Over the years, Nigeria has developed various initiatives aimed at improving Primary Health Care (PHC) delivery in the country. One of such initiatives was the Primary Health Care Under One Roof (PHCUOR) programme, launched in 2011 and designed to improve primary healthcare services through the integration of all PHC services delivered under one authority.

The Minimum Service Package (MSP) is one of the nine components of the PHCUOR which is aimed at providing a strategic focus for investment in the key areas of human resource for health (HRH), infrastructure, and equipment in PHCs. This will be done through effective mobilisation and utilisation of available resources to deliver the best quality care possible.

Kano State’s path to MSP

Kano State has made significant investments into strengthening healthcare systems, especially primary health care, in the state. Their investment in routine immunisation and health systems strengthening, boosted by support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Aliko Dangote Foundation, strengthened health systems including the immunisation value chain across the state. To improve financing for health, the Kano State government in 2016 established two new agencies — the Kano Health Trust Fund, funded through 5% of the state’s internally generated revenue and 1% statutory allocation from the 44 Local Government Areas (LGAs) and the Kano State Contributory Health Care Management Agency (KSCHMA) established to guarantee access to high-quality, affordable healthcare to all people in the state. To further improve the delivery of Primary Health Care services, in 2021, the state government also recruited and deployed 56 medical officers to 44 local government areas in the state.

In 2019, the Kano State Primary Health Care Management Board (KNSPHCMB) with support from the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), and other partners — the United Nations Children’s Trust Fund (UNICEF), Solina Center for International Development and Research (SCIDaR) — began the operationalisation of the MSP with the development of an 8 year, 3 phased, costed plan. But, according to Bashir Sanusi, Director of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, KNSPHCMB, for the MSP to be implemented effectively, an assessment of 484 PHC facilities in the state was to be carried out to identify critical gaps in the three core areas of HRH, infrastructure, and equipment as specified by the MSP policy.

A situation analysis

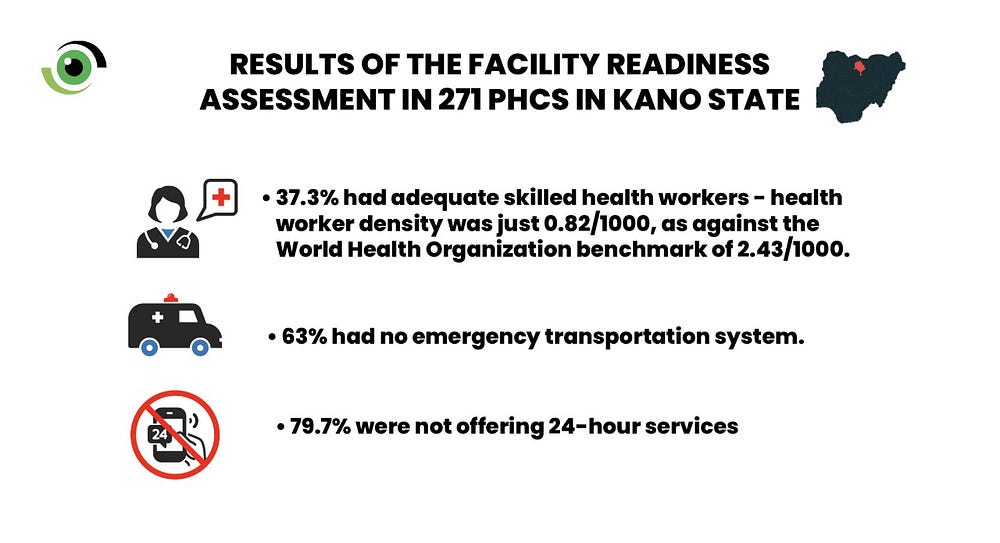

In 2021, with technical support from CHAI, the state established the MSP Monitoring Team (MSPMT) under the KNSPHCMB to oversee the MSP implementation in the state. The MSPMT conducted a facility readiness assessment across 271 of the 484 apex PHC facilities to establish a baseline for the commencement of the MSP implementation in the state. Idris Nuhu, coordinator of the MSPMT said the assessment revealed huge gaps and disparities among the facilities assessed. “There were gaps in every aspect, from health workforce to infrastructure to equipment. Only 37.3% had adequate skilled health workers, the health worker density was just 0.82/1000, as against the World Health Organization benchmark of 2.43/1000,” he said.

