Hannah Ajayi (Lead writer)

Nigeria has set an ambition to end malaria as a public health threat and align with a malaria-free future by 2030. But targets do not save lives; delivery does. At Nigeria Health Watch’s Health Misinformation Fellowship, Odinaka Obeta Kingsley, a young advocate, described losing a friend’s 14-year-old son to malaria. That story should make us uncomfortable for one reason: malaria is preventable and treatable, yet it still kills. The question is no longer whether Nigeria cares about malaria; it is whether we will do the simple work of funding, procurement discipline, last-mile delivery, and accountability required to stop avoidable deaths.

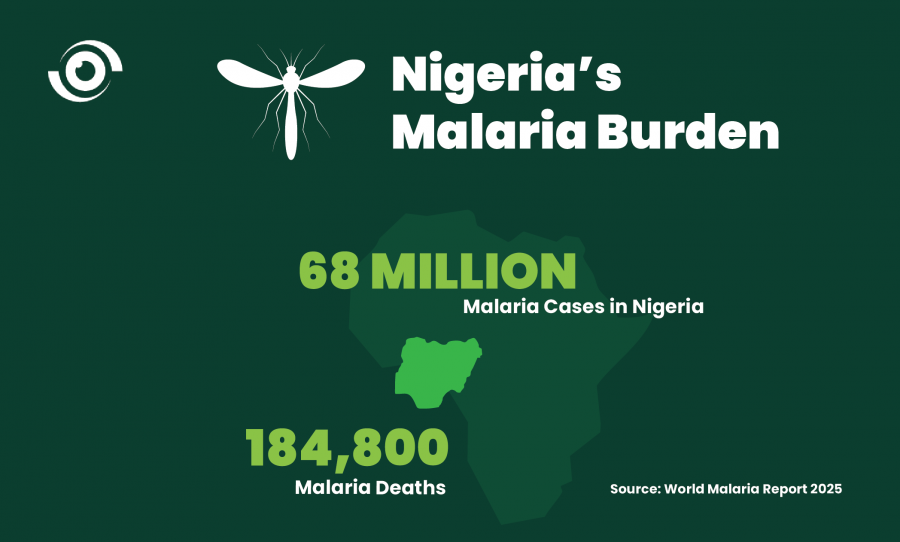

Odinaka founded Block Malaria Initiative to turn grief into practical community action. That instinct of moving from slogans to systems is exactly what Nigeria’s malaria response now needs. The World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report estimates that Nigeria had 68 million malaria cases and 184 thousand malaria deaths in 2024, the highest estimated national malaria burden worldwide. The tragedy is not only the scale; it is the predictability. When prevention tools exist, persistent deaths usually point to gaps in financing, commodity availability, access, and quality of care.

Why malaria still kills in Nigeria

Malaria persists in Nigeria because the conditions for transmission remain intact, and the last mile of service delivery is weak. Poor drainage, clogged waterways, and unmanaged waste create breeding sites, especially in dense, unplanned settlements. But the environment is only half the story. Many families still reach care late, face stockouts, or rely on informal providers. Insecurity and long travel times in conflict settings and hard-to-reach areas delay testing and treatment. Nigeria’s scale makes every intervention harder, distributing nets, sustaining behaviour change, ensuring every fever is tested, and keeping Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) continuously available. The point is not that Nigeria is too big; it is that Nigeria needs a delivery model that matches its size, data-led targeting, disciplined procurement, and strong community platforms.

Nigeria will not sustain progress by doing more of the same. More nets are not automatically better if mosquitoes are adapting. Nigeria must deploy the right nets for the right risk settings, plan replacement cycles, and manage insecticide resistance as routine policy, not as an emergency response. The same discipline is needed in case management to protect treatment quality, enforce test-before-treat, and watch for drug resistance by strengthening supervision and reporting. Because many Nigerians first seek care at patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) and chemists, the private sector must be brought into the system, trained, quality-assured, linked to referral, and enabled to report. None of this works without secure commodity stockpiles of RDTs and ACTs. Stockouts turn preventable malaria into deaths, so procurement and supply chains must be managed like critical infrastructure.

