Editor’s Note: In the wake of the #EndSARS protests that have rocked several Nigerian cities, we at Nigeria Health Watch take a look at some of the ways in which police brutality affects the mental, physical and emotional health of young people, and reflect on the conversations we must begin to have as a nation, if we are to grow a healthy, productive citizenry for the future.

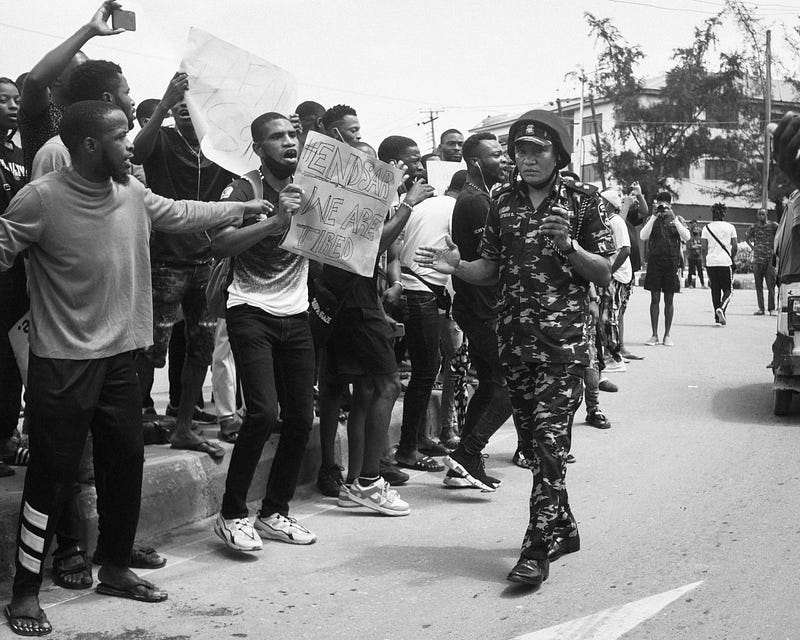

Young Nigerians have taken to the streets of major cities in Nigeria to demand for the disbandment of the country’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad, popularly known as SARS. The squad is a unit of the Nigerian Police Force (NPF) tasked with protecting citizens against violent crimes, such as armed robbery and kidnapping. Protesters are calling for the unit to be disbanded because of reports that SARS officers indiscriminately target and profile young Nigerians.

In June 2020, Amnesty International published a report on SARS, asserting that the unit continues to commit torture and other human rights violations while discharging their law enforcement duties. The report documents cases of extortion, torture and ill treatment by SARS between January 2017 and May 2020. It reveals a pattern of abuse of power by SARS officers and the consistent failure by the Nigerian authorities to bring perpetrators to justice. It highlights the deficiencies in Nigerian police accountability that contributes to, and exacerbates, these violations.

Protests which began on Wednesday, October 7, barely a week after Nigeria celebrated her 60th year as an independent nation, gathered momentum daily, mostly organised via social media platforms.

The response from various police and SARS teams throughout the country, some caught on camera and uploaded on social media, has further fueled the protests as people have lamented the violent nature adopted by law enforcement in responding. Protesters have repeatedly noted that as citizens, they have a constitutional right to peaceful protests without fear of retaliation, and have emphasised that the protests are peaceful. Videos shared have included shots of police spraying protesters with water cannons, with tear gas, beating protesters, and in some videos the sounds of gunshots can be heard as protesters run away.

On Monday, October 12, 2020, Nigeria’s President, Muhammadu Buhari announced the disbandment of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad and promised that this would be the first step in reforming the police force, calling those who have perpetrated acts of violence within the unit “a few bad eggs”.

His announcement did little to quell the fervour of the protests, as social media continued to be inundated with videos and photos of violent responses from police against protesters across the country. Many have also taken the opportunity to share their own stories of falling into the hands of SARS officials.

The hashtags #EndSARS #EndSarsNow and #ReformTheNigerianPolice have been trending, and public figures and social media influencers have joined their voices to the movement, with several organisations offering funds, supplies and legal support to protesters.

Joining the #EndSARS protest: Health advocacy or activism?

Young people from all parts of Nigeria and from various backgrounds joined the protests. For many, this is an opportunity for them to lend their voices to a cause that touches them deeply. Two health advocates shared their thoughts about joining the protest with Nigeria Health Watch.

Atinuke Akande-Alegbe works as a health communications officer. She joined the protest in Abuja over the weekend. “I was initially scared to join physically. But you can’t say you advocate for health and not be bothered about police brutality and injustice. It is a public health crisis too,” she said, adding, “Na who get life dey advocate for health! Can you advocate for the dead?”

