The Katsina family of Bida will probably never forget June 20th 2018. Just before 8 p.m. on that day, Mr. Farouk Katsina received an urgent call from his wife asking him to come home. Salihu, their beloved three-year-old son, had been vomiting and stooling uncontrollably. By the time Mr Katsina got home, a neighbour, who is a health worker, had started giving him liquids. Unfortunately, Salihu had already lost so much body fluids that despite the treatment, he died within a few hours.

This is just one of the many heartbreaking stories from the recent cholera outbreak in the densely populated town of Bida in Niger State, a major town connecting Northern and Southern Nigeria. The Katsina family is from the busy Wonigi area, adjacent to the Etsu ‘big’ market in Bida. The area has been reported as the worst hit in the cholera outbreak with three deaths so far. Salihu’s father, Mr Katsina, lives there with his two wives and nine children, in quarters so cramped and unsanitary that outbreaks of infectious diseases like cholera seem inevitable.

According to Mallam Baba Buhari, the Disease Surveillance and Notification Officer (DSNO) for the area, Bida has recorded about 267 cases of cholera from June 3 when the outbreak started, and eight persons have lost their lives. Kyari Ward, which includes Wonigi has had 23 cases, the highest number of confirmed cases in any ward. According to Hajiya Amina M Yahaya, the Director of Primary Healthcare for Bida Local Government Area, this is the first cholera outbreak in the town since 2008, and everyone is asking: why now?

Cholera is mostly spread through contact with faeces-contaminated water. Unhygienic practices like indiscriminate dumping of refuse and open defecation are prevalent in many areas in Nigeria and thus the chances of contact with contaminated water through drinking, cooking, using utensils or eating vegetables washed with contaminated water are high. These practices are common in Bida town, and the constant flow of people travelling through the town meant that the conditions for an outbreak were rapidly met. Most of the cholera cases were brought to Umaru Ndayako General Hospital, a state-owned secondary care centre, and the doctor on duty on the day that we visited, said that in the early days of the outbreak they received over 30 cases a day.

Bida: Transit hub by day, refuse dump by night?

Bida is the second largest city in Niger State with an estimated population of 260,000 people. Its location is peculiar because it lies on the A124 highway connecting the south and the north of Nigeria, thus making it a major transit hub. Two major federal institutions, the Federal Polytechnic and the Federal Medical Centre (FMC) are situated there, and Bida is home to the only Nursing School in Niger State.

Unfortunately, the town is also known for poor public environmental sanitation, making it susceptible to communicable disease outbreaks like cholera. Large amounts of refuse are dumped right in the heart of the communities, next to residential areas. Between the Federal Medical Centre and the School of Nursing a huge refuse dump sits ominously in the midst of houses inhabited by locals, students and staff of the two institutions.

In Wonigi, a refuse dump occupies a large piece of land at the community centre. Sadly, the local children have turned it into a playground. Worse still, the only drainage in the area has been turned into another refuse dump where people often defecate. In the rainy season this toxic waste is washed down directly into the major Langzun River that divides Bida town.

Perhaps the two biggest dumps in the town are in Banwuyia, another densely populated area. Both are as high as the buildings surrounding them and possibly higher. According to Mallam Tauheed, who lives in the area, they have been piling up for more than 20 years and as not much has been done about them, they grow larger every year.

NISEPA: Overwhelmed by the refuse dilemma

The Niger State Environmental Protection Agency (NISEPA) is tasked with regulating and maintaining standard and healthy environmental practices in the state. According to the Agency’s Director General, Engr. Lucky Barau, the Agency has about 2000 staff and only 30 waste disposal trucks to serve the entire state. According to him, the town of Bida should have at least ten trucks to remove refuse but has to make do with only three! This works out as a ratio of one truck to 86,000 people, a grossly inadequate provision. Unless the Agency acquires additional trucks, Engr Barau says, the large refuse dumps in Bida and other towns in the state will remain. “NISEPA collects only about 30% of the waste in the state; the remaining 70% are still out there in the communities, he said, adding that in 2016, Niger State Governor Abubakar Sani-Bello approved the purchase of more trucks, but the funds for those purchases are yet to be released.

A preponderance of environment-related disease outbreaks in Nigeria

Frequent outbreaks of infectious diseases seem to be the norm in Nigeria. Over the past few years, the country has had to contend with quite a number. From the 2012 Lassa Fever outbreak in 19 states, to the deadly Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in 2014 and the 2015 outbreak of Meningitis in the two Northern states of Sokoto and Kebbi.

