By Ohanu Dabri Olohije (Lead Writer)

In ensuring access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene for ALL, we cannot overlook the needs of remote and hard-to-reach communities.

Ubo community is nestled up a hill and down a valley in Rubochi Ward, Kuje Area Council. Ubo, also known as Simami is one of the remote villages in Rubochi Ward in the Federal Capital Territory. The population of barely more than a thousand is a mix of Gbagyi and Bassa tribes, and the majority of community residents are farmers, who grow guinea corn, maize, and yam.

Just like other surrounding villages in Rubochi, access to clean water is a major challenge and the residents rely on dug wells. According to His Royal Highness (HRH) Aliyu Kaura, the Aguma (Village Head) of Simami community, during the peak of the dry season, the wells dry up, leaving residents with only one alternative source of water- a stagnant shallow stream that serves all domestic purposes including drinking.

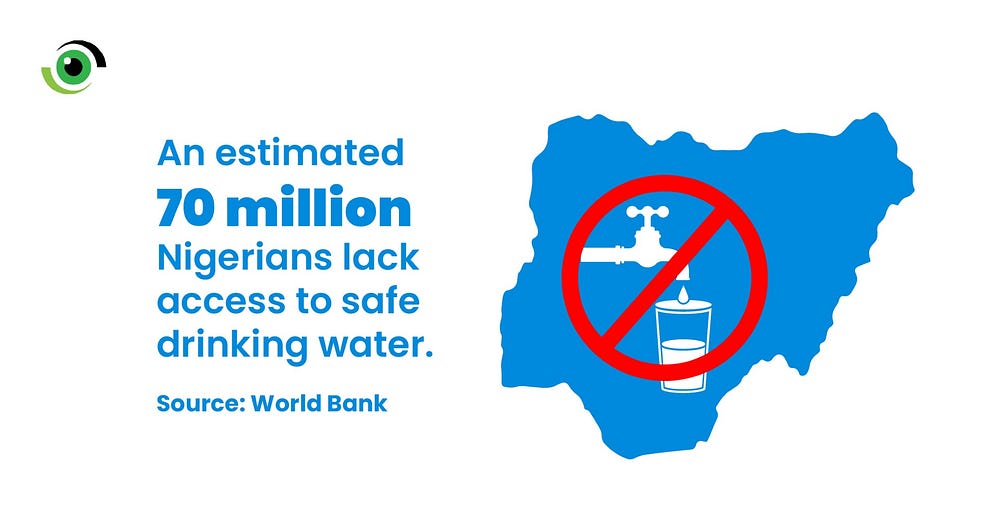

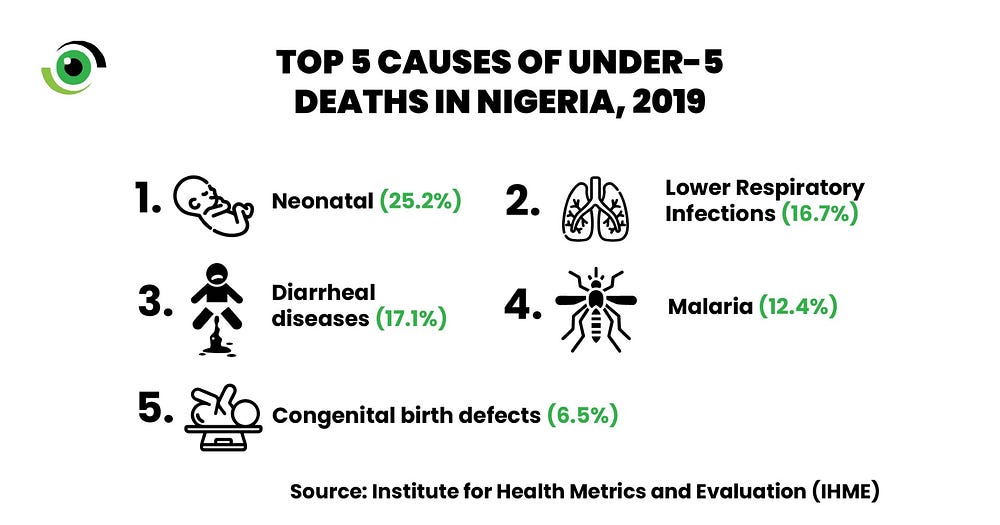

According to the World Bank, an estimated 70 million Nigerians do not have access to safe drinking water and at least 70,000 deaths occur in children under the age of five each year from diarrheal diseases. While the Simami community could not find a direct link between dirty water conditions and health issues, Cynthia Emmanuel, a 22-year-old mother of one shared how her son had experienced recurring vomiting, which she had treated at the Rubochi health centre. “He used to sick every time, he is vomiting for three days now until I take him to the hospital” Cynthia shared.

The only option

“We are used to it” HRH. Aliyu stated, adding that for several years, the community has struggled to access clean water, with women and children bearing the highest burden. During times of scarcity, it is not uncommon for women to wake up at 4:00 am to begin the 2.5-kilometer walk through a perilous route to the stream. This is a trip some of the women must make nearly five times a day to ensure that their families have access to water for their basic needs.