She noted that young people are a huge target population for the work she does in health development, and the protests are not anti-police. “Can we fight for sexual and reproductive health and rights for dead youths? What is EpiAFRIC’s Health and Tech community without the youths? They say SARS officers are underpaid and that is why they extort and harass youths. Nigerian health workers are underpaid and they don’t steal from or kill their patients. They go months of selfless service without salaries. In fact, one of our demands includes an increase in police officer salaries. So we don’t hate. We are fighting for them too,” she said.

She said not knowing what will happen when you encounter a police officer has resulted in many young people living in fear. “We have so many stories to tell. Nigerian youths continually live in fear of those who are supposed to protect us. Some of us have PTSD when we see police officers, because you don’t even need to do anything wrong before they ‘waste’ you,” she said, adding that the protests are not meant to cause trouble, but to highlight the fact that police brutality has become out of hand.

“We are protesting online and offline. We are not causing trouble. We have just one ask — stop killing us. Is it too much to ask? Tomorrow, we will call out our leaders for the bad healthcare system, but today, we just want to live!” she said.

Dr Jacqueline Lambert is an Aesthetic Physician. She joined the protest in Abuja on Sunday, October 11, 2020. She said she anticipated that young people would one day demand good governance at all levels. “So when I decided to join the protest on Sunday, I was mentally and physically prepared,” she said. “However I prayed and hoped for a peaceful and calm protest without any violence. Did I see myself becoming a victim? NO. But these things happen.”

Lambert said she and another person were assaulted by police officers in the course of the protest, despite the fact that the young man with her introduced himself to the officers. “This didn’t deter them. All seven of them took turns in hitting us with wooden and iron batons. I had to play dead for the beatings to stop,” she said.

She shared photos of her bruised head, arms and legs on her personal Instagram handle, and told Nigeria Health Watch that the harrowing experience left her with some profound realisations. “The realisation that anyone can be attacked, regardless of your status quo in this country. So long as you are without a police escort, you could be the next victim of a trigger-happy or angry officer of the law,” she said.

Many other young health sector practitioners and advocates joined in the protests or supported the health and well being of protesters. Dr. Ikpeme Neto of Wella Health explained his support in a tweet, “I’m supporting healthy protests for all. I urge all health professionals to do the same. Police brutality is a public health emergency and we must provide care to all affected.”

Dr. Lambert agrees. “Police brutality is a public health issue and should be treated as such. As a medical practitioner, we not only lose young people to illnesses and diseases anymore, we lose them to police brutality. Use of excessive force and communal violence by the police leads to premature morbidities and death,” she said.

The public health challenge that police violence poses

The biological effects of violence have become increasingly better understood. They include effects on the brain, the neuroendocrine system, and the body’s immune response. Consequences include increased incidences of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and premature death. The health consequences of violence vary with the age and sex of the victim as well as the form of violence. From child abuse, sexual violence, intimate partner violence, bullying, and physical abuse. Violence over the past three decades has become not only a criminal justice issue, but also a public health concern.

Living in conditions of excessive police violence adversely affects health. Law enforcement is meant to protect citizens from harmful elements of society and citizens are meant to trust law enforcement in an ideal society. It is this trust that should ensure that citizens do not take the law into their own hands, but rather allow law enforcement officers to provide and pursue justice. When this trust breaks down or is breached, public life descends into chaos. Excessive police violence results in several public health problems.

Increased disease burdens and loss of years of life

Earlier this year, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the killing of George Floyd and the ensuing Black Lives Matter protests in the United States brought police use of force into focus again, with some people making the point that officials should regard police violence as a threat to public health.

Researchers linked police violence to poorer overall health of black communities, and to an increase in diabetes, obesity and hypertension. In addition to poorer health, some researchers also examined the years of life lost (YLLs) as a result of police violence. YLLs estimate the number of years a person might have lived if they did not die prematurely. This 2018 report on YLLs in the USA due to police violence explains that YLLs is a key metric for evaluating public health, and is used to compare the burdens of diseases and injuries across different populations and health conditions. Police violence and brutality is contributing to poorer health, increased disease burdens for victims as well as shorter lifespans.

