Olatunde Olaoluwa and Sonia Biose (Lead writers)

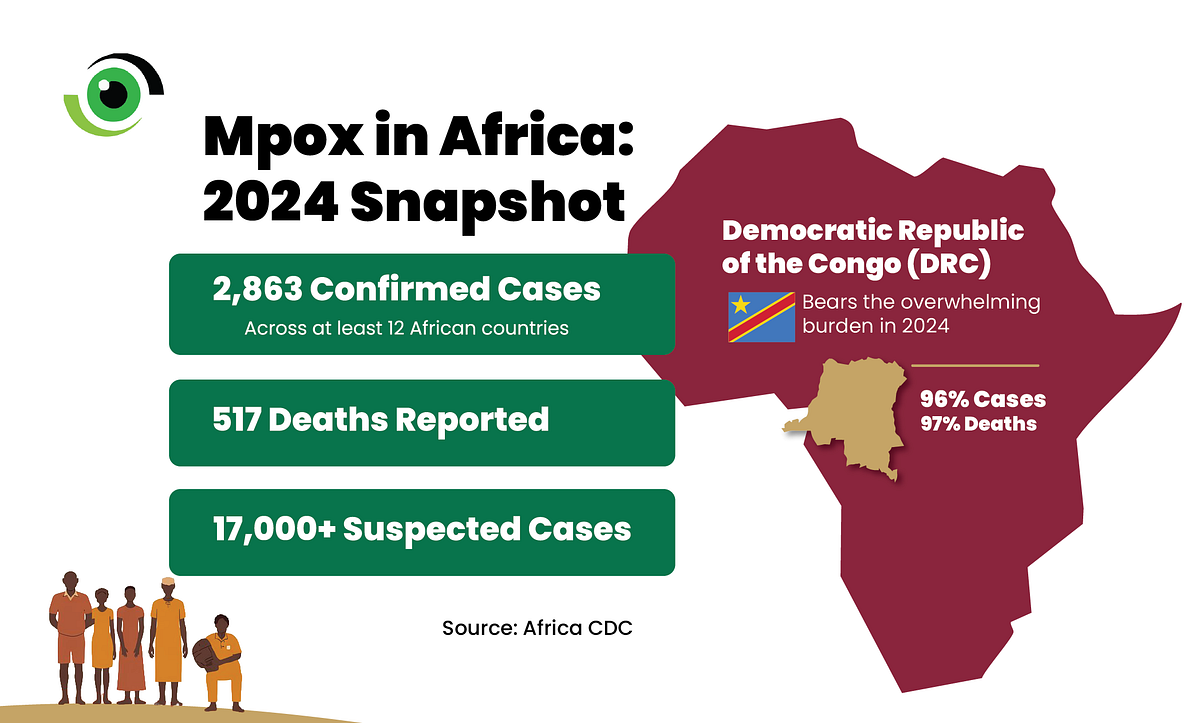

For the first time since the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was established, the agency used its expanded mandate under the revised 2022 statutes to declare mpox a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security (PHECS) in August 2024. The PHECS is a continental alert that enables Africa CDC to coordinate a unified response, mobilise resources, and support Member States to contain cross-border threats. The declaration reflected a worsening outbreak. As of 13 August 2024, at least 12 African countries had reported mpox outbreaks, with 2,863 confirmed cases and 517 deaths, while suspected cases exceeded 17,000.

