Sharon Atieno (Lead writer)

According to the 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), the use of modern contraceptive methods among married women increased from 53% in 2014 to 57% in 2022. Despite national increases, uptake remains low among the Kenyan Somali population, a group that makes up 4% of the national population.

The survey also revealed that counties with a high population of Kenyan Somali women have the lowest uptake of modern contraceptives. These include Mandera at 2%, Wajir at 3%, Marsabit at 6%, and Garissa at 11%.

Ahmed Fatuma, a community health promoter (CHP) in Eastleigh, Nairobi, explained that many of the women do not use contraceptives because of religious and cultural beliefs. “They believe that having as many children as one can is a blessing,” she said, adding that some believe that contraceptive use causes infertility.

Husbands also place an added barrier. “They believe that if women are not giving birth, then they have no use in the home,” Fatuma explained. Additionally, there are many myths and misconceptions surrounding contraceptive use within the community. Besides claims of barrenness, some say it can lead to weight gain or loss, which discourages uptake within the community.

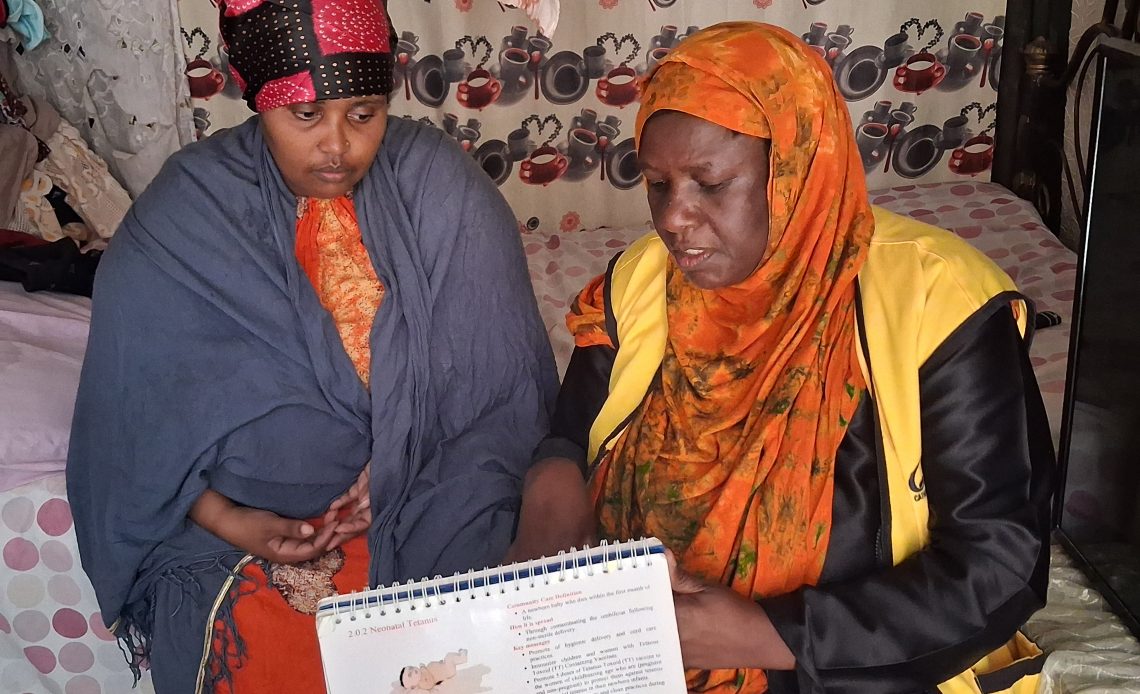

Community Health Promoters (CHPs), previously known as community health volunteers (CHVs), are trained community members who deliver primary healthcare directly at the household level, serving as the first link between families and health facilities. They are selected in a public baraza, Swahili for “village gatherings”, where community members play a central role.

Some members are also identified by Chiefs and community leaders based on their influence and respect within the community, and their willingness to serve the community. Once identified, the individual is put forward and presented to the Community Health Assistant (CHA), who provides supervision, but final approval must still come from community members during the baraza.

Fatuma explained that CHPs receive an average monthly stipend of 5,000 Kenyan Shillings (KSh), (about US$ 50) funded through a co-financing arrangement between the national and county governments. They work within community health units that each serve roughly 5,000 people. Every unit has one CHA who supervises 10 CHPs, and each CHP is responsible for approximately 100 households.

A survey shows a bit of progress

A household survey conducted between April and November 2021 found a gradual, but notable shift in contraceptive use within the Kenyan Somali community. Among the 415 married refugee women and 523 non-refugee Somali women aged 15 to 39 who were surveyed, the overall modern contraceptive rate (mCPR) was 34%. Uptake of contraceptives was also relatively higher among non-refugees at 43%, compared with 24% among refugees, with the primary methods of contraception being injectables, implants, oral contraceptive pills, and male condoms.

According to recommendations by Dr Eliphas Gitonga, the survey researcher and Population and Sexual Reproductive Health expert, women should be targeted with the correct information about contraceptives to ensure uptake is higher. “Many women would love to do family planning, but they need the right information that is able to debunk the myths they have heard about family planning,” he explained.

