Safiya Shuaibu Isa and Chibuike Alagboso (Lead writers)

As 2025 draws to a close, this review captures the lessons of a year that exposed Nigeria’s dependence on external health funding and the reforms now required. The early 2025 pause in external funding and the donor reprioritisation that followed underlined a hard truth. Nigeria’s health security cannot be built on financing decisions made elsewhere. Yet the year also showed what firmer governance can achieve, including emergency domestic financing, stronger coordination through a Sector Wide Approach, and primary health care funding linked to measurable performance. The message for 2026 is clear and practical. Government should fund approved health budgets in full and release them on time, make health insurance enrolment and compliance enforceable, and publish what is allocated, released, and spent, alongside the results delivered. It should treat primary health care as the bedrock of national resilience, invest in local production, and publish programme data every quarter in a form citizens can use.

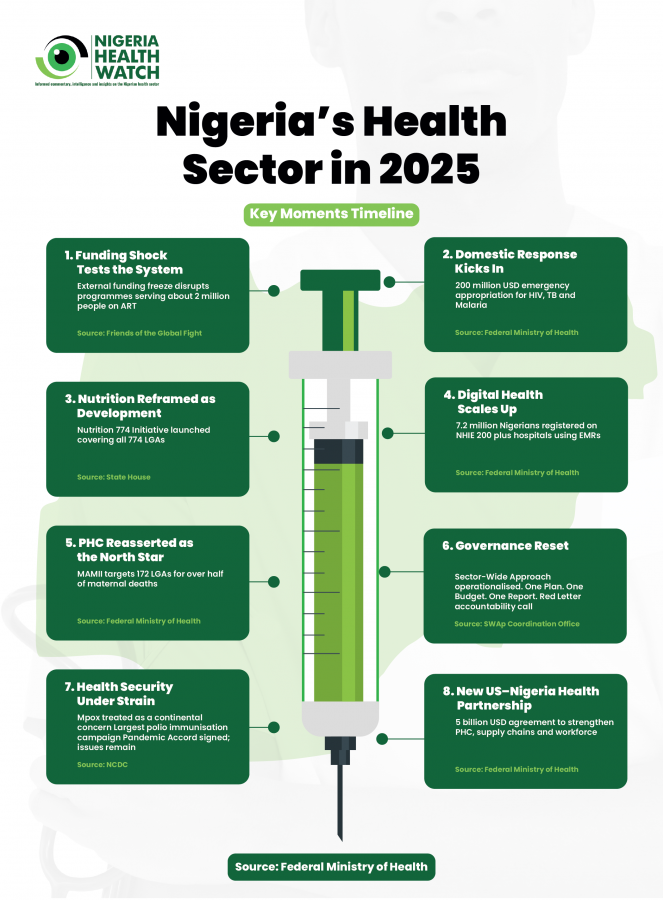

2025 was the year Nigeria’s health system confronted the hard truth that the global safety net is no longer guaranteed. As overseas development assistance (ODA) declined and major donors turned inward, long-standing assumptions about predictable funding were upended. In January 2025, Nigeria Health Watch cautioned that Nigeria could no longer treat external financing as a safety net for its health system. Development assistance was already declining, and the signals were evident. Weeks later, a new U.S. administration issued a series of executive orders that temporarily paused official development assistance, and signalled a shift in global priorities.

Looking back, 2025 stands out as a year of disruption and early signs of system change. It showed that when resources tighten, progress depends less on volume of funding and more on alignment with sound policy and disciplined implementation. This review does not attempt to capture every development. Instead, it reflects on what 2025 demanded across health system quality, governance, health security, and the health value chain, and what these lessons mean as Nigeria moves into 2026. As Nigeria steps into 2026, a year likely to be defined by electioneering, competing national priorities, and increasingly fragile global attention, this article examines what this moment demands of those committed to protecting and advancing hard-won health gains.

Quality health systems turn crisis into catalyst

The January 2025 funding freeze and stop-work orders exposed deep vulnerabilities. Programmes supporting roughly two million Nigerians on antiretroviral therapy faced disruption, while vaccine and nutrition supply chains came under strain. The message was clear; a quality health system cannot depend indefinitely on external support. The response, however showed what is possible under pressure. Working through the Ministries of Health and Social Welfare, Finance, and Budget and Economic Planning, the Federal Government approved an emergency appropriation of US$200 million for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. This was a short-term bridge, not a long-term solution, but it demonstrated the capacity to mobilise domestic resources when health is treated as urgent.

Reforms addressing underlying drivers of poor health outcomes also continued. The launch of the Nutrition 774 Initiative (N774) reframed malnutrition as a multisectoral challenge spanning health, livelihoods and productivity across all 774 local government areas (LGAs). Investments in digital systems gained traction, with over 7.2 million Nigerians registered on the National Health Information Exchange. Yet health outcomes remain the true measure. Reducing preventable maternal and child deaths remains non-negotiable. Initiatives such as the Maternal and Neonatal Mortality Reduction Innovation Initiative (MAMII) focused on the 172 local government areas bearing the highest burden, reinforced the central role of strong, functional primary healthcare. Without resilient PHC systems delivering quality care close to communities, broader reform will not endure. This was reaffirmed as a priority at the 64th National Council on Health.

Governance and financing are at a turning point

Governance reform gained momentum in 2025. By August 2025, the Federal Government operationalised the Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp) to health, moving from fragmented planning toward a unified framework anchored on One Plan, One Budget, One Report. The SWAp sought to replace parallel planning, donor-driven verticals, and siloed accountability with a unified national strategy and performance framework. By the end of the year, 35 of 36 states and the FCT had conducted Joint Annual Health Reviews, aligned their operational plans with the National Health Sector Strategic Blueprint, and appointed National Health Fellows and Public Financial Management Officers across all 774 local government areas.

