Orphanages are not uncommon in Nigeria and across different parts of the globe. The United Nations Convention on the rights of the child makes it clear that a child has the right to care and protection if they are adopted or in foster care. It also stipulates that a child has the right to special care and help if they cannot live with their parents. This makes orphanages a source of refuge for many children orphaned or made homeless for a variety of reasons.

Due to budgetary constraints, providing food for children in orphanages is largely dependent on freewill donations from individuals and organisations, especially during festive periods. “About 90% of all the food our children consume is provided by charitable gifts”, says Mr Charles Ikezemuoka, who runs the Divine Wounds of Jesus Orphanage Home and Rehabilitation Centre (DWOJOHRC) located along Arab Road in Kubwa, one of the outskirt towns of the Federal Capital Territory. His orphanage houses over 130 children, including those orphaned and displaced by the Boko Haram insurgency in the North East of Nigeria.

In January 2019, the Divine Wounds of Jesus Orphanage Home and Rehabilitation Centre was the recipient of a different kind of charity. Young leaders from the Mandela Washington Fellowship Alumni Association paid them a visit, and although they came bearing the usual gifts, they also taught Charles and his caregivers how to prepare nutritious foods for their children with everyday food items they usually take for granted.

Malnutrition: An Elusive Problem

The impact of good nutrition goes beyond the individual as it significantly rubs off on the economic fortunes of a nation. On the contrary, malnutrition — which in this case is undernutrition — is a widespread problem, affecting people of all ages, especially women and children. It has remained a daunting issue for the global health and development communities and in Nigeria, the numbers are not very encouraging.

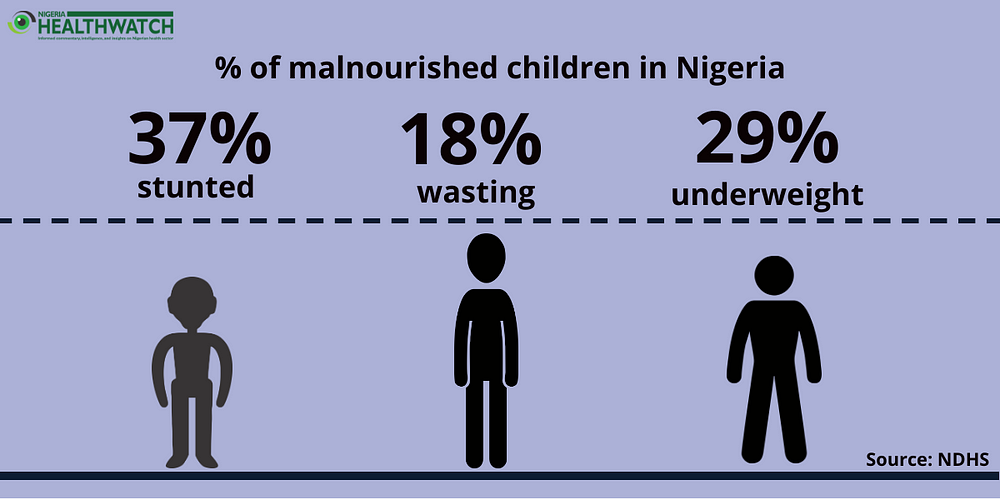

While there are various unverified reports about the data for stunting in Nigeria’s children, key findings from the National Demographic and Health Survey 2013 (NDHS 2013) estimate that 37% of children under age five are stunted, 18% wasted and 29% underweight. Stunting refers to impaired growth and development in children as a result of poor nutrition while wasting, also referred to as low weight-for-height or thinness usually indicates a recent and severe process of weight loss, which is often associated with acute starvation. Adequate nutrition is essential for a child’s optimal physical, mental, and cognitive growth, health, and development, especially during the period from conception to age two — also known as the first 1000 days.

Malnutrition is not only a function of not eating enough to nourish the body, but also ensuring that food consumed contains enough of both micro and macro nutrients in appropriate amounts to help the body perform optimally. It takes intentional effort to tackle and prevent malnutrition because a child may be eating a lot of food, yet still be in danger because the food has little to no nutritional value. This makes the problem elusive on inception and difficult to treat until it begins to manifest.

Recognising the importance of proper nutrition, both local and global investments have been made to tackle the menace of malnutrition. Global initiatives like the World Food Programme are helping to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Two, Zero Hunger by 2030 by ensuring that over 90 million people around the world have access to food. They also deliver food assistance in emergencies and work with communities to improve nutrition and build resilience. In 2017 the World Bank developed an investment framework for nutrition aimed at showing the investment needs for reaching the global targets for stunting, anaemia, breastfeeding and wasting. The benefit-cost analyses showed that every $1 invested to treat stunting returns $11, while $4 is the return for the same amount invested to treat wasting.

