Listen to the story below

By Innocent Eteng (Lead Writer)

It is 8 am and a dark cloud of haze has darkened the Port Harcourt skyline making visibility difficult. In Oyigbo, a local government area (LGA) 30 kilometres east of the city, Adanmma Rufus, a receptionist at Richardson Hotel, is checking this writer into room 311. There are spots of a black powdery substance called ‘black soot’, on the bedsheet. Rufus wipes her palm across the sheet in an attempt to brush them off. “Just two days we couldn’t lodge a guest in this room; look, everything here is turning black,” she complained.

The soot-like particles started falling from the skies of Port Harcourt and other parts of Rivers State in September 2016, penetrating lungs, coating surfaces and filtering into enclosed spaces. According to a task force set up by the Rivers State government to investigate and recommend solutions to the environmental challenge, it may be caused by increased levels of illegal refining of stolen crude, decades of gas flaring by oil corporations, burning of tyres for roasting meat in abattoirs and during celebrations, and emissions from asphalt plants. These activities have, for an undetermined period, sent clouds of thick toxic smoke in gaseous form into the atmosphere and now, they are descending because they have reached overwhelming levels.

“Every atmospheric system has its threshold of tolerance…[for] managing our air pollution. This thing (soot) becomes very prominent when it has overcome the carrying capacity the atmospheric system can diffuse,” said Professor Prince Mmom, an environmental and disaster risk management expert at the University of Port Harcourt.

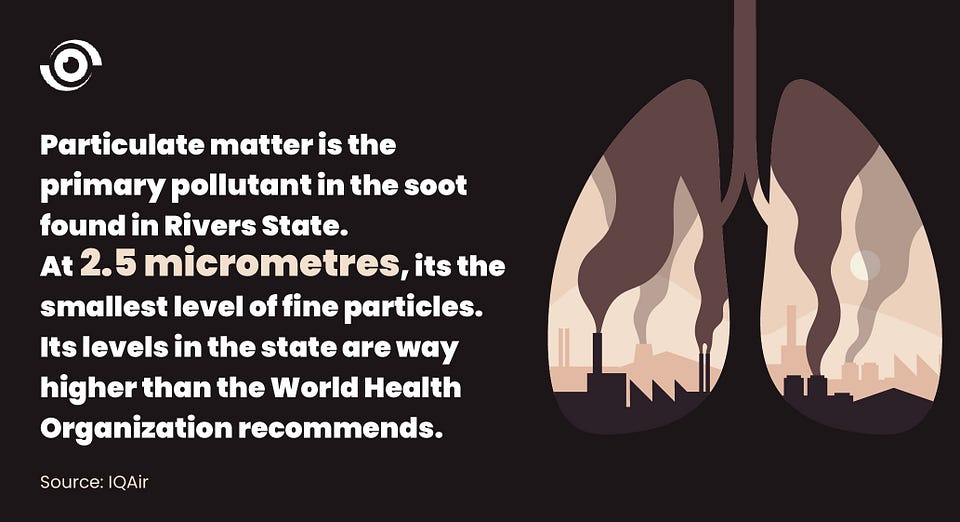

Fine particles kill seven million people globally every year, and 50% of pneumonia-related deaths among under-five kids is due to air contamination. The main pollutant in Rivers State is a dangerous one called particulate matter (PM) 2.5. It is the smallest level of fine particles, as tiny as 2.5 micrometres. Its concentration in the state is 47.6 µg/m³, significantly higher than the 10 µg/m³ the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends. These tiny particles can enter the bloodstream through the lungs by inhalation, the eyes, and through contaminated food and water. Experts say that they can cause heart diseases, strokes, cancers, premature birth, miscarriages, male infertility, and acute respiratory infection (ARI).

