Onyedikachi Ewe and Vivianne Ihekweazu (Lead writers)

Last week, Nigerians were confronted with a heartbreaking video of a heavily pregnant woman in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, walking the streets unaware that she was already in active labour, desperately seeking help. She was spotted by a concerned citizen who stopped to ask why she looked so worn out. What followed was a devastating reflection of the deep cracks in our health system that continues to cost lives.

The woman explained that she was carrying twins, yet had been told to bring N28,000 (approximately $18) and a referral letter from her clinic in Mpape before the hospital would admit her for delivery. With no money, she walked kilometres in the heat to collect the referral letter. The concerned citizen helped her return to the health centre and even bought her basic supplies, but by the time she returned to the hospital, she had lost her twins. While the exact details of what went wrong remains undisclosed, it is clear, this was a preventable tragedy.

This is the kind of story that sparks momentary outrage online, and arm wringing, yet risks fading into silence as life moves on. In the same week, news also broke of a woman and her newborn who died after a caesarean section in Akwa Ibom. An incident that prompted the State Governor to inaugurate a panel of inquiry. These deaths cannot be normalised. Each death reflects a system that is failing the very people it is meant to protect.

Maternal and newborn deaths in Nigeria

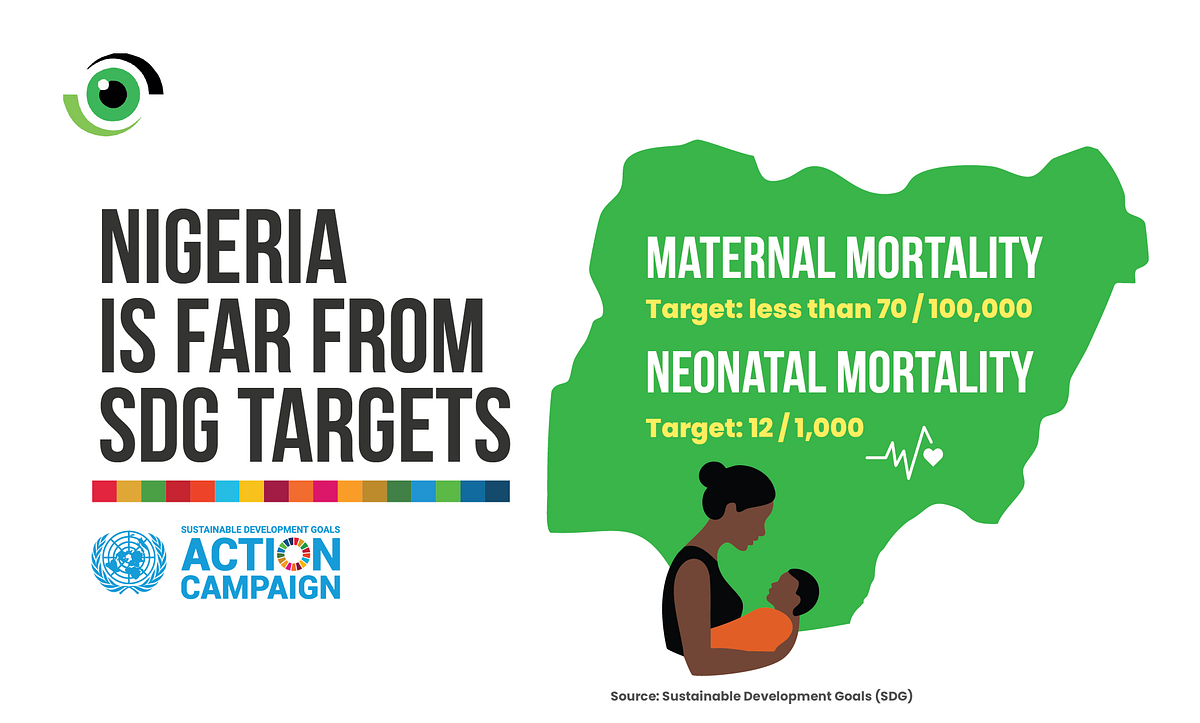

Nigeria continues to record very high rates of maternal, neonatal, infant and child mortality. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) call for reducing maternal mortality to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and neonatal mortality to 12 per 1,000 live births, yet, Nigeria remains far from achieving these targets.

That this tragic loss of these twins occurred in the Federal Capital Territory, the seat of government that should represent the best of Nigeria’s health system, underlines just how deep these problems run.

The Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response (MPDSR) system was institutionalised by the World Health Organisation, and later expanded by Nigeria’s Federal Ministry of Health to include child deaths, becoming the Maternal Perinatal Child Death Surveillance and Response (MPCDSR).

It requires that every maternal, perinatal or child death, be documented, reviewed, and used to drive action. However, we must ask, will this mother’s case be reviewed under MPDSR? And if it is, will the lessons lead to change to prevent a reocurrence , or will it remain another statistic filed away?

Accountability mechanisms must be strengthened through legislation and full implementation of MPDSR to drive action in preventing future maternal and perinatal deaths. Although national implementation of the bill has stalled, Lagos State is advancing a bill to formally establish and sustain the surveillance system.

A broken referral system

Barriers to geographical and financial access continue to prevent women from accessing timely care. However, efforts to reduce the burden of out pocket expenses to vulnerable households can be seen in the recent signing of the Memorandum of Understanding by the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) with three facilities in Lagos to catalyse access to Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (CEmONC) and formalise the agreement for the neonatal component of CEmONC. This direction, if scaled and fully implemented will reduce the financial burden for vulnerable households thereby improving maternal and newborn outcomes.

