Four-year-old Terwase is not in school yet, so he often goes with his mother to the market where she has a small trinkets shop. Terwase gets hungry during the day, and the hot and dry Abuja weather makes him cranky. When they make sales, his mother buys him ‘puff puff’ from Mama Ben down the street. That is what he eats all day, but he is grateful. At least he does not have to eat beans and fish or Kunun Gyada (Groundnut gruel or ‘pap’) which Saratu always eats. Saratu’s mother sells food items beside them and Saratu, taller than the other kids her age, always leads the play team. She does not cry often though. Terwase thinks he will cry a lot if he has to take that Kunun Gyada. He hopes his mother saves enough money to buy noodles, he wants to be like that smiling boy he saw on television eating the noodles.

Terwase and Saratu are fictional characters, but this scenario can help paint a picture of the impact of urban poverty on children malnutrition. This is often compounded by poor awareness of the nutritional composition of easily accessible local nutritious foods.

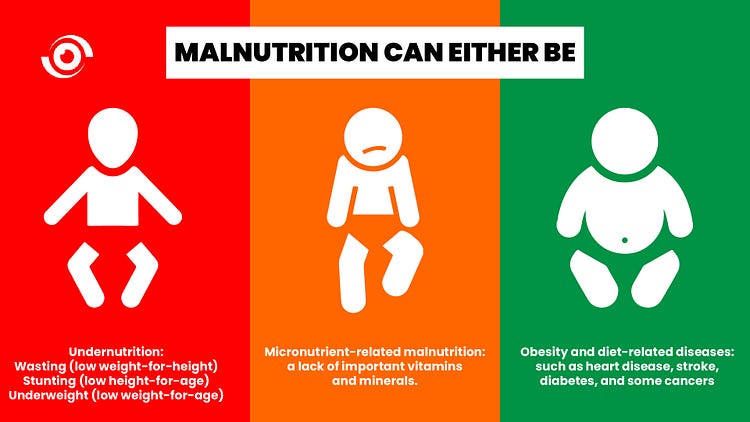

Malnutrition refers to deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients. Malnutrition broadly describes three groups of conditions:

- Undernutrition, which includes wasting (low weight-for-height), stunting (low height-for-age) and underweight (low weight-for-age)

- Micronutrient-related malnutrition, which includes micronutrient deficiencies (a lack of important vitamins and minerals) or micronutrient excess

- Overweight, obesity and diet-related noncommunicable diseases (such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and some cancers)

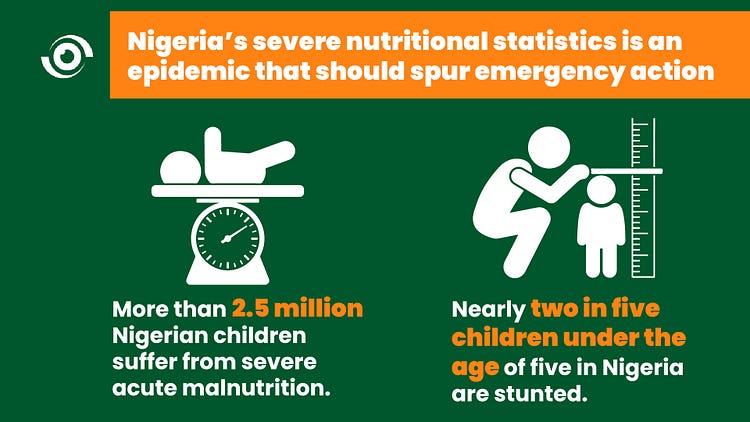

Nigeria’s poor nutritional statistics are an epidemic that should spur emergency multistakeholder action to mitigate its effects.

Nigeria’s nutrition landscape

In 2018, Nigeria Health Watch convened a health policy dialogue on nutrition with the title, “Our Nutrition Crisis: Considering Local Alternatives.” The aim of the policy dialogue was to explore new models and other high impact interventions and solutions to malnutrition, with a focus on local alternatives for preventing the onset of malnutrition. Behavioural change communications for nutrition issues, continuing nutrition education, as well as the role of the mass media were some of the recommendations proffered at the policy dialogue. Improving consumption of locally available nutritious foods still remains a viable recommendation. This could be made easier if the Ministry of Health provided an update on the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) guidelines for food items that different population groups, such as children should be consuming.

In Nigeria, the most prominent malnutrition condition is undernutrition. Undernutrition in the form of wasting, stunting, underweight, and deficiencies in vitamins and minerals makes children more vulnerable to infectious diseases due to the accompanying weak immunity, and could possibly lead to death if left untreated. Acute malnutrition, also known as wasting, develops as a result of recent rapid weight loss or a failure to gain weight. The degree of acute malnutrition is classified as either moderate or severe.

