Editor’s Note: This week’s Thought Leadership piece comes from Women in Global Health (WGH) Nigeria, an organisation that was established to bring visibility and recognition of Nigerian women, shape global health programming and advocacy, and reform policy and in communities in Nigeria and the diaspora. They analyse the reasons why more women are not seen in leadership positions in Nigeria’s health sector, and proffer solutions for what the country must do to change this narrative.

In many sectors in Nigeria, there is a considerable lack of female presence at the helm of affairs, and the health sector is no exception.

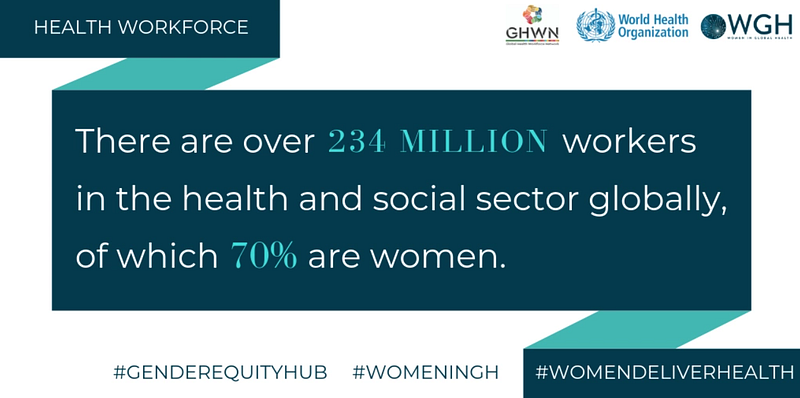

Even though women in the health workforce constitute over 60% of the health workforce, the majority of these women in the workforce are concentrated by weight in informal, low-status and low-paid “care” roles. Nigerian women have a less equitable representation in the sought-after and consequential professional and leadership positions.

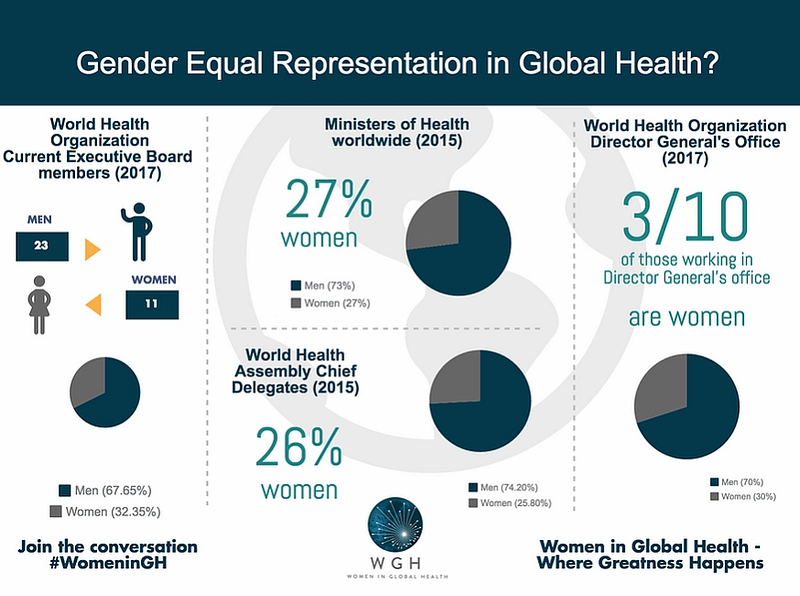

In the Nigerian academia sector, only a few medical institutions of training are female-led at the highest senate level. Similarly, of the members of the principal health-decision making body in Nigeria, The National Council on Health, only a mere 11% are women. It is not a surprise therefore, that in 60 years of the country’s independence and development of the health sector, there has only been one female health minister in the country.

Female leadership in the health sector is not only important to make a case for inclusiveness, gender equity and representation in global health leadership, but a lack of this representation can also be said to have implications for the health outcomes and indices in Nigeria.

All genders of the population in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) are affected by poor health indices, but gender minorities experience a disproportionate burden of disease and death. This is due to inequities of access to basic healthcare, nutrition, education, and a lack of financial inclusion and empowerment.

Rectifying this situation is critical to national and continent-wide development. A persuasive example is with maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa, to which Nigeria accounts for 20% of global maternal deaths, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Maternal mortality is devastating to families both in the short term and long term. Children in households where a maternal death has occurred are over four times more likely to die than other children. Maternal mortality influences an increase in child mortality and contributes heavily to poor health indices of children in Africa.

To underscore the effect of gender equity, studies have demonstrated that gender-focused policies improve when there is equitable representation of that gender in policy development and implementation. If we had more women in health leadership positions, we would demonstrably experience better policies that target women and children, ultimately influencing a generally more positive societal impact.