In Nigeria, efforts to teach community members to use local food sources to provide high nutrient and cost effective feeding for their children proved to be extremely effective in Kano State. Other initiatives include the Federal Government’s homegrown school feeding program, referred to as Africa’s largest national school feeding programme, and the National Policy on Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) which took cognizance of motherless/adopted infants and young children. Overtime, these efforts possibly led to the improvement of nutritional status of children in Nigeria between 2008 and 2013 as shown in the last NDHS as the proportion of children who are stunted declined from 41% in 2008 to 37% in 2013.

However, there hasn’t been substantial progress since then, especially in North East Nigeria where there have been incessant security challenges. The 2018 National Nutrition and Health Survey showed that the prevalence of stunting in Nigeria was 32% and the burden has remained above 30% since 2014, with many states in the North West and North East recording prevalence above 40%.

A Simple Solution

The visit to DWJOHRC orphanage was part of a national initiative by the Alumni Association aimed at not only providing food items for orphanages, but educating their care givers on low budget balanced diets. It was called Project Nourish and was successfully implemented across four states — Gombe, Enugu, Lagos, Bayelsa — and the Federal Capital Territory, in January 2019.

In Abuja, the team of fellows from four different cohorts arrived dressed in yellow aprons worn over white T-shirts. They came ready to join the caregivers in the kitchen to show them how to prepare low budget nutritious meals for the children. After a tour of the place and handing over the relief and food items, the caregivers gathered in a room used as a refectory to learn the basics of proper nutrition in a session delivered by Janet Gbam, a Fellow of the 2017 cohort. The presentation was prepared by Dr. Anita Benson, a medic member of the team and used in all the states where the project was carried out. She taught the caregivers low budget Nigerian foods that are rich in protein, carbs, fats & oil, vitamins and minerals. Some of the foods listed includes millet, wheat flour, oats, walnut, potatoes, and vegetables. There was also a section on the recommended daily intake of water & the caloric requirements of children based on their age. The presentation listed some nutritious Nigerian food options that cost about N300 per meal per child. One is a meal they fondly call “concoction rice” made from rice, palm oil, fish/crayfish, onions and pepper. The caregivers were shown how to make fortified pap for children at risk of malnutrition using guinea corn, milk, blended crayfish, groundnut, palm oil and sugar.

Another fellow, Lawrenta Igoh, gave a practical demonstration of how to prepare Tom Brown, a highly nutritious alternative to some canned cereals for the infants using combination of soya beans, groundnut and crayfish. Her session stirred interest among the caregivers as they asked questions on the processes, cost, and how to preserve the food.

While this was going on, another group, a mix of caregivers and fellows, was busy in the kitchen preparing lunch for the kids. The fellows showed the caregivers and other grown up girls in the orphanage who sometimes help with the chores how to make a more nutritious meal of moi moi, a popular Nigerian delicacy made from ground-bean paste. The meal was fortified with proteins sourced from fish and eggs.

Sustaining the gains of Project Nourish

“Even though the project appears simple, it benefited the children and caregivers in Bayelsa state”, says Virture Oboro, who led the project in the State. It helped the caregivers understand the essence of planning healthy meals for not just the kids but for themselves, particularly as some of the care givers were older and equally needed to improve their dietary and feeding habits. She also said that the impact of the knowledge gained was more than the food items they distributed and hoped that the orphanages that have benefited from this project continue to implement all the lessons learned.

The initiative was even more important for Ikezemuoka, who says knowledge from the training has helped them minimise cost while also providing the children with nutritious meals. This is because, with the same amount they spend daily on a meal (approximately N25,000) they can provide more nutritious food.

Lamide Johnson, president of the association said the motivation to embark on the project was fuelled by the zeal to tackle a social problem by addressing the root cause. He said their objective is simply to show that, “while it’s important to give fish to someone, it is much better and sustainable to teach them how to fish”.

However, it will take a lot more than goodwill to sustain the project. As a one-off project, there wasn’t a plan in place to check adherence of care givers overtime and determine long-term impact on the children. While some of the meals are highly nutritious, like adding eggs and fish to the moi moi are not very cheap and would require significant investment to sustain.The costed National Strategic Plan of Action for Nutrition (2014–2019) recognises that attaining global development goals and meaningful economic progress will not happen without an urgent improvement in nutrition. It also emphasised the need to scale up nutrition interventions that have proven to be cost-effective, feasible and with high impact.

This therefore presents these limitations as opportunities to build on the gains of the project by rethinking charity, especially for orphanage homes. Individuals and organisations can change their giving strategies by sponsoring the delivery of farm produce to these orphanages. This will enable them to have access to cheaper options of local and nutritious food contents. There are orphanage homes that have gardens, poultries and fish farms. These can be supported, and capacities of caregivers built to operate theirs.

While Ready to Use Therapeutic Foods (RUTFs) are useful especially in the management of children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in conflict zones, there should be efforts to prevent malnutrition by educating caregivers to leverage on locally available and affordable food sources with high nutritional content.