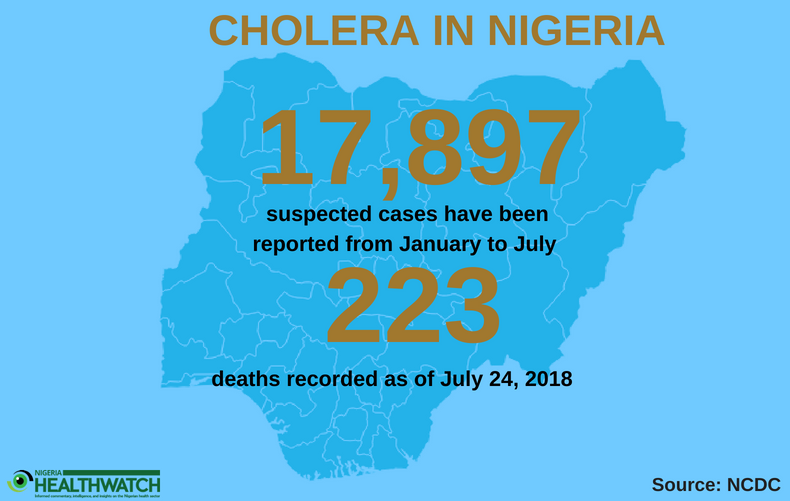

The most recent Cholera outbreak started in Kwara state in June 2017 and spread to 12 states. According to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), 17,897 suspected cases were reported across the country from January to July and 223 deaths had been recorded as of July 24, 2018. The outbreak appears to be predominantly in Northern Nigeria. Some of the worst-hit states are Bauchi with 9331 reported cases, Adamawa with 1718 reported cases and Borno with 1543. These three states are in the North-east, a region still recovering from an almost decade-long insurgency that has led to thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Zamfara State, in the North West, which is currently facing major insecurity challenges from armed bandits has reported 1896 cases so far. Another North-Eastern state, Yobe has reported 449 cases with 17 deaths. Of the six North-Central states, only Benue has not reported a cholera case so far; Anambra and Ebonyi are the only two states to report cases from the Southern part of the country. This demonstrates that the outbreak is largely confined to Nigeria’s Northern states.

Solving the public waste management dilemma: Three approaches

Proper waste management, from dumping to collection and hygienic practices such as using washrooms and toilets, hand washing and community sanitation, are tasks that require everybody’s participation; at individual, community and government levels. All tiers of government must however be responsible to initiate and enforce policies that will keep the environment clean. In light of the current cholera outbreak and the overwhelming task ahead of its’ environmental protection agency, Niger State would do well to pick up ideas from other waste management initiatives in Nigeria and internationally, that seem to be achieving some progress.

The Cleaner Lagos Initiative is one model Niger State should understudy if it is serious about dealing with its waste management dilemma. Lagos State recruited, trained and deployed over 27,000 community sanitation workers to all the 377 wards in the state. Their work does not stop at ‘sensitization’, unlike in some other states, but they are also tasked with leading and taking part in the community sanitation exercises. Lagos State also has over 100,000 waste bins and about 120 private Waste Collection Operators assigned to operate in specific areas. Although there have been some challenges rolling these schemes out, Lagos State seems well on its way to helping its residents maintain a relatively clean and healthy environment.

In Ghana, a clean water and sanitation approach using community volunteers has reduced cholera cases in Cape Coast from 735 in 2016 to a mere nine in 2017. The initiative, coordinated by Global Communities and strongly backed by the Cape Coast mayor, involves home inspection, food vendor inspection and market sanitation. The volunteers are allowed to seize foodstuff and materials that are deemed hazardous. Bida would benefit greatly from an initiative like this. At one of the entrances to Wonigi, for example, kilishi, a popular local dried meat delicacy, is spread openly on tables and roofs where dust, flies and vermin freely perch. This is not peculiar to Wonigi, but is a practice seen in almost every town, most commonly in Northern Nigeria.

Finally, a country-wide example from Eastern Africa is Rwanda’s Umuganda practice, a mandatory, monthly community effort that focuses mainly on sanitation. This is a solution that should be imitated not only by Nigeria but many other African countries. Umuganda, which when translated means “coming together in common purpose to achieve an outcome,” takes place in every neighbourhood. Every household must clean its surroundings and send one adult to participate in cleaning the community. The practice has not only kept the country clean but has also helped in uniting its people after a horrific civil war.

In March 1984 Nigeria instituted the Environmental Sanitation Days on the last Saturday of the month. Between 7am and 10am, movement is restricted and citizens are expected to use the time to clean their environments. However, with time, the practice became patchily observed and an attempt by the Federal Ministry of Environment to reintroduce it in 2016 seems to have faltered when the practice of restricting movement was declared illegal by the Court of Appeal Lagos Division in 2016. Lagos State subsequently cancelled the restriction of movement, citing its economic impact on the nation’s largest urban economy and the vision of a 24 hour Lagos. This drew some criticism.

Also worthy of note is Nigeria’s failure to make progress on delivering sanitation to its citizens. Water Aid cites it “as the third most regressive country in the world on sanitation and only one of a handful of countries around the world where access to basic sanitation is falling rather than rising.” 71 per cent of Nigerians (over 130 million people) lack access to safe, private toilets and over 46 million Nigerians practice open defecation. Solutions have been proposed but are yet to be widely adopted and implemented

Living a healthy life comes with the hard work of community effort and part of that hard work is ensuring our environment remains clean and hygienic thus curbing significantly the spread of infectious diseases. While the government and other institutions have a role to play, individuals and communities do as well. Frequent infectious disease outbreaks such as cholera can only be prevented if healthy environmental practices are initiated, enforced and practiced by all. For Mr. Farouk Katsina, his community’s failure to do this cut short a dream for his family in his son Salihu’s death. “Salihu was very intelligent, whatever you told him he wouldn’t forget…I wanted him to go to school and become a doctor.”

Are there public sanitation initiatives you have heard of that have are recording successes? Share them with us!

Do you know of any unsanitary refuse dumps in your community? Take a photo and tweet it, tag us @nighealthwatch, with the hashtag #NHWTorchlight. Let’s start a conversation!

I wonder why the house to house inspection by LGA environmental officers cannot be resuscitated. Even the fast food outlets are unsupervised. Basic public health practices are ignored at the detriment of the people. No form of regular public health education. Why do we have National Orientation Agency staff at each local government when basic health information supported by enforcement in collaboration with the environmental officers cannot be carried out? We need serious re-orientation as a people.