By Chibuike Alagboso and Ikemefuna Igwe (Lead writers)

Gandirwawa Primary Health Centre (PHC) is in Minjibir Local Government Area (LGA) which is 42 kilometres from Kano city in Kano State. Located on an expanse of land the size of almost four football fields, the PHC is usually bustling with activity: children running around, as their parents access health services ranging from routine immunisation to antenatal services.

In an office, the facility’s officer in-charge, Amina Muhammad, is attending to three women. All three women have two things in common: they are residents of Gandirwawa community, and they had all used the Wearable Immunisation Alert (WIA) wristband, which helped remind them of their children’s vaccination dates.

Despite the critical role of immunisation in preventing mortality in children below five years, caregivers still find it difficult to adhere to their children’s vaccination schedule.

Unmi Idris, a 23-year-old mother of two didn’t need much convincing because she understood the importance of vaccination. Her rambunctious son, Abdullahi Idris, never missed any of his vaccination appointments.

Naima Hamzat learned the benefits of vaccinations the hard way, when she didn’t keep to the vaccination appointments with her first child, her daughter was more at risk of diseases like measles and the common cold. It was a different story with her other three children, who barely fell ill, as she kept the appointments more religiously.

But, while both mothers understood the benefits, they sometimes struggled with remembering the days of their appointments.

Amina Muhammad’s challenges are different, “I have my monthly and annual targets for vaccination coverage,” she said, but with her facility serving over 140 settlements and most of them being hard to reach, it can be a difficult task taking vaccines to the communities.

Sometimes, they organise outreaches to these communities, but even that is not enough. “Even those close to the facility default, so we use the voluntary community mobilisers and village chiefs to mobilise the mothers to come to the health facility,” she added, revealing that with the implementation of the WIA pilot project in 2018, the women mostly came on their own to access vaccination services for their children. The project was implemented by Sydani Initiative for International Development in partnership with the Kano State government, with support from Grand Challenges Explorations an initiative that seeks to find innovative solutions to solve global health challenges.

What changed?

It started with an existing relationship with the Kano State government working across local governments and communities, said Sunday Atobatele, an Associate Principal and Director of the Human Capital Development Centre at Sydani Initiative for International Development. They developed and deployed the WIA with support from the Grand Challenges Explorations.

Atobatele said they identified the problem because they were already working in the state and started thinking about solutions that would help caregivers remember to adhere to vaccination schedules. This quest birthed the Wearable Immunisation Alert band, a simple electronic, silicone-based wristband that flashes a light to remind caregivers of their immunisation sessions.

The WIA’s usability doesn’t depend on phones or other devices owned by the caregivers as is the case with some mobile health solutions such as SMS reminders for vaccinations. The WIA starts illuminating intermittently a day before an appointment is due and continues until the caregiver takes the child to the healthcare facility. It is then reset by the health workers for the next appointment.

The health workers were trained on how to do this by Sulaiman Umar and Fatima Sharif, the project assistants in the state. “They don’t need to own a mobile phone. They don’t need to read any text message reminders. They don’t need any training. All they need to know is that when the light starts flashing, it’s time to take their child for vaccination,” Atobatele said.

Collaboration played a key role in the success of the product design and deployment. The initial consideration was for babies to wear the wrist band and for it to illuminate and make beeping sounds. But after running the idea by the communities, the Sydani team realised that the bands could constitute a choking hazard. The beeping sounds could also interrupt their sleep. The bands were tested for weeks before deployment.

To ensure 100% acceptance, Sydani worked with key stakeholders such as the state’s health ministry, and the Kano Emirate Council Committee on Health (KECCoH), to get their buy in. “Because we ensured everybody was fully carried along, when we got to the local governments to meet the health officers and village heads, they had already been informed to expect us,” Atobatele said.

