I struggled with feelings of anxiety and depression for nine months during my first pregnancy in 2016. I spoke with my gynaecologist several times about my different mood swings, but he felt I should be excited because I was having a baby. Sometimes I felt happy about having a baby, but most times I felt sad. I was so forgetful, I cried a lot and was unable to concentrate at work. The mood swings continued after I had my baby. I often felt unhappy and was easily angered. My mother in-law visited me at the hospital and noticed that I was not happy. It was clear that she did not understand why I might have felt unhappy, as she felt I should be happy. By the time the naming ceremony came seven days after, I wished I could go somewhere to be by myself but could not. Added to this, at that same time my younger brother died, and this made my feelings of depression worse.

Three months later, I was still having these same ‘‘mood swings’’. I knew something was wrong, but I had no idea what it was, until my husband’s friend who is a medical doctor visited us and told us about Postpartum Depression. This made me see that it was not a mysterious problem, but rather it was an issue that is hardly discussed. I went online to read about PPD and how women coped with it. Postpartum Depression was discussed in an article in Granta magazine by Dr. Ike Anya where he mentioned that medical practitioners ‘‘still look at depression as a largely Western illness and as such a lot of cases are missed”. I decided to fight the depression for the sake of my baby and mental health.

During my second pregnancy in 2019, I experienced perinatal depression. This I found out was depression before giving birth and this time I kept it to myself, because I saw the same gynaecologist at the same hospital as my first pregnancy. After I had my baby, I did not breastfeed her for 2 days, neither did I feel any sort of bond towards her until after her first birthday. Perinatal depression affected my relationship with my baby and I could not get the help I desperately needed from my doctor. I struggled with depression and anxiety for three years, determined to fight it. It made me realise that no matter our level of education, irrespective of our background, culture, and religion, perinatal depression is a reality for many women.

Why the focus on mental health support?

Mental health care has had many advocates, but funding and commitment for sustained implementation and scale-up of services has been limited. It has been flagged as a priority area for accelerated implementation by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to promote health and wellbeing.

Depression and anxiety disorders cost the global economy US$1 trillion per year. This article discusses perinatal depression and anxiety amongst pregnant women.

What is depression?

Depression is a mood disorder which is characterized by prolonged sadness and loss of interest in daily activities. Some of the symptoms include numbness, poor memory, thoughts of committing suicide and lack of concentration. Perinatal depression refers to depression while pregnant, while Postpartum Depression refers to depression that occurs after childbirth (minimum of six months).

Globally, about 10% of pregnant women and 13% of women who have just given birth experience a mental disorder, primarily depression. This percentage is higher in developing countries, with 15.6% of women during pregnancy and 19.8% after childbirth. Mild and severe cases of perinatal depression exist, and in severe cases some mothers’ might want to commit suicide.

In Nigeria, the reported rate of depression in pregnant women is 10–30%. It is 47% higher in pregnant adolescents compared to their adult counterparts, because of their low socio-economic status and fear of having poor parenting skills. A study was conducted in Abeokuta North in 2016 to assess perinatal prevalence in 276 women using Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS); an international tool used to assess depression. Findings showed that out of these women; 24.5% were diagnosed as depressed. Another study conducted in 2019 in the South East, with a sample size of 270 women using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to measure depression, and anxiety was measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A) for Postnatal depression. Ninety — two women were diagnosed as possibly depressed; the HADS-A identified 89 with anxiety symptoms, 69 had both depression and anxiety symptoms.

Studies showed that despite the numerous consultations pregnant women have with health workers, most of them do not disclose symptoms of anxiety or depression to them. Maternal mental disorders are treatable and there is evidence-based treatment for depression in mothers.

Where is Nigeria when it comes to providing mental health support?

At the National level, there are several issues facing mental health support for maternal health. These include low publicity of perinatal depression, low priority of perinatal depression as a mental health issue in clinical settings, and an inadequate number of psychologists and psychiatrists in the country.

Nigeria also has no national psycho-social support intervention. The 2018–2022 National Strategic Health Development Plan did not make provision to address perinatal depression in pregnant women. There is no available research and data that is specific to prenatal depression at national level in Nigeria, as well as no nationally approved websites from the Federal government, Psychology and Psychiatric Associations for the provision of online consultation for starting a therapy. There is also no information nor online link to provide information on psychiatrists for online therapy on the website of Association for Psychiatrists in Nigeria.

At the community level, there is a general perception that mental illness is supernatural and so cannot be treated medically, as seen in this mental health survey. While there are government mental health institutions, most of the mental health support and intervention is provided by private organisations. Treatment coverage for mental illness is still extremely low, and although effective evidence–based care is available, provision in health facilities is lacking.