Unfortunately, even when women surmount these hurdles and arrive at the facility, there is a lack of preparedness and inadequate infrastructure at the facility to provide care. These barriers, compounded by a weak referral system from primary to secondary care and further on, creates a deadly cycle of delay. This case once again exposes the weakness in our current referral system.

In the video, the woman said she needed transportation to collect a referral letter from the facility she had registered in, before a hospital would provide her with care. A functional, digitised referral system integrated with the National Health Insurance Authority and the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) would have spared her this ordeal. She should not have had to run around for paperwork from Asokoro to Mpape, approximately 17-kilometre distance, while her babies’ lives hung in the balance. Health records need to be digitised and linked across facilities to ease bureaucratic delays.

A high-risk pregnancy, antenatal care and maternal nutrition

Twin pregnancies, like the case of this mother who tragically lost her babies, are considered high-risk and require close monitoring, specialised care, and timely intervention. This mother should have been identified, prioritised, and supported through antenatal care. Instead, she was left to navigate financial barriers and bureaucratic delays alone.

Focused antenatal care provides an essential opportunity for skilled health workers to monitor the course of pregnancy, take a detailed history, treat hypertension to prevent pre eclampsia, identify high-risk cases such as multiple pregnancies.

We must address the underlying vulnerabilities, such as malnutrition that often begin with the mother, are compounded by the physical stresses of pregnancy, and are tragically passed on to the baby, perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of poor health. The woman carrying twins looked visibly undernourished and was clearly highly stressed, factors that likely increased her risks. Access to Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation (MMS) is vital, reducing anaemia, low birth weight, and stillbirth, while improving survival chances for both mother and baby. A fair chance in life begins with a strong, healthy start.

Maternal undernutrition remains a silent crisis in Nigeria, with 1 in 5 women of reproductive age in Nigeria undernourished and anaemia affecting more than 60% of pregnant women. contributing to poor pregnancy outcomes and preventable deaths. The woman’s exhaustion on the streets of Abuja, her inability to afford baby items, and her trek to secure a referral would have compounded her stress levels, increasing her risks and ultimately cost her babies’ lives.

Another wake up call to protect our mothers and babies

In April 2025, we reported the story of Kemi. Similar occurrence both reported and unreported have continued to take place around the country everyday. This story, beyond just one woman and her lost set of twins, is about a system that continues to fail the most vulnerable that it should protect. It is about every Nigerian woman who faces pregnancy with fear, instead of confidence.

What action is needed?

To prevent stories like this from repeating, Nigeria must act decisively:

- Strengthen referral systems to prevent these recurring tragedies, both the structures that deliver care and the interventions that support healthy pregnancies. This includes ensuring seamless referral pathways between primary, secondary, and tertiary facilities. The use of digitised patient records, as seen in the FOR M(om) programme in Lagos, Delta, and Kano states, is a step forward. These digitised systems need to be interoperable so that patient information follows the woman across every level of care.

- Guarantee financial protection by scaling NHIA agreements on Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (CEmONC) beyond pilot states, ensuring that no woman is turned away for lack of funds. President Tinubu’s new directive ordering the mandatory implementation of health insurance must also prioritise vulnerable woman, especially expectant mothers. This is being done under the Delta State Contributory Health Scheme (DSCHC) Equity Health Plan.

- Prioritise maternal nutrition by expanding micronutrient supplementation, scaling up food fortification, and embedding community-based nutrition interventions.

- Institutionalise accountability by ensuring every maternal and neonatal death is reviewed under MPDSR and that recommendations translate into concrete, monitored action.

- Scale proven interventions like the Safer Births Bundle of Care, implemented in Tanzania and now expanding to Borno and Gombe States, which includes specialised training and re- training of health care workers. The programme has demonstrated 40% reduction in early newborn deaths and 75% reduction in maternal deaths in Tanzania and is already showing success in Nigeria. Interventions like this must be scaled nationwide.

- Empower women through education, employment, and inclusion in health decision-making, ensuring they have agency to seek care early and make informed choices. Data consistently show how women empowerment through education and employment influences behaviour and opportunity. In addition, removing financial barriers is critical, as costs remain one of the biggest obstacles to accessing timely care as tragically demonstrated in the case of the woman who lost her twins.

Addressing maternal, newborn and child mortality requires concerted, multisectoral effort. While the benevolence of the concerned citizen must be commended, no woman’s or child’s survival should depend on chance encounters with strangers. The Nigeria health system must deliver the care and protection that every mother and child deserves.

It is highly unfortunate that in this 21st century, women and unborn infants are dying due to a failed health care systems. And to think that so much money is being spent in meetings, workshops, conferences geared that is not adding any value to the system. That money spent on such failed engagements should be channel in bridging human resource gaps in primary healthcare, training and retraining of service providers, strengthening healthcare information systems etc. Government at national and Subnational levels should key into the recommendations of this article by health watch. Pregnancy and childbirth is not a disease and pregnant women should not die because of it

This is heart breaking!

I believe the government needs to investigate this matter.

the pain of loosing a child is not what a mother should experience not to talk of set of twins.

I just the Lord comfort the woman.

it is well

This case highlights how small but powerful and well-directed actions can prevent unnecessary maternal and neonatal deaths in Nigeria. I sincerely hope it won’t be business as usual because it’s simply unacceptable that this is happening in Nigeria in 2025. Thank you for a well written article.

This write up is quite impactful but it’s worrisome that Nigeria is yet to meet the SDG target as regards maternal and child health. My opinion is that community health insurance schemes and family/neighbors/friends support groups can go a long way to bridge this gap. It’s really devastating 😭

You can moderate my comment. Thank you