Globally, Nigeria has the second-highest number of children affected by malnutrition, with more than 2.5 million suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM), and only two out of every 10 affected child able to access treatment. Nigeria also has the second-highest burden of stunted children in the world, with a national prevalence rate of 37 percent of children under five. This means that nearly two in five children under the age of five in the county are stunted, or too short for their age. Seven percent of children under five are wasted (too thin for their height). In addition, 22% of children under five are underweight, or too thin for their age.

Nigeria’s nutrition landscape is as complex as many other low and middle-income countries. Rapid development, high population growth, and increasing rural-urban migration are leading to swelling cities and a new set of issues. While overprocessed, junk or fast food were considered contributors to overnutrition in urban areas, rural-urban migration and increasing media interconnectivity has seen both rural and urban consumers suffer the impact of a regular consumption of overprocessed foods, albeit on opposing sides of the malnutrition spectrum.

This is compounded by the rising levels of urban poverty, as many undernourished families do not have access to the few nutritional benefits of rural life, such as easier access to fruits, vegetables, and other home-grown foods, due to reduced distance between where food is grown and where it is eaten, also known as food miles. In addition, Nigeria’s urban population has grown rapidly with an average annual increase of 4.5 percent. Urban food demand is different from that in rural areas, as consumers seek more convenience foods that require minimal preparation, many of which are processed and enable ease of feeding compared to healthy food items that require preparation from scratch, resulting in a quickly evolving diet. Thus, for many, food consumption both in quality and quantity has decreased considerably, and the poorest who face disproportionate barriers to accessing healthy food, have an increased risk of malnutrition and undernutrition.

Contributors to the perception problem — ‘I’d rather be seen eating a pizza slice than a pawpaw slice’.

Poverty in the developing world is becoming increasingly urbanised. Relative and multidimensional poverty in particular will become more concentrated in urban areas, and the drivers and characteristics of poverty will be influenced by urban conditions. For the problem of malnutrition in Nigeria, this means that through excessively profit-oriented and manipulative marketing campaigns, healthy and easily accessible food options may have slowly come to be perceived as ‘low-status living’. As a result, Nigerians, like other global citizens who see fast foods as aspirational as they want to climb up the social ladder, may often opt for food and lifestyle choices which make them seem more successful and accomplished. This may seem like a middle to upper class problem alone, but data suggests that consumption of overprocessed or ‘junk’ food is contributing to the problem of undernutrition among the poorest.

This is an important concept when considering determinants of malnutrition because some studies show that eating behaviour was strongly influenced by social factors such as cultural food habits and physical environmental factors which present as temptations in the local food environment. This could mean that what people eat is determined by what they see eaten by people they aspire to become like, projected by the media, or their immediate environment.

What needs to be done ?

The National Council on Nutrition recently approved a five-year nutrition action plan to guide the implementation of interventions and programmes against hunger and malnutrition across all sectors in Nigeria. The National Multi-Sectoral Plan of Action for Food and Nutrition (NMPFAN) will run from 2021–2025. It hopes to reduce the proportion of people who suffer malnutrition by 50% and increase the exclusive breastfeeding rate to 65%. It also aims to reduce the stunting rate among under-five-year-olds to 18% by 2025 through the scaling up of priority high impact nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions. A multistakeholder approach is required to successfully implement this plan. Collaborative action across Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs), federal, state, local government and communities will help to reduce malnutrition in Nigeria.

Monitoring and implementation of key components of this plan of action, such as maternal health education for improved nutrition is key to achieving progress. Policies harnessing urban agriculture as a tool for improving food security and nutrition could also increase popularity and thus positive perceptions of local nutritious foods. This could help to ensure that the foods low-income earners eat are as nutrient-packed as possible.

‘If they need it, you need to make them want it’.

Private, for-profit sector marketing research suggests that it is easier to change people’s behaviour when the change in question is perceived to be part of their aspirations, goals, and desires. Marketing campaigns for locally available, highly nutritional foods need to be aspirational, associating these foods with the kind of lifestyle people would want to live and making them more appealing to children.

Targeted media strategies and nutrition campaigns can help improve nutrition in Nigeria. National nutrition strategies should include plans and policies that make the production of home-grown foods affordable and desirable. In addition, there needs to be a greater focus on nutrition education. Clear communications on what constitutes a nutritious balanced diet would enable increased uptake of home-grown foods. The absence of well-defined recommended dietary allowances of different food groups, also hinders the promotion of local nutritious foods.

Strategic education about nutritious locally-grown foods would go some way towards improving the public perception of local foods such that children like little Terwase grow up seeing nutritious foods as aspirational, by associating them with the kind of lifestyle that they would want to live. TV commercials also target children providing them with a misconception that many of the processed food items shown are healthy and nutritious.

Finally, it is useful to shift our thinking from the concept of just food security to the concept of nutrition security. To combat the effect of urban poverty on undernutrition, it is important to think not just about the quantity of food we are providing, but also the nutritional quality as well.

This article has really analyse the nutritional security of Nigeria. It’s a good resource for enlightenment at any gathering.

It’s apt for my seminar topic on healthy diet and lifestyle.