By Atinuke Akande-Alegbe and Dara Ajala-Damisa (Lead Writers)

As part of efforts to improve Nigeria’s nutrition statistics, a National Strategic Plan of Action for Nutrition (NSPAN) was devised for implementation between 2014 and 2019. It is a follow-on to other strategic documents including Vision 20:2020 and the National Strategic Health Development Plan for 2009 to 2015. The plan provides guidance and motivation to the different levels of government to develop more in-depth implementation plans for nutrition interventions in Nigeria.

The goal of NSPAN is to build upon the framework outlined in the National Food and Nutrition Policy to improve the nutritional status throughout the lifespan of Nigerians.

The timeline for the National Strategic Plan of Action for Nutrition wound up in 2019. Nigeria Health Watch in partnership with Alive and Thrive reviewed critical aspects of its implementation in this year’s nutrition policy dialogue, which held on June 16, 2020.

Speakers at the webinar included Dr. Chris Osa Isokpunwu, Senior Technical Assistant to the Honourable Minister of Health, Head of Nutrition Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria; Ngozi S. Onuora, Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Rivers Field Office and Ibiso Ivy King-Harry, Nigeria Coordinator (Acting), Scaling Up Nutrition Business Network (SBN).

The speakers provided insights on three key themes: The development and implementation of the NSPAN, roles of different stakeholders and the impact of COVID-19 on nutrition.

Implementation of the National Strategic Plan of Action for Nutrition

Webinar Moderator and Managing Director of Nigeria Health Watch, Vivianne Ihekweazu, highlighted the overall goal of the NSPAN, which was to improve the nutritional status of Nigerians with deliberate and special focus on vulnerable groups such as women of reproductive age and children under-five.

Victor Ogbodo, Project Director of Alive and Thrive, in his opening remarks said, “Five years ago when the NSPAN was presented, there lots of expectations. A lot of work has gone into it the plan and awareness of nutrition issues have been placed closer to the front burner”.

Dr Chris Isokpunwu, who was at the forefront of the development and implementation of the NSPAN shared reasons for its development and the challenges the government faced in its implementation. He explained that nutrition in Nigeria was largely underfunded until 2011 when Nigeria joined the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement. This brought together partners and policymakers with a common goal, Isokpunwu said. “The first step for the power partnership between the government, policymakers, donors and community members was to develop a plan that drew a map for the goals and aspirations of the group’s nutrition vision for Nigeria,” he added.

