “They desire treatment, but they simply cannot afford it; from laboratory to food and even basic toiletries.” Patients are identified through doctor and nurse referrals, ward rounds, and social welfare assessments. The Foundation then triages cases to prioritise those with the most urgent needs.

However, funding alone does not always guarantee immediate care. “Sometimes the funds are available, but the hospital pharmacy is out of stock, so the medicines we rely on are not available when needed, which hampers our effort to care for indigent patients,” Dr. Onuoha added, highlighting supply chain challenges that continue to affect public hospitals like UNTH.

Initially, much of the Foundation’s work focused on settling accumulated hospital debts. Through partnerships, including support from De Imperial Philanthropic Family (DIPF), over ₦28 million has been mobilised to clear bills and restart stalled treatments for over 77 indigent patients. But the model soon revealed its limits. “Why wait until someone becomes critically ill and then raise a large sum of money,” Prof. Nwagha asked, “when that same money could cover 10 to 20 people under health insurance?”

In Nigeria, one emergency hospital visit can cost two to ten times more than a basic annual health insurance premium, showing why pre-paid cover and stronger risk pooling are far cheaper than paying cash at the point of care. This shift in thinking led to the launch of the Hope for Health programme, which provides one-year National Health Insurance coverage for people living with chronic conditions such as sickle cell disease, haemophilia, diabetes, and hypertension. In its first campaign, the Foundation covered 10 beneficiaries. The aim of the initiative is to remove the financial fear that discourages early hospital visits and reduce long-term indigence. “It introduces beneficiaries to the benefits of health insurance, helping to gradually reduce their dependence on emergency bailouts,” Prof. Nwagha said.

Chronic illness and catastrophic spending

For Chinwe Obiekwe, Director of Physiotherapy Services at UNTH, the Foundation reshaped what compassionate care looks like inside the hospital. “One of the hardest things for healthcare workers is seeing lives that can be saved, but the patient has no money or insurance,” she said. “When patients stay admitted because they cannot pay, they occupy bed space and may become vulnerable to hospital-acquired infections.” She believes awareness is as important as funding. “We need wider public awareness in places of worship, markets, and through community leaders so that people present early before complications set in.” She said this is an area the hospital and partners should strengthen.

Image credit: Nigeria Health Watch

Charity Amarachukwu, a physiotherapist and sickle cell advocate, says the economic burden of chronic illness pushes many families into long-term poverty. “People living with sickle cell disease spend over 40 percent of their income on care. Many are denied employment, which makes post-treatment care even harder,” she said. While the UNTH Foundation’s insurance offers relief, she argues that long-term relief depends on broader reforms. “The true solution is universal health coverage. One year of insurance is helpful, but it is not enough on its own.” For beneficiaries like Dorothy, the Foundation’s support translated into immediate relief. “It’s a relief for me,” she said. “Most sickle cell warriors don’t work and don’t have a steady income. The Foundation has made it easier by covering most of the treatment fees.”

What the model gets right

The UNTH Foundation reduces financial barriers to care through a structured, hospital-integrated approach. By working directly with clinical teams and social welfare units, it helps ensure that support goes to verified patients who genuinely cannot afford treatment. The model also tackles bed blockage, a less visible consequence of poverty. When patients are medically fit for discharge but cannot pay, beds stay occupied and hospitals lose capacity. By settling bills and clearing discharge delays, the Foundation improves bed turnover and makes space for other patients waiting for care.

Where the gaps remain

The Foundation’s impact also highlights the limits of philanthropy in a system with low insurance coverage, weak social protection, and heavy reliance on out-of-pocket spending. Its work depends on donations and staff contributions, which can shrink during economic hardship, even as need grows. “To keep the Foundation running, UNTH staff now contribute through a voluntary one percent salary pledge scheme. Since the current leadership took over in July 2025, staff participation has grown by over 370 percent,” Prof. Nwagha said. “We are trying to move from emergency charity to sustainable health financing support.”

The Foundation is also working to broaden its support base, including stronger engagement with University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN) alumni. Prof. Nwagha said the team is building a database of alumni who have actively supported UNTH, the College of Medicine, and the Foundation since its inception, with plans from 2026 onward to deepen and coordinate that leverage.

Bridging the present while waiting for reform

The UNTH Foundation shows how a hospital-linked fund can be structured with clear criteria and oversight. It shows that when hospitals, communities, and donors collaborate, financial hardship does not have to translate into denied care. But it also raises a critical question on how can models like this can be complemented by system-wide reforms that reduce the number of patients who need emergency financial rescue in the first place.

Until Nigeria expands its health insurance coverage, strengthens social protection, and funds public hospitals more reliably, the UNTH Foundation will remain a stopgap. Its model helps patients settle bills and leave the hospital on time. But philanthropy cannot deliver universal health coverage. Without reforms that reduce out-of-pocket spending, the need will keep outgrowing the support available.