From the moment the novel coronavirus was identified in January 2020 and subsequently declared a pandemic in March, the race has been on to control the outbreak. Governments around the world locked down their countries and advised on tough public health and social measures for self-protection and to protect loved ones, as well as to limit the spread of the virus. These all came at a great economic cost.

The spread of the virus was unprecedented and emergency healthcare services became overwhelmed. There was an urgent need to find a medical intervention to stem the spread of COVID-19 and to hopefully put an end to the pandemic. The scientific community came together, sharing data to fight the spread of the virus. It became clear that vaccines were our best bet to restore our lives back to what we all previously knew.

No other medical intervention in the history of public health has saved more lives and enabled the eradication of an infectious disease. The race for a vaccine was on!

The vaccine roll-out

Vaccines took centre-stage in the response, mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines won Emergency Use Listing (EUL) in November 2020, offering a lot of hope and excitement on the potential that science offered. Countries made orders.

With the rapid evolution of the pandemic, two years later, we have witnessed an unpredictable and unparalleled response to the vaccine rollout. While vaccines have not fulfilled some of the initial promises of reducing the burden of infections, they have reduced the number of severe cases and deaths. Now, many countries in the West are pushing hard on their roll-out of booster shots. In Nigeria, we are struggling to get vaccines out, with variable performance by states.

From this, many lessons can be learnt in Nigeria.

(i) Strengthening vaccine production capacity in Africa — An initiative, COVAX, led by GAVI, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the World Health Organization (WHO) was set up to drive the development and manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines and to ensure equitable access for low-income countries.

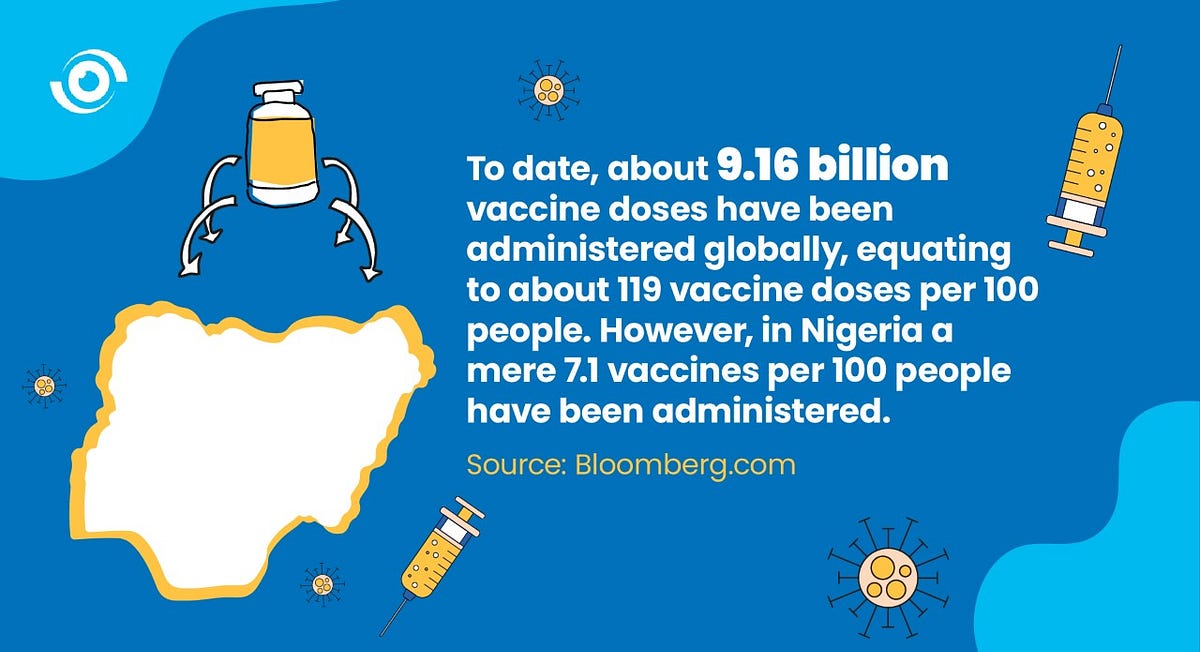

Despite rhetoric about #solidarity and #VaccinesForAll, the #VaccineInequity that transpired was déjà vu. High-income countries struck bilateral deals with pharmaceutical manufacturers, purchasing more vaccines than their populations could use. To date, about 9.16 billion vaccine doses have been administered globally, equating to about 119 vaccine doses per 100 people. However, in Nigeria, a mere 7.1 vaccine doses per 100 people have been administered. While there was an intent to ensure that all countries had a fair chance at bringing an end to the outbreak, low-income countries were left behind again, as had happened during previous outbreaks.

The vaccine inequity in the world has been a wake-up call for African countries. Pushing for greater collaborative action to secure the health security of African countries, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention launched the Africa Union/African Vaccine Acquisition Trust (AVAT) which pooled the purchasing power of AU Member States to purchase COVID-19 vaccines. An even more progressive initiative, the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) aims to increase the capacity of African countries to manufacture vaccines.

According to Rwandan President, Paul Kagame, “Because of this terrible pandemic, an opportunity has been created to fundamentally change the pharmaceutical production landscape on our continent”.

During the Special Session of the National Council on Health in December 2021, high-level policymakers discussed how Nigeria could accelerate the local manufacturing of vaccines.

(ii) Encouraging the uptake of vaccines — Following the initial roll-out of vaccines in high-income countries, the first vaccines were delivered to Nigeria via the COVAX facility in March 2021 and the vaccination programme started in Nigeria. In parallel, the onslaught of misinformation that had started with the onset of the pandemic, continued and disrupted the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine. This challenge was not unique to Nigeria and it highlighted the importance of developing a good understanding of the resistance to the vaccine and the development of clear communications about the vaccine.

In order to ensure the rapid distribution of vaccines in countries like South Africa, the government leveraged on technology by developing an online portal to track recipients and to send out reminders, which was very quickly adapted into local languages to educate local communities.

The Nigeria government appeared to focus primarily on enlisting religious leaders and other trusted community members to encourage uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine. This strategy had worked well during polio elimination efforts.

There were teething problems with the technology deployed during the roll-out, that seemed to discourage uptake. These issues are being addressed and uptake is increasing, but too slowly in some states. This is worrying as variants of concern, like Delta and Omicron have emerged, as booster doses are now being administered, while many Nigerians remain unvaccinated. Having prominent leaders who tested positive share real-life experiences should help dispel any myths that COVID-19 is not still a threat

What now in 2022?

Top of the list of priorities for 2022, will be the need to re-think how pandemics are prevented and responded to globally. Global “solidarity” will not happen on its own, as evidence has shown that most countries act to protect their own perceived best interest. During the special session at the World Health Assembly in December 2021, there was a consensus to intensify epidemic preparedness and response and strengthen the global health architecture through a new legal instrument that will define the responsibilities of countries to act.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General stated, “The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the many flaws in the global system to protect people from pandemics: the most vulnerable people going without vaccines; health workers without needed equipment to perform their life-saving work; and ‘me-first’ approaches that stymie the global solidarity needed to deal with a global threat”.

So, in 2022, the world needs to move towards greater equity access to life-saving therapeutics, diagnostics and vaccines in response to the pandemic. We are all in this together.