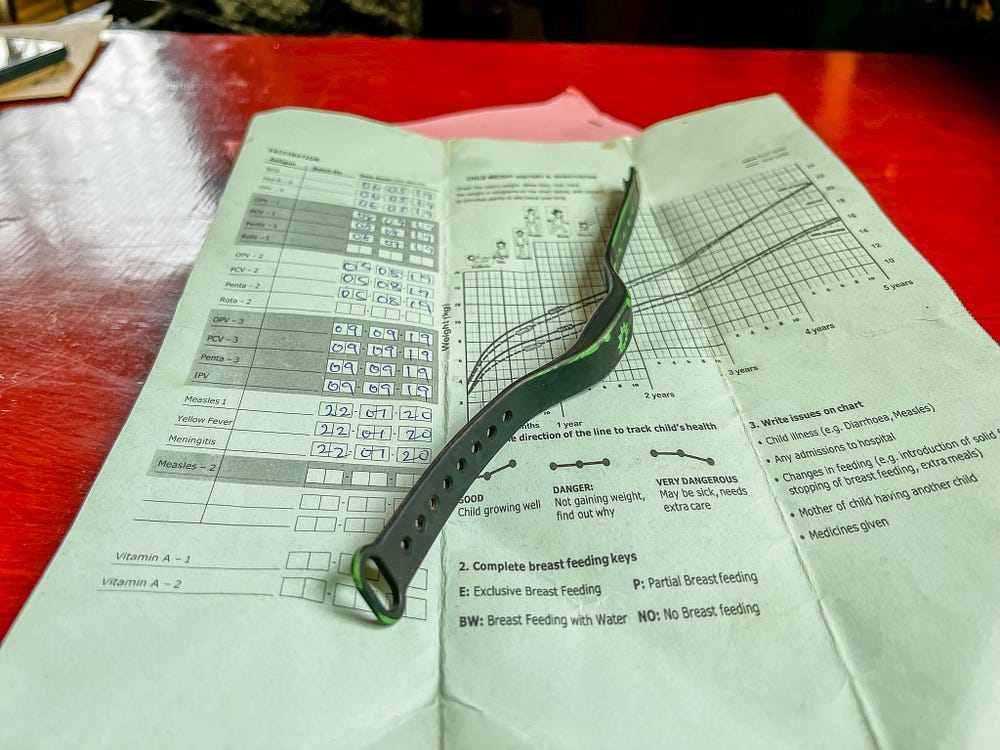

Since the intervention served as a pilot to determine the effectiveness of the WIA, they had a control group that didn’t receive WIA but had access to the full vaccination. After using a simple random sampling method to select the caregivers, the team distributed a total of 757 WIA wristbands across four health facilities: two in Minjibir LGA and two in Gezawa LGA.

According to Muhammad, the wristbands became a shining example as women in the communities were curious to learn where the caregivers received theirs, and this drove many of them to the facility. For the duration of the project, she didn’t have to worry about meeting her vaccination targets and organising outreaches, because they voluntarily and consistently came. This also led to a reduction in wastage because once opened, the vaccine containers must be discarded, even if only one dose had been administered.

Umar, who served as the project assistant team lead, said one of the challenges he faced was the lack of technical know-how of some other assistants. The project didn’t start off with just him and Shari, but as others were dropped due to performance. he had to learn to manage the remaining facilities with Sharif. This worked out well because he already had a good relationship with the facility heads.

Perhaps the biggest challenge faced with implementation was data quality, Atobatele said. While they could easily track data coming out of the project, they needed to have a historical perspective of the vaccination rate in the selected facilities, “When we work, we want to leverage our capacities to strengthen the health system, so we needed to have a retrospective understanding of the timeliness of vaccination in these places,” he said. The records were mostly on paper, so they were either defaced, destroyed, or lost.

The pilot phase provided proof that the wristbands can help improve compliance to immunisation schedules, but the phase has since ended. To ensure sustainability and scale up activities from the pilot to a fully operational phase, Atobatele said they are having conversations with potential partners, including the state government to adopt and possibly increase the reach of the intervention.

According to the Nigeria Strategy for Immunisation and PHC System Strengthening [NSIPSS], the country has 4.3 million unvaccinated children, the highest in the world. The 2016/2017 multiple indicator cluster survey (MICS) revealed that 77% of children aged 12–23 months did not receive all routine immunisations. It is therefore important for governments and stakeholders to continue deploying all strategies to ensure that immunisation coverage and uptake continues to increase.

This innovation is highly appreciated if can be scale to other state like my state Gombe