By Thelma Chioma Abeku and Ikemefuna Igwe (Lead Writers)

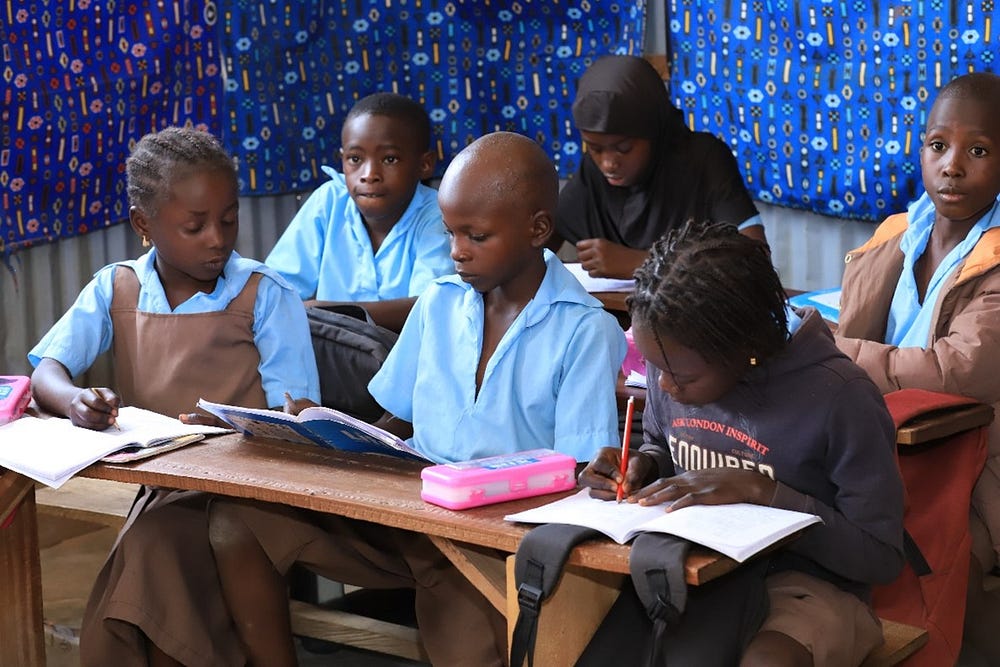

At first glance, the buildings that house the classrooms of the Transitional Learning Centre, Wassa, appear to have been designed to blend them into the brown sun scorched terrain that surrounds the centre. However, the classrooms themselves were anything but ordinary, as the Nigeria Health Watch Team discovered when they walked into the first classroom to find it beautifully decorated with colourful ankara fabric.

The five-classroom building located in Wassa community in Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT) was constructed with support from the National Refugee Commission, Migrant and Internally Displaced Persons and currently houses one hundred pupils. The majority of them are children whose parents fled the insurgency in the northeast of the country and are seeking refuge in the Wassa internally displaced persons (IDP) camp.

The Transitional Learning Centre was established in 2019 when Maple Leaf Early Years Foundation (MLEYF) set up a learning centre in Gwarinpa and began providing 50 children, from ages 4 to 14, in the Durumi IDP Camp with free education, school supplies and one meal per day to encourage school attendance and address malnutrition. The children were transported from the IDP Camp to the MLEYF Centre in Gwarinpa, daily. The organisation’s mission was “to provide basic education in emergencies for displaced children from low-income families, rural areas, underserved settlements, and children affected by tragedies such as war,” according to Ifedinma Nwigwe, Executive Director, (MLEYF)

Designed to help meet the learning needs of displaced children and recognising that IDP camps are transient, as the name implies, the centre is designed as a semi-permanent structure that can be moved to a different location, when the need arises.

More children were enrolled in the programme and the space at the MLEYF Center in Gwarimpa quickly became too small. This prompted the need to move to a location with sufficient space to build and expand. In 2022, with some assistance from the government, they moved to their current location in Wassa.

