In his shop in Relief Market in Owerri, Imo State, Sadisu Sani popularly called Zuma, is surrounded by vegetables of all shapes, sizes and colours. The middle-aged man has been in the business for over seven years and he understands how important it is to keep his wares fresh for as long as possible.

A social enterprise, Coldhubs is helping traders like Sani address this problem in Owerri and other parts of Nigeria. However, the impact of their work extends beyond the traders to the people who buy the vegetables and other food items.

An ‘expensive’ problem

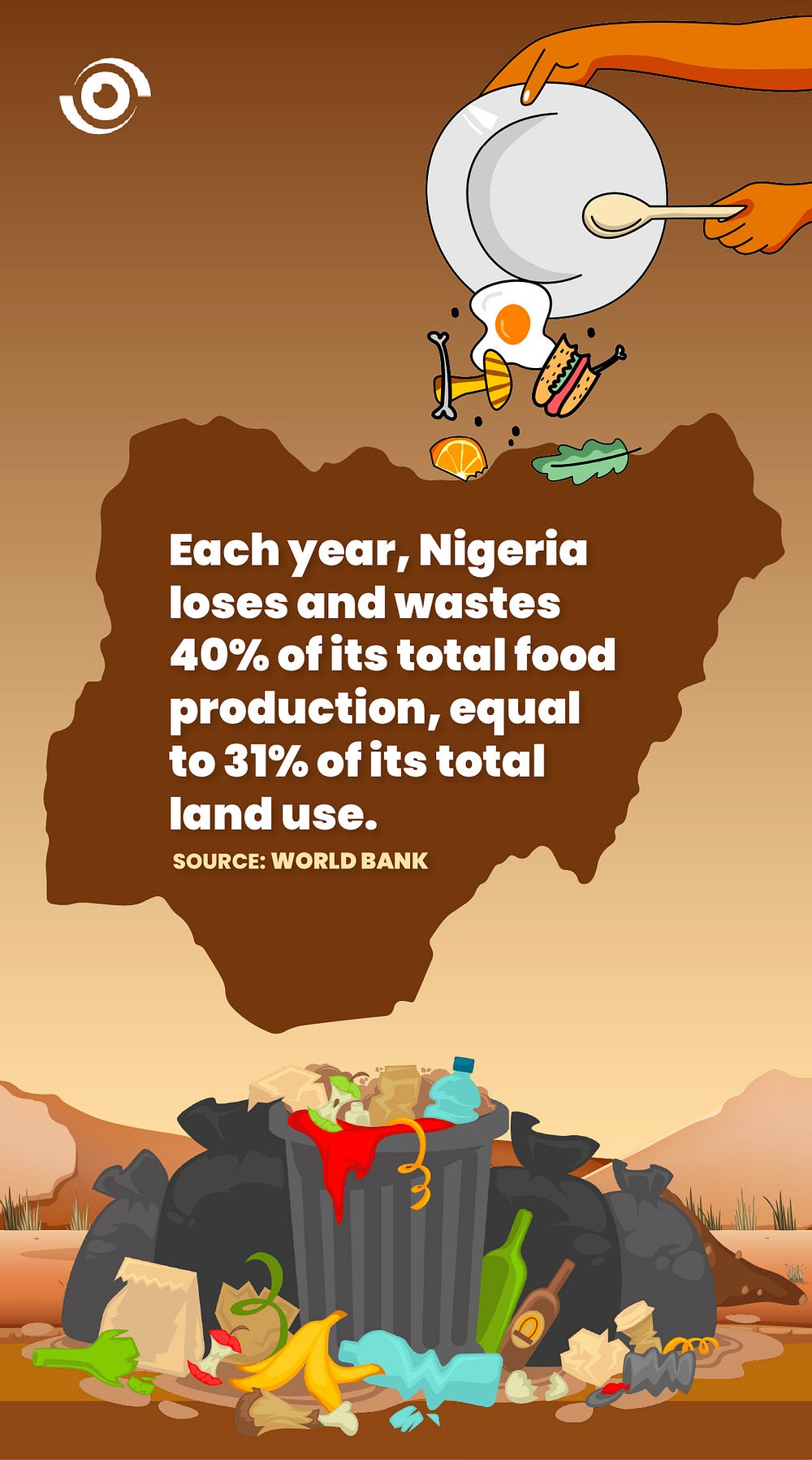

Globally, between harvest and retail, approximately 14 percent of the world’s food, valued at $400 billion is lost annually. At the same time, an estimated 17 percent of food is wasted at the retail and consumer levels. According to the World Bank Nigeria loses and wastes 40 percent of its total food production each year. This loss accounts for 31 percent of the country’s total land use and accounts for 5 percent of its greenhouse gas emissions.

Fresh farm produce starts losing its nutrient value almost immediately after harvest. Proper handling post-harvest and refrigeration helps slow down deterioration, ensuring that it is still fresh and nutritious when it reaches the consumer.