“Men should be engaged both as users and decision-makers,” said Dr Eliphas Gitonga. “If male outreach is conducted by trusted people from within the community, acceptance is higher; Somali communities tend to place greater trust in their own.”

It is against this background that CHPs like Fatuma are helping shift perceptions among Kenyan Somali women regarding the use of contraceptives. As a Kenyan Somali woman herself, she understands the traditions, sensitivities and spiritual beliefs that influence the community’s views on modern healthcare.

Currently, there are over 100,000 CHPs in the country, distributed across the 47 counties based on the population and geographical characteristics. Fatuma noted that their work involves going door-to-door visiting households to deliver key health messages on health promotion and disease prevention.

CHPs identify common signs and symptoms, provide health information and advice, manage minor illnesses, such as diarrhoea, with support from the CHA, and refer cases beyond their scope to health facilities.

Their work also involves engaging community members especially, women, sensitising them on the importance of contraception and what benefit it has to them and their families.

“I go to their houses, and I talk to them. Some are welcoming, some are not. But I am very persistent. I give them the information then tell them to think about it. I go back the next day to find out if they made up their minds about it or not,” Fatuma noted. For those that agree, she takes them to the health facility where they get the contraceptives. “Others do not want to listen and may even chase you away,” she said.

Fatuma described a case she encountered of a woman who during childbirth. She already had eight children and died giving birth to the ninth child. She used the example to highlight the risks of high-parity births. “It’s so sad that she didn’t get to live to raise her son,” she said.

Using support groups to raise awareness

According to Aisha Hamisi, another CHP in Eastleigh, her approach involves using the Qur’an to help community members understand the importance of family planning, given that the community is predominantly Muslim.

Image Credit: Nigeria Health Watch

They have also established support groups within their units, each comprising 20 members. These groups are mainly formed for women who struggle with clinic visits and who have a child under five or are currently pregnant. The women receive training, and they form neighbour groups for other community members.

Once their children reach five years of age and they are no longer pregnant, they transition out of the group. The CHPs use materials such as the mother and child booklet provided during antenatal care, in addition to other teaching aids.

Now, Hamisi has five support groups, four with all women and one is made up of men only. “We have noticed that men play a key role in the decisions that women make in the Somali community. We must include them so that they can help us to spread the message in their homes and among their peers,” Hamisi noted.

She meets each support group once a month to share information on key health issues, including antenatal care, family planning, and vaccination. She also participates in their WhatsApp groups, where she responds to their questions.

According to Bajo Abdulkadir, a 32-year-old mother of four from Eastleigh, her youngest child is only six months old, yet she has already opted for a three-year implant to prevent another pregnancy. “I thank Hamisi and the support group for helping me to get the correct information about contraceptives. I really didn’t have the correct knowledge; however, I have been taught about contraceptives and even reporting in case of any undesirable side effect,” Bajo said.

Stockouts pose a challenge

Despite the rise in uptake, challenges remain. Hamisi noted that stockouts are common and can last for months. “Most of our clients love the injectable three-month contraceptive. However, sometimes it is not available, and they are told to either take another option or buy from a chemist where they are expensive,” she explained. She added that they are currently experiencing a stock out of daily pills, which has lasted nearly six months.

In Kenya, the Ministry of Health through the Reproductive and Maternal Health Unit (RHMSU) quantifies needs, secures funding, and oversees procurement of family planning commodities. Government procurement of these commodities is primarily carried out through KEMSA, based on the national plan and available funds. Development partners also procure commodities through their own international systems and supply them either as donations or through specific co-financing agreements.

The length of the procurement process for new goods varies significantly, and, in many cases, may take more than one year from start to finish.

In addition, language barrier in the health facilities sometimes hinders women especially refugees from accessing contraceptives. Some women speak only Somali and some of the health workers in the area may come from different communities across Kenya.

For those who cannot speak Kiswahili or English, they need an interpreter who might not be readily available. The CHPs sometimes improvise by looking for someone within the facility who can speak Somali so that they can interpret.

Across several African countries, communities are increasingly engaging local members as advocates for sexual and reproductive health and rights. In Nigeria, Lafiya Sister, an initiative of Lafiya Nigeria, and MS Ladies, an initiative of Marie Stopes Reproductive Choices, are helping to educate hard-to-reach women and girls about contraception and provide services for those who need them.

Despite persistent barriers from entrenched cultural beliefs to chronic commodity stockouts, the experience of Kenyan Somali women in Eastleigh demonstrates the power of community-embedded solutions. CHPs like Fatuma and Hamisi are not only correcting misinformation; they are reframing contraceptive use in ways that respect faith, affirm women’s autonomy, and centre the realities of a community often overlooked in national public health conversations.

As similar community-driven initiatives emerge across Africa, the Kenyan experience offers an instructive model: when health systems recognise the influence of local actors and empower them with the tools they need, even the most sensitive behaviours can shift. For women like Bajo Abdulkadir, whose choices are now informed and supported, these shifts translate into healthier families and futures built on agency, not fear.