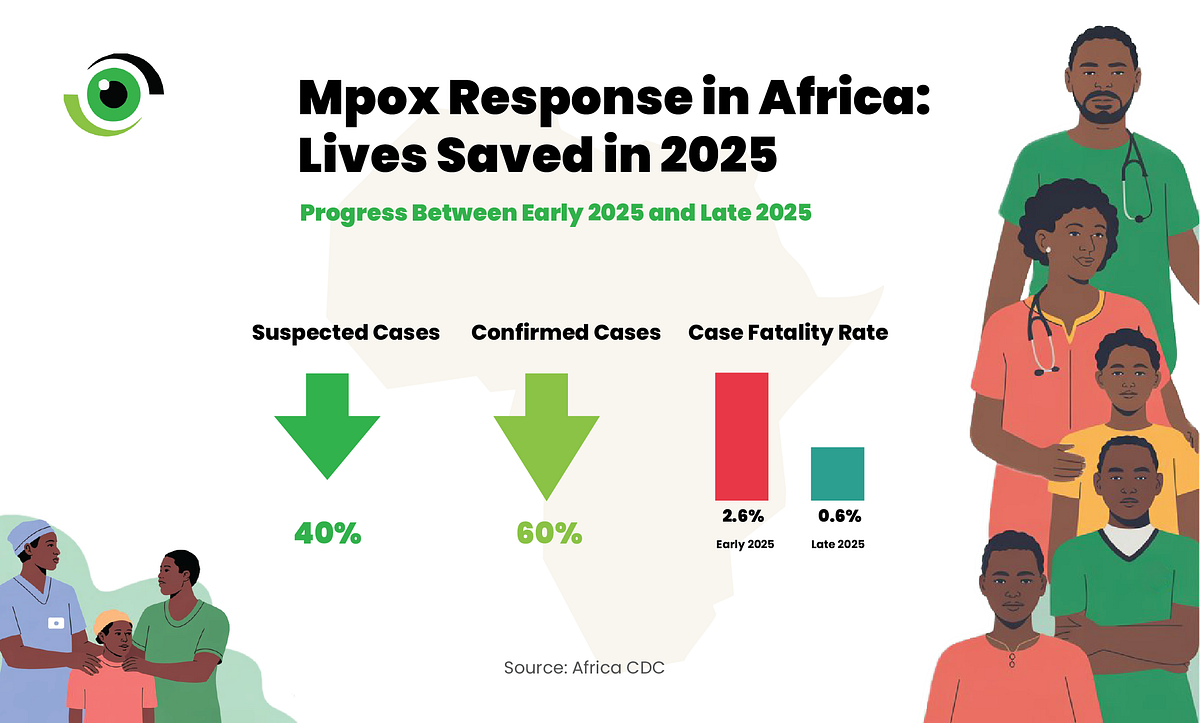

But the bigger question was always what happens when the emergency label is removed. By 22 January 2026, the landscape had shifted. Following recommendations from its Emergency Consultative Group, Africa CDC announced the lifting of mpox from PHECS status, citing sustained improvements in surveillance, laboratory capacity, clinical care, risk communication, and regional coordination. The results were measurable. Between peak transmission periods in early 2025 and late 2025, suspected cases fell by 40% and confirmed cases by 60%, and the case fatality rate among suspected cases declined from 2.6% to 0.6%. But lifting the PHECS is not a signal to relax.

It is a handover from emergency architecture led through the Incident Management Support Team (IMST) to sustained, country-led control through National Public Health Institutes (NPHIs) and Ministries of Health, embedded in routine surveillance and primary care. This transition is a real test of Africa’s New Public Health Order, whether the continent can sustain core capabilities such as financing, workforce, laboratories and genomics, supply chains, and accountable leadership, once the emergency pressure eases.

According to the Africa CDC, the response secured over US$1 billion in pledges from governments and donors and expanded genomic sequencing through an EU-backed partnership designed to strengthen laboratory diagnostics and improve sequencing capacity. Partners such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) also supported vaccine research and clinical evaluation during the outbreak, helping to generate evidence on vaccine effectiveness and strengthen Africa’s preparedness for future mpox flare-ups. The question now is whether those gains become routine infrastructure rather than a one-off mobilisation.

Why clades matter and why surveillance cannot drop

Mpox is not a single, uniform threat. Different viral clades and subclades can differ in transmission patterns and outcomes. Clade IIb drove the multi-country outbreak that began in 2022, while clades Ia and Ib have fuelled growing outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and other African countries, with clade Ib detected beyond Africa. The implication is that surveillance must remain sensitive enough to detect both zoonotic spillover and shifts in sustained human-to-human transmission, especially in settings where testing, specimen transport, and cold-chain logistics remain fragile. Community-based alerting, rapid access to testing, and cross-border event-based surveillance must not weaken. If specimen transport, cold chain, and last-mile logistics are given lower priority, delays will widen, and the virus can spread undetected in hard-to-reach areas.

Defining the strategic pivot and why vigilance still matters

From August 2024 to January 2026, Africa’s response was built for speed. Surge teams, emergency financing, and central coordination were set up to interrupt transmission and reduce deaths. The post-PHECS phase must be built for endurance, integrating mpox into routine surveillance, laboratories, infection prevention and control, and targeted vaccination where risk remains highest. Operationally, this means a shift from the Africa CDC-led IMST model to national ownership through NPHIs and Ministries of Health, supported by clear performance indicators and predictable domestic financing. A particularly vulnerable phase of outbreak control is often the downgrade, when political attention shifts and financing becomes less certain.

During the acute phase, countries and partners pledged over US$1 billion to support the response. The risk now is donor fatigue and domestic under-budgeting. Member States should convert emergency spending into routine budget lines for surveillance, laboratory systems, infection prevention and control, and targeted vaccination. This sustained investment is especially critical in hotspot areas and border towns, where population movement can accelerate cross-border transition. Without coordinated surveillance and joint outbreak response between neighbouring countries, gains made during the emergency phase can quickly erode, delaying recovery.

Risk communication, trust, and the next research agenda

Once the formal emergency designation is lifted, perceived risk can fall faster than biological risk. The transition roadmap should therefore put Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) at the centre, clearly communicating that this is a shift from emergency response to sustained control and recovery, not the end of the threat. Vaccination remains central, but this longer phase depends on stronger evidence on duration of protection, priority populations, and vaccine performance as the virus evolves. Research and surveillance must therefore continue, especially in high-burden settings and among vulnerable groups.

The coming months will test whether Africa can sustain the infrastructure built during the emergency without the urgency of a continental alert. Africa CDC has indicated that lessons from the mpox response will be institutionalised across other epidemic-prone diseases, including cholera, diphtheria, measles, and polio, anchoring the Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness, and Response (PPPR) agenda. If Member States finance and integrate these capabilities into everyday systems, Africa will not only respond faster to the next outbreak, but also prevent more outbreaks.