Extensive global research from McKinsey, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has demonstrated a positive correlation between increased female participation, representation and diversity in leadership with improved organisational outcomes and performance.

If gender equity and presentation in leadership improves health indices, is important in development, and builds better institutions, why does Nigeria, as a country that will benefit from all these above listed, have such a dearth of female leadership, and especially in health?

First, we must examine the matter of qualification, and question if women in the health workforce are less likely to be professionally qualified than their male counterparts, and thus are unable to assume these leadership positions.

After the question of qualification is suitably answered, we then must ask if the leadership gender gap is caused by a gender-specific lack of interest or desire for leadership? Is it possible that Nigerian women lack that desire?

We refer to anecdotal evidence here about female health care professionals in Nigeria, which proves otherwise.

Nigerian women in almost all sectors are strikingly ambitious and their role in the health sector is not an exception. Despite this, both anecdotal and a cursory data-scoping evidence show their male health professionals being better placed for more career opportunities and rising faster in the system. In contrast, Nigerian women often refer to systemic “barriers” that impede them from actualising their leadership aspirations.

The most pertinent of these barriers are the gender bias and discrimination at work faced by many women in the health care sector. Like many places globally, Nigerian women reportedly experience enduring sexual harassment from close colleagues, and often people in power. This led to the development of the global Me Too movement .

There are also cultural barriers that impede women from experiencing their best potential in the workplace, as they struggle to be accepted as equal to their male counterparts. This patriarchal hegemony is also necessary to the perception that the woman is weaker and cannot perform as well as her male colleagues, encountering difficulties in advancement if she is perceived as outspoken, while at the same time precluding her from opportunities, trainings and promotions when pregnant, if she is hired at all.

Paradoxically, the critical career-building years between receiving a graduate degree and obtaining a leadership role are also a woman’s reproductive years, when “the fast track and the reproductive track are on a collision course”. There is also the ever-present conflict between work and family life, for which because of the gendered role of home building, the woman is more affected than the man is. During this period, most women need to sacrifice their immediate career aspirations to focus on their families, while having to spend the rest of their career striving to catch up with their male counterparts. Often with the barriers afore mentioned in place, she would never catch up.

Of final but important note is a dearth of a promoted role models of women in leadership positions.

For the few women who have been able to beat the odds and arrive at leadership, there is a paucity of a sustained system effort and organisation to reach and guide younger career women through this path to leadership. Mentorship and networks are important in a way that is essential to today’s workplace. For men for instance, it is well proven that “mentor-mentee” “old boys clubs” are as essential to getting ahead to any other factor.

Solutions to leapfrog women into leadership

Despite the barriers, there are solutions that can address or in other cases leapfrog these barriers and ensure the equity in leadership in the Nigerian health sector. These critical steps will form the base of a sustained systemic re-design for gender, especially towards women, and especially in the health sector.

First, in the academic sector, institutional changes and the implementation of effective policies to address gender-related issues such as discrimination, sexual harassment and maternity leave will level the playing field for women aspiring to leadership positions.

Second, an increase in the number of scholarships and fellowships targeted towards young girls interested in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) is needed to encourage and sustain interest from an early age. This should be fostered by partnerships from the private and public sector to come together deliberately, to achieve this. These partnerships should also make strategic investments towards providing leadership training grants and scholarships to enable women attain vital leadership skills early on in their careers.

Third, it is important that the few women currently in positions of leadership consciously and intentionally open “merit-based” doors for other women. This could be through formal mentorship or the creation of networking opportunities via collaborative platforms such as Women in Global Health.

Strategically investing in raising and nurturing a crop of skilled and motivated women in global health has the potential of growing huge returns in a new generation of female leaders who are not only poised to lead, but are equipped to lead effectively and impact positive change in global health.

After tackling the barriers that impede the female gender, the system must then look at the male gender.

We need to engage men, both as people who uphold the gender hegemony, and also as people who are gender-allies of women. Applying the above systemic recommendations would need involvement of men for successful implementation. For this to happen effectively, both women and men need to first perceive women as intellectually equal. Male leaders should then set the tone for inclusive leadership; speak out on issues such as sexual harassment; and ensure that non-discriminatory policies are instituted and implemented.

It is time to use that same patriarchal system that has hindered women for decades by working with influential male leaders who understand the enormous benefits of having women in healthcare leadership and are committed to using their power and influence to enable the rise of women.

Women in Global Health (WGH) Nigeria is a chapter of Women in Global Health. The chapter’s main goal is to be inclusive by incorporating all genders from all career stages and levels within the healthcare space regardless of tribe, religion, age, and socioeconomic status, to achieve gender transformative leadership. The Nigeria Chapter of Women in Global Health is deeply committed to advocating strongly and supporting this long overdue tilt in the power balance towards a more equitable, impactful, and sustainable future for global health leadership.