In Port Harcourt, residents are experiencing health problems that could be attributed to atmospheric conditions. A 2017 study revealed that ARI among under-5 kids jumped by nearly 20% between 2016 and 2017 and local doctors say they now see patients with soot-related health conditions more frequently than pre-soot times. “There has been a tremendous increase in asthmatic attacks — not only in the number of attacks, but in the frequency. Those that had one attack in two or three months before are now having multiple attacks in a week because of the air pollution in the atmosphere,” said Briggs Bieye, an environmental advocate and public health physician at the hospital wing of the Ignatius Ajuru University in Port Harcourt. He added that sudden infant death syndrome is also rising. “[For] a pregnant woman who smokes, her child is five times at risk of dying during infancy. Imagine pregnant women in Port Harcourt who ‘smoke’ the soot every second for the nine months that they are pregnant. Children die, and they [mothers] do not even know that it is caused by the soot.”

Stop the soot

Of the many identified causative factors of the soot, gas flaring and illegal oil refining top the list. Hundreds of artisanal refining sites dot the bushes of Rivers State, and one LGA alone is said to have about 112 sites. Rivers State has 23 LGAs.

In 2017, the state government banned the burning of tyres and shut down asphalt plants. But because it failed to act on artisanal refining, the pollution continued unaffected. Local activists like Eugene Abels, coordinator of #Stopthesoot, a group campaigning for a pollution-free Port Harcourt said the government seemed reluctant to tackle illegal refineries and stop oil companies from flaring gas. In April 2018, #Stopthesoot led over 5000 residents in a protest march in Port Harcourt, demanding immediate policy action.

About 420 activists signed and sent a petition to the WHO and the United Nations (UN) asking them to intervene. Abels also took the federal and state governments to court, requesting the Federal High Court in Port Harcourt to order governments to use their powers and end the pollution immediately. None of these actions have yielded a meaningful result.

Behaviour change sparks hope

But a flicker of hope rose in Port Harcourt and residents attributed it to a solutions-driven “Stop The Soot Conference” organised on December 9, 2021, by the Rotary Club of Port Harcourt Eco. Organisers wanted a multi-stakeholder approach to creating awareness, teaching residents to take personal safety measures, suggesting ways to end the pollution, and hopefully get the government to act. So, they had in attendance, representatives from the government, traditional institutions, civil society groups, student bodies, multinational oil companies, religious bodies, and media groups. Speakers — mostly experts in health and environment — showed, with proof, the short-term (asthmatic attacks, respiratory infections, child pneumonia, and heart conditions) and expected long-term (cancers, infertility, and congenital disabilities) impacts of the soot.

Stakeholders agreed that the government should tackle the problem by engaging with the youths who steal and refine crude, provide environment-friendly refining alternatives like cellular and modular refineries, incorporate illegal refiners into the legal refining process, and regulate their activities. Days and weeks after the conference, organisers and speakers followed up with appearances on radio programmes to further discuss solutions and expand awareness.

Consequently, on January 1, 2022, the state government took decisive action against illegal artisanal refining by working with LGA chairmen, traditional rulers and whistleblowers to identify and destroy dozens of illegal refining facilities across some LGAs. “They really did a good job,” Bieye admits. “From the beginning of January, we saw that there was really a reduction in the level of soot in the atmosphere of Port Harcourt. We could breathe fresh air.”