Halira Ishaka a mother of two sells moi-moi (steamed or boiled bean pudding) in the community. Every morning, she wakes up by 4:00 am to get water for her family. “During the dry season, water no dey we used to wake up 4:00 am before we get the water, only one time we go use am. Anything 10:00 am, we go again”. According to Halira, the water is used for drinking, washing plates and cooking with or without applying basic purification. “This is the water I use for the moi-moi. If I fetch, I wash beans, I fit boil am before I wash the beans then carry am go engine,” Halira said.

Access to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and clean water for personal and domestic use is a basic human right; yet basic sanitation and good hygiene remain a major challenge for a large proportion of the country’s population. Women and girls in Simami community must wake up very early every day to get water. Some mornings, the lack of water is a cause of disagreement among the women, who are desperate to get water before it becomes contaminated or runs out later in the day.

Physical inspection revealed that the water had an unusual colour and appeared to be used by animals, potentially leading to the spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera. “We dey drink am. We go let the water parboil, and then we cook. If na to drink, we go boil am first and add alum” 17-year-old Jamila Abdullahi explained.

Often forgotten

According to the Water, Sanitation, Hygiene National Outcome Routine Mapping 2021 (WASH NORM) report, only 10% of Nigeria’s population has access to all essential WASH services, and the situation is even worse in remote and hard-to-reach communities. Access to safe, clean drinking water is dependent on whether the community water system functions adequately. However, what happens when there are no water systems to begin with?

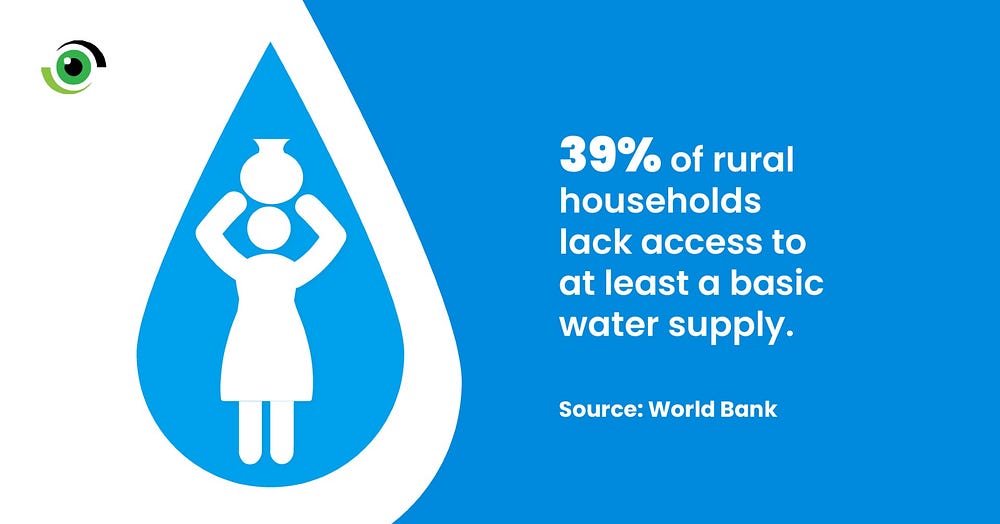

The water challenge in rural communities in Nigeria needs to be addressed urgently. Despite accounting for 46% of the nation’s population, 39% of rural households lack access to at least a basic water supply. These present a serious concern, particularly about the feasibility of achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6 by 2023.

Since the declaration of a state of emergency in the WASH sector in 2018, the government has implemented a number of initiatives to address the water challenges that rural communities face, including the National Action Plan for the Revitalisation of the WASH sector, which aims to improve citizens’ rights to access to clean water, sanitation.

However, some of these initiatives are not visible in remote communities like Simami, where residents believe they have been forgotten. Although the community has made numerous requests for a borehole or another reliable source of water, none has been provided by the Local Government Authority who is responsible for the establishment, operation, and maintenance of rural water supply schemes and sanitation facilities with support from Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Agencies and the Federal Government.

“Bamu da wani project a yanzu” –“There is no current project,” Usman Musa Takura a community resident said. “One chairman will come; another one will come. It’s the same thing they will do- after some time they will step down” Usman added.

Simami’s plea

“The solution is for the government to give a borehole” HRH. Aliyu appealed. Bridging the WASH infrastructure gap for rural communities is a matter of urgent concern. The challenge goes beyond basic hygiene to economic implications and gender inequalities. Women and girls in Simami disproportionately bear the burden of poor access to clean water. They are responsible for getting water for their families, which take a significant amount of time and effort. Their educational prospects are therefore limited, and they are exposed to a number of risks to their health and safety.

Halira shared that when there is a water shortage, she has to manage water for her moi-moi or not make any at all, preventing her from earning money to care for her family. Policymakers need to prioritise and commit enough sufficient resources to address the water and sanitation crisis in remote villages.

However, beyond providing water facilities, climate change poses a significant challenge as droughts cause rivers and streams to dry up. Many rural communities rely on naturally available water resources such as rivers and streams to survive, and their availability is determined by the amount of rainfall. Developing solutions to these WASH challenges should begin with a thorough examination of the impact of climate change in communities

The dry season is steadily approaching; for many, it is a welcome guest, however, in communities like Simami their concerns are heightened- how will we get water then?