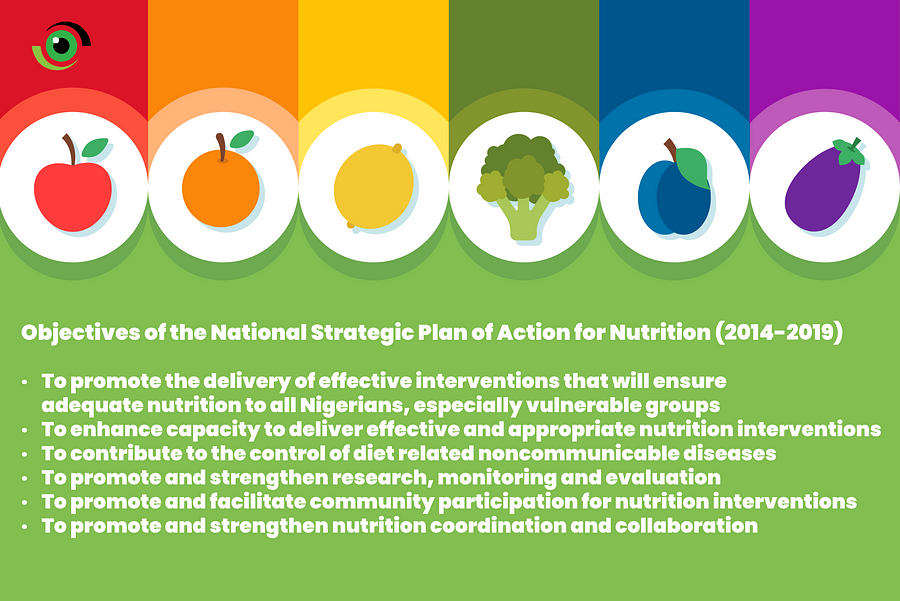

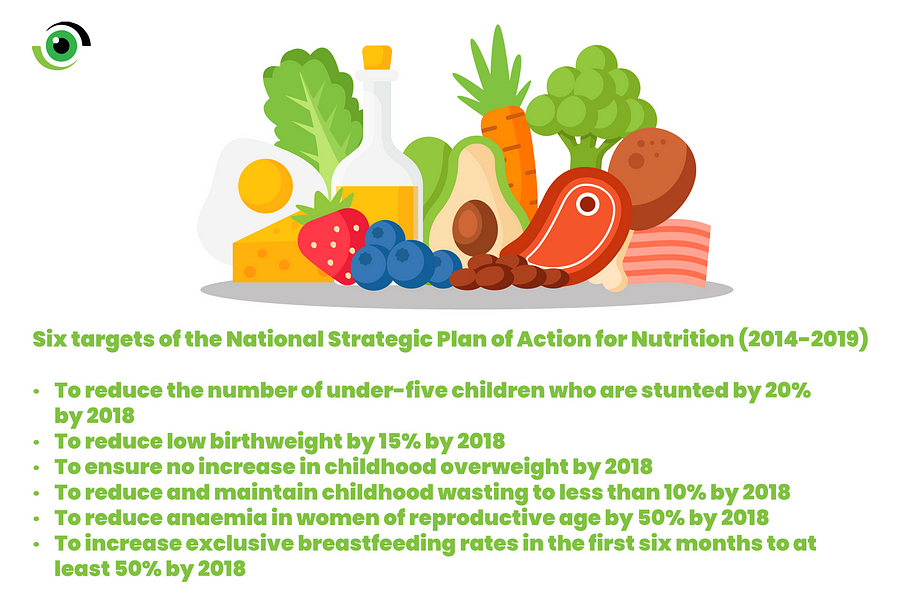

Dr Isokpunwu said he usually referred to the NSPAN as a plan of 6; with 6 targets, 6 objectives, 6 strategies and 6 priority areas. He stated that it was challenging to agree on priority areas for the plan because of competing needs of stakeholders.

Although the NSPAN became multisectoral, going beyond the health sector with agriculture, budget and national planning sectors taking lead roles, coordination was a huge challenge and it still is, he said. Yet, the plan was well-received and publicised, and Nigeria was one of the first countries among the SUN movement to develop such a nutrition plan, he said.

Ibiso Ivy King-Harry explained that the development of the NSPAN went through extensive consultations to ensure all stakeholders were on board, especially at subnational levels. At the end of the development process, all stakeholders looked forward to its implementation because everyone could identify with it, she said, adding that the plan had some limitations in the overall implementation because not enough states that domesticated and properly implemented the NSPAN.

She said not enough funds have been budgeted for nutrition activities and when they were budgeted, these funds were not always disbursed as expected. Overall, she believes that the NSPAN is a comprehensive program regarding the health system’s response. However, she cautioned that health systems should only complement nutrition programs and not deliver them wholly.

Ngozi S. Onuora, Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Rivers Field Office believes that the NSPAN contributed fairly to the gradual improvement in Nigeria’s nutrition indices. She compared the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) figures of 2013 and 2018 against the targets of the NSPAN and used it to measure the impact of the plan. Based on the 2018 NDHS, some indices such as stunting levels, reduction in low-birth weight, and reduction in anaemia among women of child-bearing age in Nigeria remained the same even with the implementation of the NSPAN. However, Onuora stated that wasting levels drastically reduced from 18% in 2013 to 7% in 2018, thus meeting the NSPAN’s target of reducing and maintaining wasting to below 10%. Some progress can also be attributed to NSPAN in the area of exclusive breastfeeding, which stood at 17% in 2013 increased to 29% in the 2018 NDHS.

She argued that as the only working document that bound nutrition stakeholders together since 2015, the NSPAN has contributed to behavioural change, and increased political will and awareness for nutrition in Nigeria. She believes that all these would help with the campaign to increase funding and resource mobilisation for nutrition.