A defining moment came in September 2025 with Nigeria’s inaugural National Health Financing Policy Dialogue, convened by the National Insurance Authority (NIHA). A key outcome was a presidential directive mandating NHIA enrolment across Ministries, Departments and Agencies, embedding health insurance compliance into public sector systems. If enforced, this has the potential to expand coverage while strengthening accountability and transparency in health financing. Nigeria’s reforms also echoed a wider continental shift. The Africa Health Sovereignty Summit and subsequent Accra Reset, convened by the Ghanaian Head of State, His Excellency President John Dramani Mahama in 2025, sought to advance the growing African consensus on health sovereignty, calling for a shift away from aid-dependent models toward nationally owned systems grounded in strategic financing and accountable governance.

In this context, Nigeria’s SWAp and health financing reforms can be read not as isolated policy choices, but as part of a broader recalibration of how African health systems are governed. This push also brought into focus the need to explore innovative financing tools such as health taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) to mobilise resources locally. Governance reform in 2025 extended beyond coordination and financing into accountability. In October 2025, the Federal Government launched Basic Healthcare Provision Fund 2.0 (BHCPF 2.0), shifting from a flat allocations model to a performance-linked model. Facilities were tiered by utilisation and outcomes, with digital tracking, published disbursements, and biometric verification, introduced to reduce leakages. This was accompanied by direct disbursement of ₦32.9 billion to 8,000 primary health centres. The Coordinating Minister of Health’s “Red Letter” reinforced accountability as a shared responsibility between government and citizens.

Health security and epidemic preparedness

Nigeria’s health security efforts in 2025 continued to rest on the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC), which sustained surveillance and response efforts across multiple public health threats. The year unfolded within a broader continental and global context. Mpox had already been declared a WHO public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) in August 2024, making a period focused on sustaining and scaling coordinated delivery. Nigeria’s concentrated on maintaining surveillance and outbreak response, strengthening cross-border alert systems, and aligning risk communication and operational coordination with the Africa CDC health security agenda. These efforts continued until WHO determined in September 2025 that the mpox upsurge no longer constituted a PHEIC.

In parallel, Nigeria intensified immunisation to reduce outbreak risk and close persistent immunity gaps, including efforts to contain circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus. This culminated in an integrated vaccination campaign launched in October 2025, targeting roughly 106 million children with measles-rubella and polio vaccines, alongside routine immunisation goals. Globally, adoption of the WHO Pandemic Agreement signalled progress towards stronger international cooperation on pandemic preparedness and response. Yet, shifts in global engagement, including the United States’ renewed “America First” framing raised concerns about weakened coordination. As Nigeria looks to 2026, effective health security will depend not only on functional national institutions but sustained real-time data sharing, and strong national institutions and effective regional collaboration in a more fragmented global environment.

From consumption to contribution

Progress along the health value chain also stood out. The African Medical Centre of Excellence (AMCE) moved from concept to care delivery, representing a strategic shift toward retaining specialised expertise and reducing outbound medical tourism. This momentum extended across the health value chain following last year’s Executive Order to increase local production of healthcare products. Through the Presidential Initiative for Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain (PVAC), plans to establish Africa’s first second-generation long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) manufacturing plant in Nigeria have been set in motion. Reinforcing Nigeria’s role from consumer to contributor within the global health economy.

This direction was reinforced by the signing of a five-year health cooperation Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Nigeria and the United States, designed to deepen bilateral collaboration and anchor reforms within a shared financing framework. Covering April 2026 to December 2030, the MoU anticipates nearly US$2 billion in grant support from the United States, alongside Nigeria’s commitment to mobilise nearly US$3 billion in domestic resources by allocating at least 6% of executed annual federal and state budgets to health. By explicitly linking external assistance to domestic financing reforms, the agreement signals a deliberate shift towards sustainability and reduced reliance on grants, consistent with Nigeria’s ambition to strengthen its position across the health value chain.

2026: The test of commitment

As political attention turns toward the 2027 general elections, keeping health at the centre of national priorities will require discipline and accountability. Primary Health Care (PHC) remains the clearest test. Experience from Yan Dadi PHC in Kano State, revitalised yet constrained by staffing gaps reinforces a persistent lesson: infrastructure alone does not deliver care.

Accountability must shift from rhetoric to routine practice. Delays in releasing the 2025 budget and instructions to MDA’s to rollover 70% of capital spending into 2026 raise fundamental questions about what resources were actually available and spent in the health sector this year. Budget allocations must be matched by timely release. Government should publish, quarterly data showing what was budgeted, what was released, what was cash-backed, and what was delivered, disaggregated by programme and by state. The credibility of the SWAp will depend on data integrity, including transparent evidence of how new cadres, including health fellows, have improved planning, spending controls, and frontline performance.

The funding freeze of early 2025 is a stark reminder that Nigeria’s health system is too important to outsource to donor cycles. This is not a rejection of partnerships, but a recognition that primary responsibility for Nigeria’s health security must rest with Nigerians. Emergency domestic appropriations, renewed momentum toward local pharmaceutical production, and growing consensus around financing health from within, including through health taxes, signal this shift.

2025 showed that progress is possible even under constraint. Whether those gains endure will depend on choices made in 2026. Nigeria Health Watch remains committed to celebrating what works, questioning what does not, and amplifying the voices of those who depend on the health system every day.

In 2026, Nigeria must move beyond commitments to measurable delivery through timely, cash-backed budget releases, better-performing PHCs, expanded NHIA coverage, and faster outbreak response. Let health be the policy choice Nigeria refuses to postpone, because lives cannot wait for the next budget cycle.