The joy of welcoming their new-born son was dampened when Delight Sunday’s parents saw that the infant had a large tear on both sides of his mouth. According to Mr Sunday, after visiting numerous medical facilities, unable to afford the cost of treatment, they “decided to accept their fate”. Delight faced a lot of rejection in school and at home, children avoided him. “At age 2 going on to 3, he didn’t understand why people ‘shooed’ him away when he walked up to them in the community where we lived,” he added. It didn’t help that he also had trouble speaking.

When Delight turned three, his parents heard of a surgeon who performed free surgeries for individuals with cleft lip and palate. “We had the opportunity to meet the surgeon and saw quite a number of cases worse than ours. The surgery was successful, and we were not required to pay a dime. My 8-year-old boy is now in wonderful health and has good speech”.

Overcoming barriers to care

Globally, 1 out of every 700 babies is born with a cleft lip. The causes of congenital deformities like cleft lips and palate among most infants is unknown. However, in some cases they are thought to be caused by a combination of genes, environmental factors or a lack of essential vitamins.

According to Dr. Ngutor Ver-or , Executive Director, Oral Health Advocacy Initiative (OHAI) Sokoto, Zamfara, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, and Yobe States report the most cleft lip births in Nigeria. Due to factors like barriers to care and poverty, a significant number of these cases go untreated.

However, non-governmental organisations like Smile Train, the world’s largest cleft charity are working to overcome these barriers by providing information, assistance and free surgeries to children in 77 different countries, including Nigeria.

Conceptualising OHAI

The Oral Health Advocacy Initiative (OHAI) is another of such organisations. As a resident doctor in the Oral and Maxillofacial Department of the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital in Kano, Dr Ver-or discovered that most people who visited the hospital with complicated oral and maxillofacial conditions always presented too late for an effective intervention. He then decided to take advocacy and enlightenment campaigns to communities “so people will know to seek medical attention immediately they have an issue with their oral health, or face,” he said.

Over time, the vision evolved and since 2012 — when the organisation was legally registered — OHAI has worked in over 750 communities in Nigeria and Africa taking cleft lip, and palate surgeries and other medical services to underprivileged populations at no cost. In addition to cleft lip repair, OHAI also provides oral health care for women and children and an oral cancer programme, among other things.

They have worked in 34 states in the country, treated over 10,000 patients and have carried out over 7,000 cleft lip repairs. In each state, they partner with the state government who provides the hospitals and health centres in designated local government areas (LGAs) where the surgeries are carried out.

Reaching out to rural communities

Every community outreach has a two-step approach. First, an advance team is sent out to liaise with the community leaders and mobilise the community members ahead of the arrival of the surgical team. Upon arrival, the surgical team first carries out a general assessment on all identified cases to know “if a person is fit for surgery”. If they are, “we take them in and prepare them. If not, we counsel them or refer them to go and look for adequate medical attention so that they are qualified to come for the surgery,” said Dr Ver-or. They currently have eight surgical teams and sometimes have multiple teams working concurrently in different states. Jeremiah, an anaesthetist with OHAI, said that each team works in one LGA per day and operates on 18–20 patients each day.

OHAI adopted the strategy of taking the outreaches to rural communities because stigma associated with the condition often causes individuals with cleft lip to retreat from public activity. According to Dr Ver-or parents have been known to send children with cleft lip to the village, throw them away or even bury them alive. They therefore go out with the aim of not only repairing cleft lips, but of also educating community members that it is a medical condition that can be easily fixed. “It helps that we go to their villages. They have a sense of security in being close to home. It also helps that we show them before and after photos. These help them make up their minds to have the surgery done,” he added.

Besides the usual medical supplies, one item that is a constant on their list of essentials is Ankara fabric. They stock up on those “because when we go to treat patients in villages, women come with their children, and sometimes the clothes they come in are worn out and somehow you know that is the best they have. So, if you as a woman are going to have an operation, we give you a wrapper. If it is a man, we give him a wrapper for his wife or mother,” said Dr Ver-or.