The importance of partnerships for better nutrition

For any plan to be impactful, a strong multi-sectoral component must be in place from inception. Speakers at Nigeria Health Watch and Alive and Thrive’s Nutrition Webinar reflected on government’s collaboration with the private sector and NGOs in implementating the NSPAN, especially at the state level. Dr Isokpunwu highlighted that before the NSPAN, “Businesses did not think they had any role to play in nutrition, we had only businesses involved in food fortification. Over time, different businesses from small and medium scale food processors to banking industries have joined in promoting good nutrition.”

He emphasised that there was previously mistrust between the industries and government, stating how they had to deal with issues relating to the Breast Milk Substitute Code where some infant formula manufacturers disobeyed the code. In all, he said that the NSPAN provided a platform for engagement for progress where the government has shown commitment by increasing resources for nutrition, extending partnerships to industries, and creating an enabling environment for the participation of the private sector.

King-Harry believes that these partnerships are vital and during the implementation of the plan, it strengthened Nigeria’s nutrition indices even with traditional leaders, as well as partnerships with food and beverage manufacturers and policymakers.

In Nigeria, UNICEF has increasingly focused on strengthening policies, government systems and accountability to ensure adequate financing of nutrition. “UNICEF was at the core of partnerships in the development of the NSPAN in provision of funds and technical support,” Onuora said. Funding was a major challenge in the implementation of the NSPAN. She explained how UNICEF leveraged on legislative and executive arms of government, including The Nigeria Governors Forum, to improve awareness and advocacy for better funding for nutrition.

Impact of COVID-19 on Nutrition in Nigeria

The United Nations World Food Program cautioned that the number of people facing food insecurity may double by the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clearly, the movement restrictions imposed to control the spread of COVID-19 is taking a toll on the Nigerian food system. Isokpunwu agreed, saying that the impact is felt at the individual, community and public health level.

He pointed out that the Federal Ministry of Health and some partners developed the Nigeria Food and Nutrition Response Plan for COVID-19. The objective of the plan is to ensure the integration of nutrition into the national COVID -19 response plan and emphasize the importance of good nutrition in supporting the immune system. “The plan also aims to prevent a worsening of the nutrition situation of the vulnerable populations in Nigeria. In developing the plan, we prioritized behavioral change communication continuity of nutrition interventions, ensuring food security and access to nutritious food remains open,” he said.

The private sector, NGOs and philanthropists, are supporting the COVID-19 response by donating food items. Considering that some of these foods may not be nutritious, it is important to have guidelines on what types of food should be donated.

“The COVID-19 nutrition plan included the development of a minimum package for food groups that government and partners can use for palliatives, supporting the distribution of nutritious food baskets and promoting the inclusion of animal source proteins in food distribution for vulnerable groups. However, if we had put together these guidelines earlier, it would have gone a long way in shaping the types of food that are provided to people,” King-Harry said.

Ihekweazu added that, “We also need to consider using social media to put out messages to people on the types of nutritious food they should eat, especially now. We need to educate Nigerians on the locally available foods that are nutritious.”

Speaking on the impact of COVID-19, Onuora explained that the pandemic has impacted the food value chain, ranging from large scale farming to individual’s nutritional options. At the onset of the pandemic, UNICEF identified the possible immediate, short and long term impacts of COVID-19, she said. Across the country, several nutrition interventions have faced challenges since the COVID-19 pandemic, Onuora said. “For UNICEF, restricted access to health services, especially during the first lockdown, was a huge bottleneck for the implementation of some of our programs. For instance, many women were unable to attend antenatal classes where they learn infant and young child feeding practices such as exclusive breastfeeding,” she added.

While there have been some improvements in Nigeria’s nutrition statistics since the implementation of the NSPAN, malnutrition remains a direct or underlying cause of 45% of all deaths of under-five children. Nigeria’s progress on malnutrition is slow especially in meeting the global targets.

Nigeria is not on track to meet the 2025 global nutrition targets. What would you suggest be included or removed in the second NSPAN? How would you score the success of the NPSAN? What strategies would you suggest should be adopted to improve Nigeria’s nutrition outcomes? Share your comments below.

A good step and a good effort all to improve nutrition. Thanks dearly