Negative effects on mental health

World Mental Health Day was celebrated on October 10, 2020. The World Health Organisation (WHO) noted that the past months have brought many challenges: for health-care workers, providing care in difficult circumstances, going to work fearful of bringing COVID-19 home with them; for students, adapting to taking classes from home, with little contact with teachers and friends, and anxious about their futures; for workers whose livelihoods are threatened; for the vast number of people caught in poverty or in fragile humanitarian settings with extremely limited protection from COVID-19; and for people with mental health conditions, many experiencing even greater social isolation than before. The goal of this year’s World Mental Health Day was increased investment in mental health.

The fear of facing a potentially violent encounter with the police can lead to negative effects on the mental health of young Nigerians. Many people may experience increased stress whenever their interactions involve police officers because of past experiences or stories of the experiences of others. Anxiety, trauma, hopelessness and fear of future police encounters are all stressors that can negatively impact the mental health of people who have faced police violence.

Scholars have noted health equity issues that manifest in certain communities where police violence is a public health issue, for instance, that young urban men who have faced police brutality are especially prone to mental health challenges that include emotional trauma and anxiety.

Dr Lambert points out that victims of police brutality are impacted negatively in all areas. “Survivors of police brutality suffer physically, psychologically, emotionally and financially. Government and private organisations should set up funds in tackling this,” she said.

A complex road ahead with no quick fixes

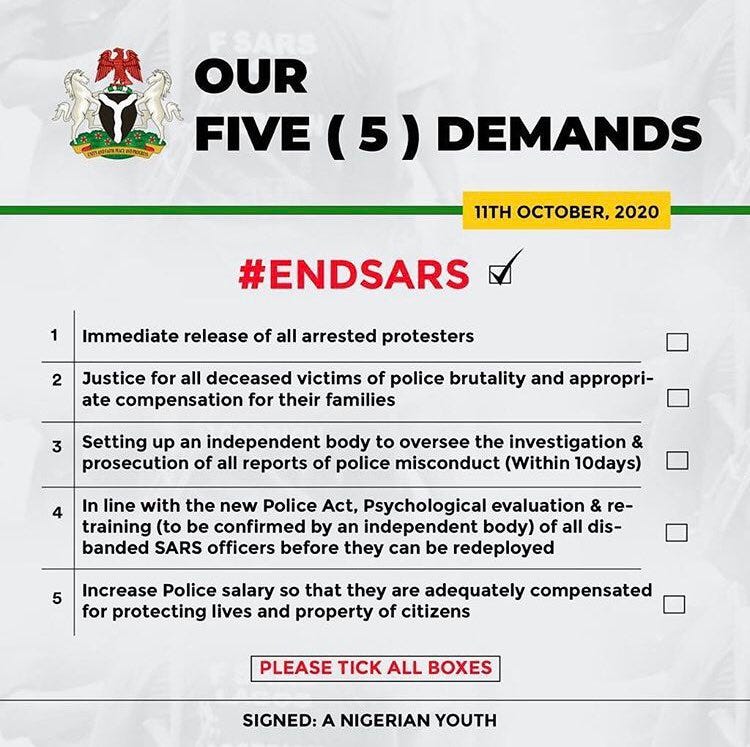

On Tuesday October 13, the announcement came that the Federal Government had conceded to the five demands of the #EndSARS protesters, which included providing psychological evaluations for SARS officers before they are redeployed into any other unit and increasing the salaries of police officers. Shortly after the announcement, the Inspector General of Police announced the formation of the Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) Unit to replace the recently dismantled SARS.

The question remains as to whether this new unit can effectively avoid the allegations made by young people against SARS. Countries like Georgia and Ukraine began to tackle police reform on the crest of mass popular movements seeking radical change, and ended up dismantling their entire police forces and starting over, with some success. Is this an option open to the Nigerian Police Force? We may also need to take a look at the nation’s use of force policies. Nigeria has several policing laws that guide when and how police officers are to use force, but it is not clear how implementation of these laws has fared or what the consequences are for going beyond the law.

Dr. Lambert says checks and balances must be put in place to ensure police officers are psychologically fit to handle their protector role and not abuse it. More attention also needs to be paid to the continuous on-the job training of police officers. “The police force must be reformed and its members should undergo a compulsory psychological evaluation annually,” she said, adding that “Officers accused of misconduct and abuse of power should be investigated and punished appropriately. If there are severe consequences for misconduct, cases of brutality wouldn’t thrive and only then would we feel safe and trust the system.”

And rebuilding the trust that has been breached is central to ensuring that as a society we can work to stop police brutality from happening and institutionalise effective public health support systems for those who have been victims of police violence, in order to protect their physical, social and mental health and well-being. In doing this, we will be protecting the future of our country, our young people, and preparing them to be responsive, confident and healthy leaders, both in mind and body.