Short-lived respite

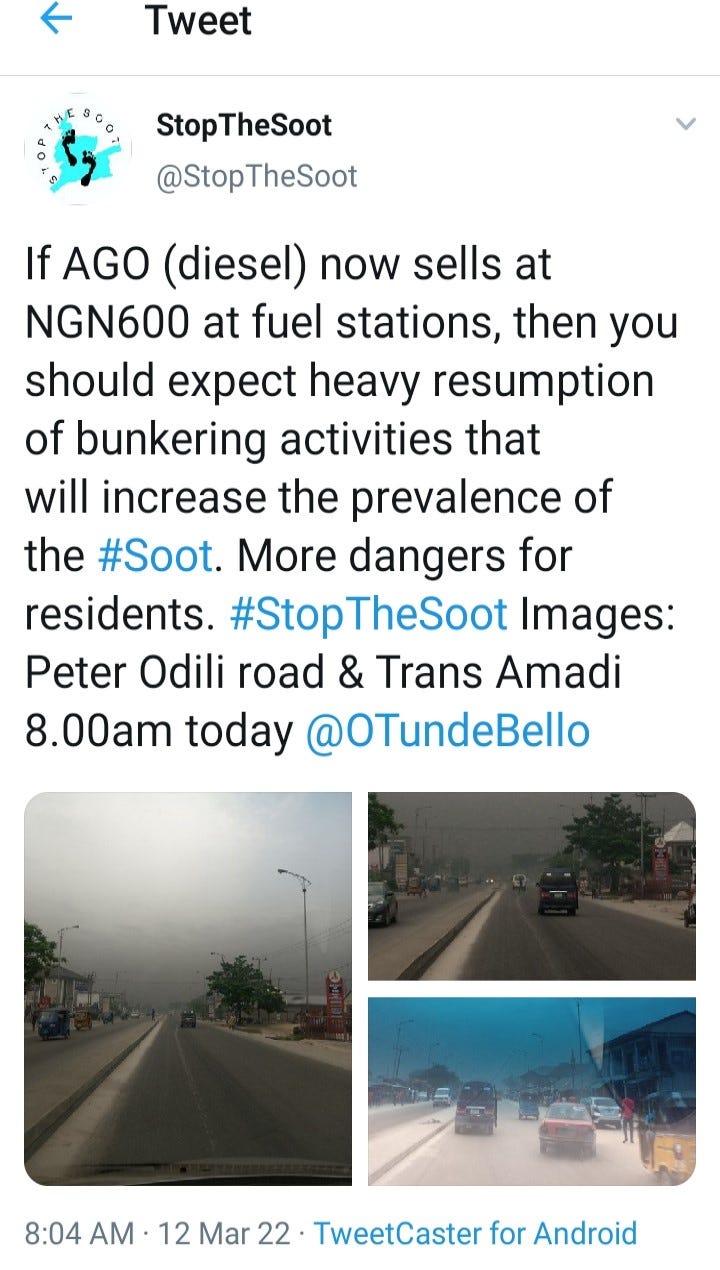

However, the change was short-lived, lasting for just six weeks, because illegal refiners found a way to resume their activities. Activists blame the short-lived success on the government’s not all-involving and unsustainable approach away from recommendations at the conference.

Yet, despite the failure, increased citizen awareness after the conference and possible next steps from the government offer some hope as more people and groups are joining the conversation.

Ilanye Chapp Jumbo, a 54-year-old television presenter with the state-owned Rivers State Television, now boldly uses her time on-air to discuss the soot — something hardly done on state-owned media. “Even if what I am talking about is not about soot, I find a way to chip in soot. I use every platform available to me, including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram,” she said. “I don’t have that luxury to relocate my family. So, if I am determined to stay in my state, and I don’t talk on issues like this, then I am as guilty as those involved in the illegal refining of products.”

Religious groups were not left out. The Health Ministries Department of the Seventh-Day Adventist (SDA) church in Port Harcourt organsed a virtual event between February 12 and 19, 2022. Titled “Soot: A Matter of Life and Breath”, the event featured eight doctors and environmentalists who taught the over 200 attendees (via Zoom and Facebook) measures to tackle the pollution.

“Our [three-hour plus] presentation highlighted that it was not just artisanal refining that contributed to soot. People who use firewood to cook and people who do things that release carbon monoxide into the air [contribute to it]. We wanted them to know that it is not enough to blame. But we can all together solve the problem by intentionally being careful [about] what we do,” Sokiprim Akoko, a clinical and nutritional pharmacologist and director of SDA’s Health Ministries Department in Port Harcourt, said.

As increased and sustained awareness continues, residents are getting better informed about safety recommendations they can observe. Vocal voices like Bieye, Abels, and Jumbo are continually faced with the risk of possible verbal and physical attacks from those who think anti-soot campaigns are an attack on their livelihoods or interests. Yet, they vow to keep talking because lives depend on it. “Why would I not talk when I know that this is the only place I call home?” Jumbo queried.

The soot problem in Port Harcourt has been such a heatbreaking issue for so long. It is such a relief to see that some progress is being made as a result of the active participation of citizens.

It goes to show that there is always a solution, we just have to be willing to pursue it.