Nigeria’s current efforts and progress toward elimination

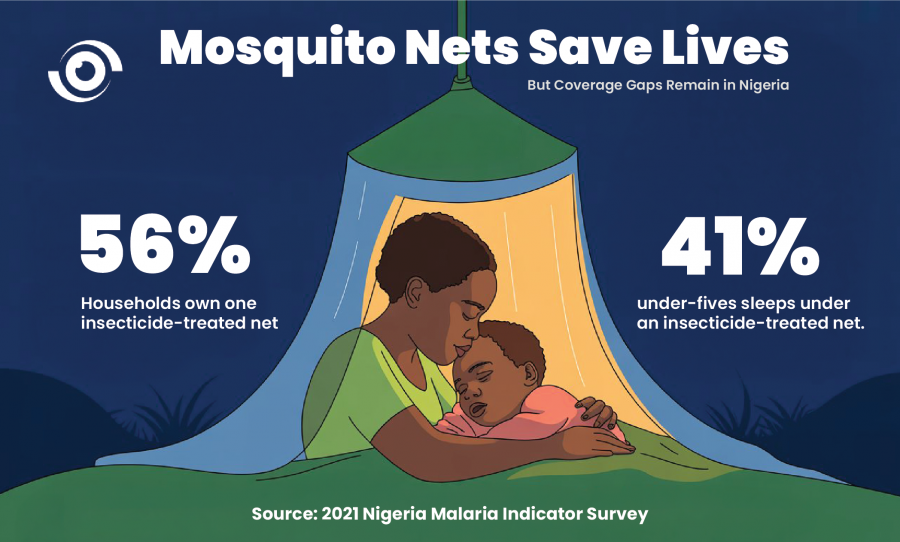

Nigeria’s response is not short of strategies or partners. The National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) coordinates national direction, while states deliver through their malaria programmes and primary health care (PHC) systems. Partners support commodities, technical assistance, and community mobilisation. Recent survey evidence shows both gains and stubborn gaps. In the 2021 Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey (NMIS), 56% of households owned at least one insecticide-treated net (ITN), but only 41% of under-fives slept under a net the night before the survey, showing that ownership does not automatically translate to use. The same survey found that among under-fives with fever, only about one in four had blood taken for malaria testing. This is a policy warning. Without routine testing, Nigeria cannot test, treat, track at scale, and without that, deaths remain predictable.

Malaria vaccines add a new layer of protection, and their impact will depend on Nigeria overcoming persistent challenges around vaccine access and coverage, as well as strengthening the routine systems that determine who actually gets protected. Nigeria began piloting the R21 malaria vaccine in Kebbi and Bayelsa in October 2024, with support from partners including Gavi and UNICEF. Early implementation updates reported substantial uptake. The bigger test, however, is whether the vaccine becomes fully embedded in routine immunisation, completing all required doses on schedule, tracking defaulters, and ensuring it consistently reaches the children most at risk rather than remaining a successful pilot in a limited number of states.

Lessons for Nigeria from other African countries

Nigeria does not need perfect conditions to make progress; it needs disciplined execution. Countries that have achieved malaria-free certification exhibit a consistent pattern of strong surveillance, free or affordable diagnosis and treatment, rapid response to every case, and robust border and import management. Algeria’s certification highlights the value of sustained surveillance and universal access to diagnosis and treatment. Egypt’s experience underlines the need for vigilance against imported cases and for integrated systems and rapid response. The lesson for Nigeria is not to copy this model. It is to learn what worked, how it was done, and to look to duplicate the fundamentals and treat malaria control as a continuous service.

What Nigeria must continue to do

Sustaining malaria gains in Nigeria requires a shift from periodic campaigns to everyday services. Three priorities stand out:

- Protect commodities and the quality of care. States must keep ACTs and RDTs continuously available, supervise adherence to test-and-treat protocols, and regulate the informal market so that families are not pushed towards ineffective or counterfeit treatment.

- Close the ownership-to-use gap. The 2021 NMIS shows that ITN ownership does not automatically translate to use. Behaviour change must be local, continuous, and tied to trusted community platforms, not only mass media.

- Target resources where they will have the greatest impact. In a tightening fiscal environment, Nigeria cannot afford uniform approaches. Stratification tools such as Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention targeting and Subnational Tailoring (SNT) must guide decisions on where to deploy nets, vaccines, chemoprevention, and intensified surveillance. With the Global Fund’s 8th Replenishment raising less than originally projected, efficiency and precision in delivery become as important as total financing. Tailored, data-driven interventions are a necessity.

Interventions must be supported by a clear operational plan that addresses the realities of insecurity and humanitarian settings. Above all, sustaining progress will require predictable and sustained funding, with federal and state budgets allocating adequate domestic resources to malaria interventions. This must be accompanied by public accountability mechanisms, including tracked and timely fund releases, reliable commodity availability, consistent testing, and quality-assured treatment.