According to the World Food Programme , hunger affects a child’s ability to concentrate and even assimilate what is being taught in school, therefore, implementing a school feeding programme promotes better health and allows children to learn and perform better. As a result, the Federal Government launched the Home-Grown School Feeding Programme (HGSFP) to improve the nutrition, health and educational outcomes of public primary school students. Currently, over nine million pupils from 54,619 schools have benefited from the programme.

“When we brought the children to our centre we gave them milk, lunch and an afternoon snack and we noticed a change in their appearance and in their behaviour after a week of feeding them properly,” Nwigwe said recalling how frail the children were when they first arrived.

To ensure that the children were fed a balanced diet, the MLEYF worked with a nutritionist who developed a food schedule that included all classes of food. Every week, from Monday to Friday, the children are fed rice, beans, yam, eggs, fish, and vegetables. According to Nwigwe, it costs 100 naira to feed one child every day. Taking advantage of their location in a rural community the Foundation obtains some of the raw foods at a highly reduced cost. In addition, they decided to convert some of the land they acquired to be used for an ‘Agri-vocational programme’, which works with unemployed young adults in the community to grow cash crops, grains, and vegetables for the school feeding programme. They also make sure to include foods that are in season on the food menu, because they can be procured at a relatively cheaper cost.

Another strategy MLEYF employs to manage costs while also ensuring that the quality of food served to the pupils is not compromised involved taking a daily roll call before preparing the day’s meal. This is especially effective because it helps the school’s cook and the volunteer who assists her, both of whom are community members, to plan better and ultimately, reduce food waste.

Nwigwe revealed that the initial funding to start the programme came from personal savings as well as donations from friends and family members. Hoping to get additional support from the government, particularly as the Transitional Learning Centre feeding programme is similar to the HGSFP, Nwigwe said she reached out to relevant officials and found out that although the HGSFP is designed to improve the nutrition, health and educational outcomes of public primary school students, the programme does not yet include displaced children.

As a result, family, friends and partners continue to be the centre’s primary source of funding. “As of today, we have more donations from family and friends including our partners who see value in the work that we do as well as being accountable for every donation received,” Nwigwe said.

According to Nwigwe, the fact that the children arrive in school eager to learn and are visibly nourished by the meals and snacks provided at the centre is evidence of the significant impact of the intervention on the lives of the pupils as well as their parents. However, because it requires funding to sustain a project like the Transitional Learning Centre, she is always on the lookout for potential funding sources.

“Looking for funding is a continuous process because there is always something to do. With more funding, the goal is to ensure that more children are able to benefit from the programme,” she said adding that “The vision for the future is that every child regardless of their social status has access to quality education and one square meal in school.” Seventy percent of the children enrolled in the school are from the IDP community, while 30% are from the Wassa community.

According to a 2022 report from the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Nigeria has an estimated 19.7million out-of-school children; ranking third highest globally, after India and Pakistan. This figure, which is 2.1 million higher than the estimated population of densely populated Lagos State, is more than a statistic because it represents every child of primary and secondary school age in Nigeria, who does not have access to any form of formal education.

The large number of out-of-school children is as a result of the triple threat of poverty, insecurity and access, particularly for the families displaced by the Boko Haram insurgency. As a result, the HGSFP should be expanded to ensure that children like Juliana Simon, a primary 4 pupil whose parents lost everything when they fled the insurgency, can benefit from it.

Home Grown School Feeding programmes can potentially make a significant contribution to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 2 on ending hunger, achieving food security and improved nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture, as well as SDG 4 on ensuring quality education.

With increased and sustained funding and strategic resource investment, many more children can benefit from the Transitional Learning programme. The federal government should, as a matter of urgency, include children from the Wassa Transitional Learning Center, as well as other displaced children from across the country, in the HGSFP. School feeding programmes have been shown to increase school attendance. To address the growing challenge of out-of-school children and the poor nutritional status of many children, interventions such as school feeding programmes that also allow children to eat a more diverse diet would help solve a vexing problem.