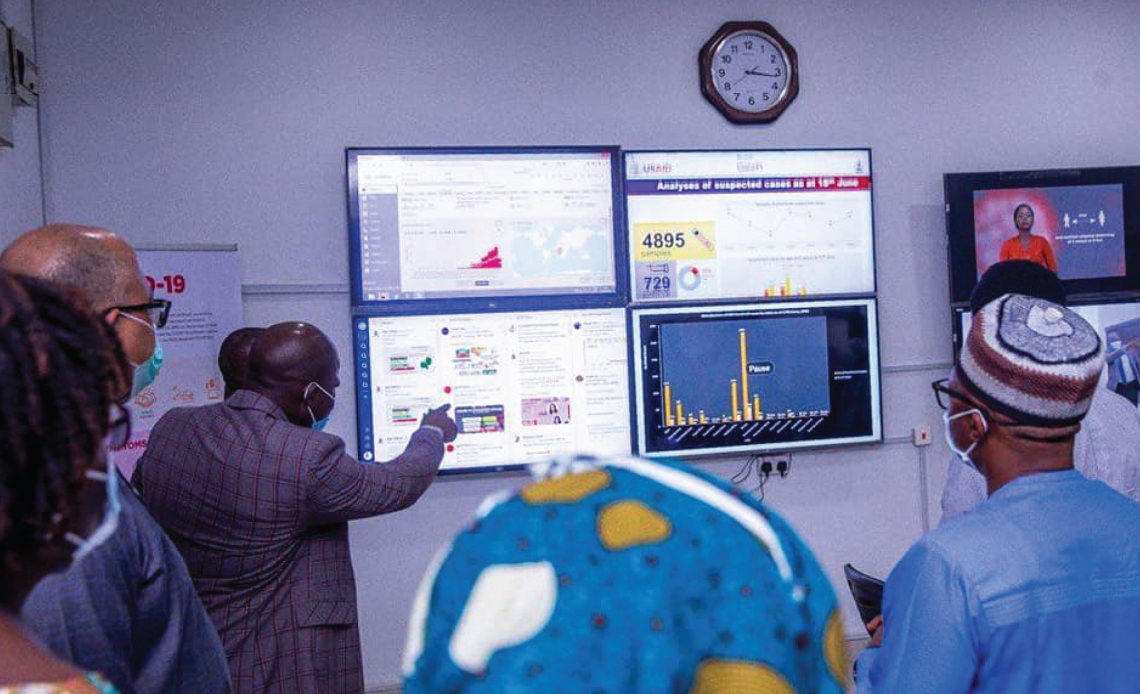

Over the past decade, Nigeria has made significant progress in strengthening its disease surveillance capacity, particularly through digital innovation. One of the most impactful tools has been the Surveillance Outbreak Response Management and Analysis System (SORMAS) first piloted by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (NCDC) to improve real time outbreak detection and response. SORMAS has since evolved into a nationwide platform that enables rapid case detection, contact tracing, and real-time data analysis.

The tool has been critical in managing responses to Lassa fever, COVID-19, and cholera outbreaks. Alongside SORMAS, the District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) and CommCare have become cornerstones for electronic routine data recording, monitoring, and analysis regionally, further strengthening Nigeria’s capacity for effective surveillance.

These efforts also reflect the Africa Centre for Disease Control’s (Africa CDC) broader vision for a continent connected through digital public health, as articulated in its Digital Transformation Strategy. However, technology alone cannot guarantee safety. Gaps in digital literacy, infrastructure, and community trust risk leaving millions behind. To build true resilience, Nigeria must complement innovation with inclusion, ensuring every community not only has access to these tools but can also use them to act on life-saving information.

The readiness gap we cannot ignore

As promising as these digital systems are, their effectiveness often meets the realities of Nigeria’s diverse communities. In many rural clinics, electricity is unreliable and limited internet coverage according to the National Bureau of Statistics, making it difficult for health workers to log cases consistently and in real time.

This disproportionately affects Nigeria’s rural populations. Even when connectivity is available, some health workers lack the digital skills or confidence to use such tools effectively. Outbreak alerts sent via text message frequently fail to reach the people who need them most, especially in households where literacy is low or women do not own personal mobile phones.

According to UNICEF , female literacy rates in the North-East and North-West remain particularly low with fewer than four in ten women literate, compared to nine in 10 in the southern zones. This is well below the national average, which has ranged between 59% and 61% in recent years, depending on the age group and survey methodology. Such disparities weaken the effectiveness of text-based health alerts, which are often delivered in English and therefore inaccessible to many women in these regions.

For some communities, digital reporting can also provoke suspicion, raising questions about how information will be used and whether sharing data might lead to unintended consequences.

Lessons from across Africa

Nigeria is not alone in facing this digital readiness gap. Across Africa, countries are testing approaches that adapt technology to the realities of their populations. In Kenya, solar-powered “talking books” have increased timely disease reporting by more than 30%, reaching communities where literacy is low.

Ghana’s DHIMS2 integrates facility-based reporting with community surveillance, offering a model of data flow that connects the grassroots to the national level. Africa CDC’s Digital Disease Surveillance and Cross-Border Surveillance programme, supported via digital dashboards and mobile interfaces, also show how mobile data, event management, and cross-border linkage can be harnessed to strengthen continental outbreak tracking.

These examples reveal an important truth; technology reaches its fullest potential when it is designed around the realities of the people it aims to serve. Tools that are adaptable, inclusive, and user-friendly are more likely to succeed than those that assume uniform levels of literacy, connectivity, and trust.

Bridging the gap with human-centered solutions

For Nigeria, bridging this readiness gap means investing not only in platforms but also in people. Surveillance systems must be accessible in local languages and voice-enabled for users with low literacy. Offline-compatible tools can ensure functionality in communities with poor connectivity. Continuous digital literacy training for health workers, from community volunteers to clinicians, is essential to boost confidence and consistency.

Hybrid communication strategies that combine SMS alerts with trusted channels such as radio broadcasts, community health workers, and local leaders can ensure messages reach every household. Perhaps most importantly, deliberate community engagement is needed to build trust in digital surveillance, dispel misinformation, and make citizens partners in epidemic preparedness rather than passive recipients.

Nigeria’s epidemic surveillance systems represent an important step toward stronger health security and universal health coverage (UHC). But without parallel investments in infrastructure, literacy, and trust, even the most advanced tools risk being underutilised. Resilience in the face of future outbreaks will not come from technology alone. It will come from communities empowered to act, health workers equipped to respond, and systems designed with inclusion at their heart.

SORMAS and other digital platforms hold immense promise for Nigeria’s public health future. The challenge and the opportunity lie in ensuring that every innovation is matched by the human capacity to make it work.