Nuhu added that none of the 271 assessed facilities had the minimum required equipment and drugs required by the MSP, and only about 1% provided the full complement of required MSP services. In addition, 63% had no emergency transportation system and 79.7% were not offering 24-hour services.

Getting to work

KNSPHCMB selected 46 PHCs with the highest traffic, across the state’s 44 LGAs, to pilot the operationalisation of the MSP. According to Bashir Sanusi, facility engagement visits were conducted to the 46 facilities, and with the help of each facility’s health workers and host community members, specific improvement plans were developed for each facility.

They focused on ensuring an upgrade of equipment, especially diagnostic equipment; renovation and provision of structures to house laboratories, and dispensaries; and providing adequate health workforce by training health workers on service delivery, including patient interaction, antenatal and postnatal service provision, procurement of medicines and consumables and healthcare management.

Steady progress in Garko and Kunya PHCs

“We have done so much since September 2021 when the first engagement visit was done,” said Baffa Nasiru, the officer in charge of Garko PHC, in Garko LGA. Garko PHC is one of the 46 facilities where the MSP operationalisation programme is being implemented. Nasiru revealed that at the time of the visit, the facility had only three delivery beds, a dilapidated labour room and a poorly equipped laboratory. However, since then, the delivery room has been renovated with a brand-new toilet attached to it. Three more delivery beds have been bought and equipment — a centrifuge, pulse oximeter, drip stand and nebulizer — provided for the laboratory and other departments.

In addition, the health workers were trained and five ad-hoc staff, including a midwife, were engaged to address the inadequate staff strength at the facility. According to Nasiru, before the intervention, the facility had only five permanent health workers and 10 ad-hoc staff and it was a challenge to provide 24-hour services as the PHC serves more than 20 communities. The additional ad-hoc staff brought the staff strength at the facility to 20 and this is helping to bridge the service delivery gap, he said. For Bilkisu Aliyu, the officer in charge of the labour room, the remodelled labour room with its brand-new toilet has made it more comfortable for her and her colleagues to work and has led to increased facility deliveries at the PHC.

In any intervention, getting the buy-in of community members is critical as it will, not only improve demand for services, but also instil a sense of ownership in the people. That is exactly what the MSP programme is achieving in Garko community. At inception in September 2021, the community members, including members of the Ward Development Committee (WDC) were trained on how to advocate for interventions in their community. Following the training, WDC members advocated to businessmen from their community who helped fix the PHC’s ambulance and renovated their staff quarters which had been unihabitable for many years. “Two of the three midwives in this facility are living in the renovated quarters, so anytime a woman is in labour, she can be brought here and be attended to,” said a visibly proud Ibrahim Hassan, Garko WDC chairman.

The story is similar in Kunya PHC in Minjibir LGA, another of the 46 facilities. However, Kunya PHC had even more challenges than Garko PHC as, in addition to grappling with a shortage of health workers, the facility had no water supply and dispensary. It was also unable to provide 24-hour services. However, since December 2021 the facility has engaged eight ad-hoc health workers, built, and equipped a dispensary and constructed an underground borehole with an overhead tank. “We now operate for 24 hours, and we have taken delivery of several babies in the process,” said Idris Ibrahim, the officer in charge of the facility.

Funding the MSP

As demonstrated in Kunya and Garko PHCs, the MSP programme appears to be improving healthcare delivery at primary health care level, where it matters the most. To fund it, “we have utilised internally generated revenue, especially from laboratory tests and sale of drugs and consumables in addition to capitation from KSCHMA and the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) to carry out the interventions,” said Nasiru. The BHCPF is a sustainable funding model designed to improve basic healthcare delivery in primary health facilities in communities across the country.

However, a potential threat to the MSP implementation is inadequate fund release due to competing government priorities. Relying on capitation from the BHCPF, KSCHMA and the facility’s internally generated revenue means the programme might be implemented at a much slower pace, as the funds may not be sufficient to address the many issues that hinder the delivery of quality health care at PHC level.

Conscious effort should be made to ensure sustainable and sufficient funding for the Kano State costed Minimum Service Package. It is therefore imperative that the KNSPHCMB and partners carry out sustained advocacy to the Kano State government and other stakeholders to fund the programme and continue to improve the quality-of-service delivery at PHC level in the state.