It is estimated that 37 percent of Nigerian agricultural production that requires refrigeration is lost due to inefficient or non-existent cold chains. Food spoilage due to a lack of cold storage costs 93 million small farmers in Nigeria 25 percent of their annual income. It is this aspect of the larger food security issue that the Coldhubs team is addressing.

A green solution

The hustle and bustle of a typical Saturday at the market isn’t loud enough to drown out the beeping sound from the giant refrigerator. The refrigerator, called the ‘hub’ is slightly smaller than a 40-foot shipping container and helps traders to keep their products, especially vegetables fresh until they are sold.

The hub is a walk-in, solar-powered cold station that offers 24/7 storage from two to about 21 days, to help increase the shelf life of perishable foods. It is installed in markets to enable traders’ easy access. “Using the sun to power the cold hubs means we are delivering the service using clean energy that keeps the environment safe,” says Chinedu Hardy Nwadike, Information Technology System Manager at Coldhubs. During the day, the hub is directly powered by the sun, while energy is saved in batteries. When the sun goes down, the batteries take over, Nwadike explains with delight.

However, they did not start out to address this problem. The founder, Nnaemeka Ikegwuonu has worked in agriculture for over 20 years. His organisation, The Small Holders Foundation, offers agricultural extension services to rural farmers, on farming best practices in order to help them get the most out of their investments. “He identified the problem of food waste when he engaged the rural farmers and Coldhubs was created to address that,” Nwadike reveals.

The first model, built in 2016 and based on the principle of air conditioning, was not successful. Lessons learned led to further improvements and the current version, according to Nwadike, costs approximately 15 million naira to produce one unit of the current Coldhubs model being used.

Before they set up operations in a particular location, the Coldhubs team engages with the market stakeholders and government agencies to find an appropriate space to lease for installing the solar-powered cold station. To ensure that the space in the cold station is properly utiilised, traders pack their goods in crates provided by the operators of the hub before they bring them to be stored.

Cooling as a service

“What is your name? Who sent you to bring their products? What is their name?” Esther Uwakwe asks a young boy who appeared not to have the details required to pick up goods stored in the hub. Uwakwe is the hub’s operator at the Relief Market and interacts with the traders who use the service. According to her boss, Amaka Anyasodo, Coldhub’s Regional Sales Representative for the southern region, “We have to be careful if not they can come and try to carry someone else’s goods,” referring to the young boy they were quizzing. They take proactive steps to prevent this by labeling the crates and keeping records of what each person brought for storage.

The hub operates a ‘cooling as a service’ model. “This means you pay as you store,” says Nwadike. A trader brings crates of their produce today and doesn’t pay anything until they are ready to pick them up. During check out, they pay a flat rate of N200 per crate depending on how long the crates have been in storage.

Jocelyne Agbo, who runs Farm on Wheels, an agriculture startup that empowers rural smallholder women farmers in northern Nigeria, says the hub is critical for reducing post-harvest losses. She works in a different value chain that doesn’t deal with fresh farm produce, so may not have need for Coldhubs. “But we still experience post-harvest loss mostly caused by reduced access to storage facilities and to the market” she says.

As of 2021, Coldhubs will have served over 5000 smallholder farmers and traders, provided employment to about 60 women and prevented approximately 30,000 tonnes of food from going to waste, says Nwadike. He adds that while this may seem like a drop in the ocean, compared to the amount of food wasted in Nigeria, the team is pushing to expand, despite any challenges. Coldhubs is currently present in more than 15 Nigerian states.

“We are not magicians”

The attitude of the hub operators is critical to keeping the traders coming back, Anyasodo says, as their ability to develop good relationships with the traders sustains the business. “You can see how she is engaging with them. We had a hub operator that didn’t relate well with the traders, and this affected utlisation,” she continues. Sustaining this relationship is critical because, while Coldhubs provides a critical service to the traders, it is the customer service that will keep them coming back, Nwadike notes.

The team is constantly organising demonstrations to show the impact of Coldhubs, as well as post-harvest sessions to teach traders how to properly handle their produce. The training is important because “we are not magicians,” says Nwadike. While Coldhubs can help preserve their perishable goods, they cannot do much if the produce are already in bad shape due to poor handling. So, preventing food waste and loss begins at the farm and other food aggregation points.

While initiatives such as Coldhubs is helping small holder farmers and traders store and deliver still-fresh farm produce to consumers, the government must supplement their efforts by playing a role. Good road networks will ensure that farm produce does not spend more time than necessary in transit. Stable power supply will lower the cost of operating cold stations for traders to store their goods, as well as enabling consumers to properly store their fruits and vegetables after purchase.

For Sani, his primary concern is to always keep his vegetables and other goods, fresh at all times, and he wants Coldhubs to assist him achieve this effort by any means necessary