Navigating obstacles

The security challenges in the country have made it harder for OHAI teams to travel as readily as they used to. But they have found a way to navigate this challenge by working with the locals in any community they work in. The community members themselves provide security cover as well as intelligence on where to go and where to avoid. In addition, when they arrive in a state, they officially notify state security officials of their presence. These also provide them with the necessary security support.

As much as they love the work they do, the teams also recognise that they can do little without proper funding. Currently, partners provide 60% of the funding; the residual 40% must be raised. Partnerships with state governments sometimes helps reduce the cost of an outreach as they provide the facilities. They also work with volunteers. However, this doesn’t completely solve the problem as not having a complete surgical team readily available makes planning difficult.

More than skin deep

Statistics show that with 1 cleft case in every 1,200 births, Africans have the lowest incidence of cleft births. However, it is still a concern as untreated cases result in stigma, discrimination and difficulty eating, breathing, hearing, and speaking. Therefore, while cleft lip and palate repair is important for cosmetic reasons, its benefits are more than skin deep. It is also a health and survival issue. Surgery and treatment help the child get the nutrition they need, improves speech development, alleviates issues with breathing and generally gives them a chance at living a stigma free life.

But beyond surgery, intense awareness campaigns should be carried out in states where the most cases of cleft lips are reported. Constant campaigns targeted at raising awareness and correcting misinformation and cultural beliefs around babies born with cleft lip might be the reason why a child gets the chance to thrive in life.

Addressing birth defects

At the Sixty-third World Health Assembly (2010), member states agreed to promote primary prevention and improve the health of children with congenital anomalies. They pledged to raise awareness on the importance of newborn screening programmes and their role in identifying infants born with congenital birth defects, and support families who have children with birth defects and associated disabilities, among other things.

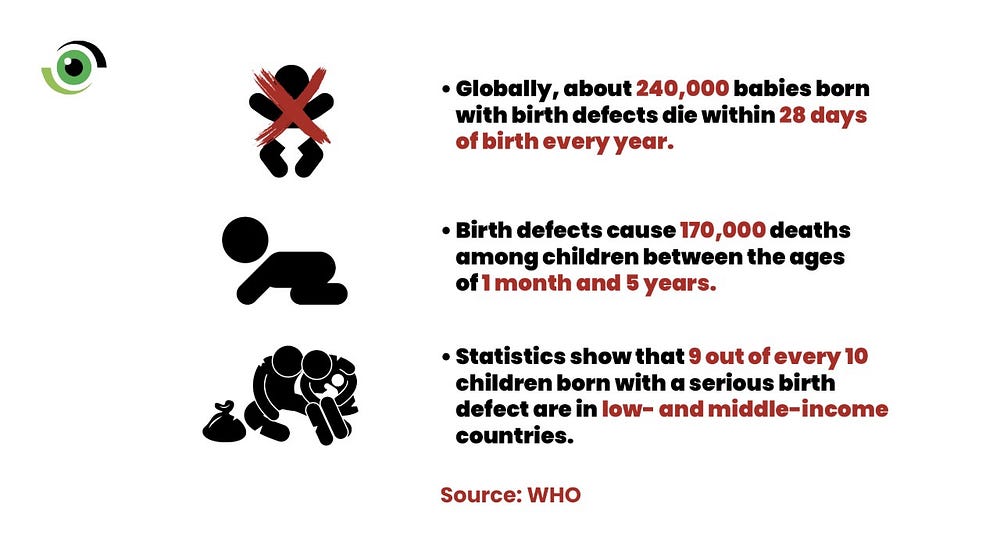

Globally, about 240,000 babies born with birth defects die within 28 days of birth every year. Birth defects also cause 170,000 deaths among children between the ages of 1 month and 5 years. Statistics show that 9 out of every ten children born with a serious birth defect are in low- and middle-income countries.

As government works to tackle neonatal and child health, it is vital that they take note of this resolution and work with private organisations like OHAI and Smile Train to combat the threat that birth defects pose and their contribution to neonatal and child mortality.