When it comes to healthcare services provided in Nigeria, antenatal care is designed to focus more on the baby’s growth and development, with less focus on the mother’s mental health especially for women who have had a baby before. Also, Health Maintenance Organisations (HMOs) usually do not cover the cost of a therapist, either a psychologist or psychiatrist, and this may contribute to poor health seeking behaviour for mental health services because of affordability.

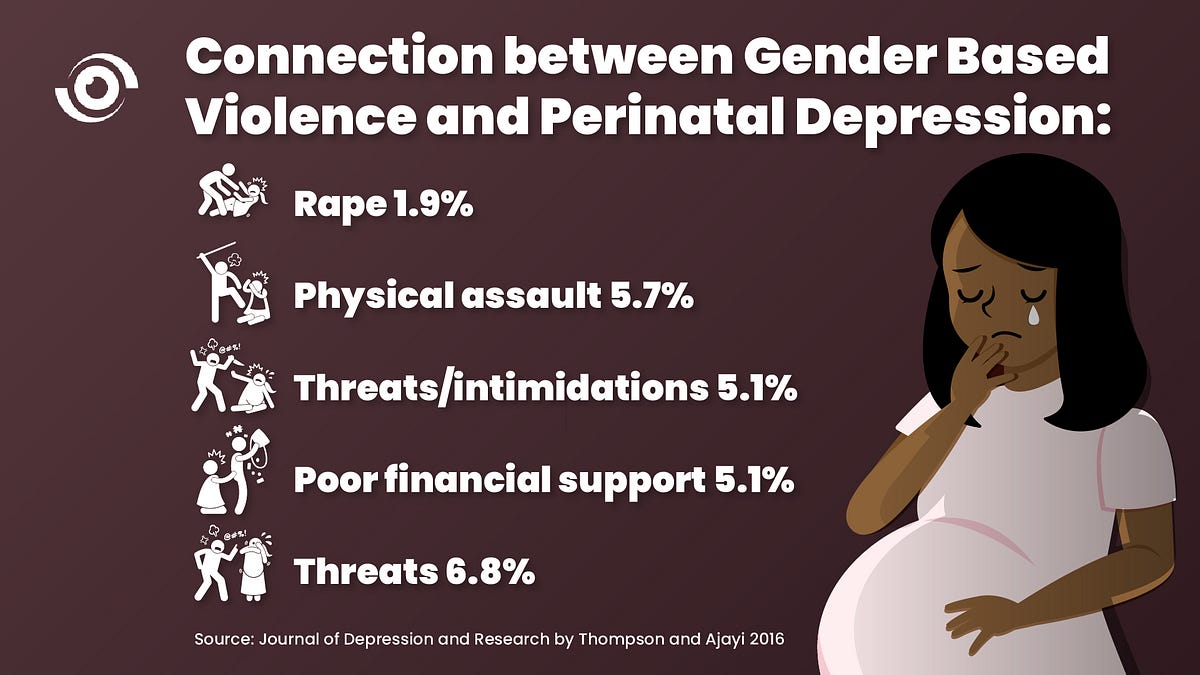

Nearly all women can develop a spectrum of mental disorder during pregnancy and within their first year after childbirth. Findings from a recent study done in Abeokuta, South-West, Nigeria, to ascertain the relationship between social inequities and prenatal depression found a strong connection between gender-based violence and prenatal depression.

Family history may also be a factor when it comes to mental illness, including a history of mood and anxiety disorders, a history of Postpartum Depression, a history of premenstrual dysphoric disorder, which is a severe condition that affects a woman’s emotions and behaviour, a family history of perinatal psychiatric illness, and a history of childhood abuse.

When it comes to perinatal depression, many pregnant women and their relatives fail to recognise its symptoms and underestimate its severity. This contributes to their reluctance to seek care. Perinatal depression is sometimes perceived as sorcery, witchcraft, a possession of evil spirits, divine punishment from God, a sign of maternal incompetence. A desire to be a super mother, or a phase that will go away after childbirth. Perinatal depression has both short- and long-term impacts on both mother and child. A study found that there is an association between perinatal depression and labour complications, such as prolonged labour, Postpartum Depression, non-vaginal delivery, pre-term labour, and delayed cognitive and linguistic development of the baby, to name a few.

What must Nigeria do to provide better mental health support services for mothers?

Building a robust service network for maternal mental health in Nigeria is a collaborative process that includes every sector, from academia to ministries, from policy makers to the community and health facilities.

Academic institutions should continue to do research to determine the gravity of perinatal depression at community level in Nigeria. They should also teach behaviour change communication on mental health to students in higher institutions and integrate mental health course as mandatory for all first year Students with the aim of increasing mental health awareness in youths.

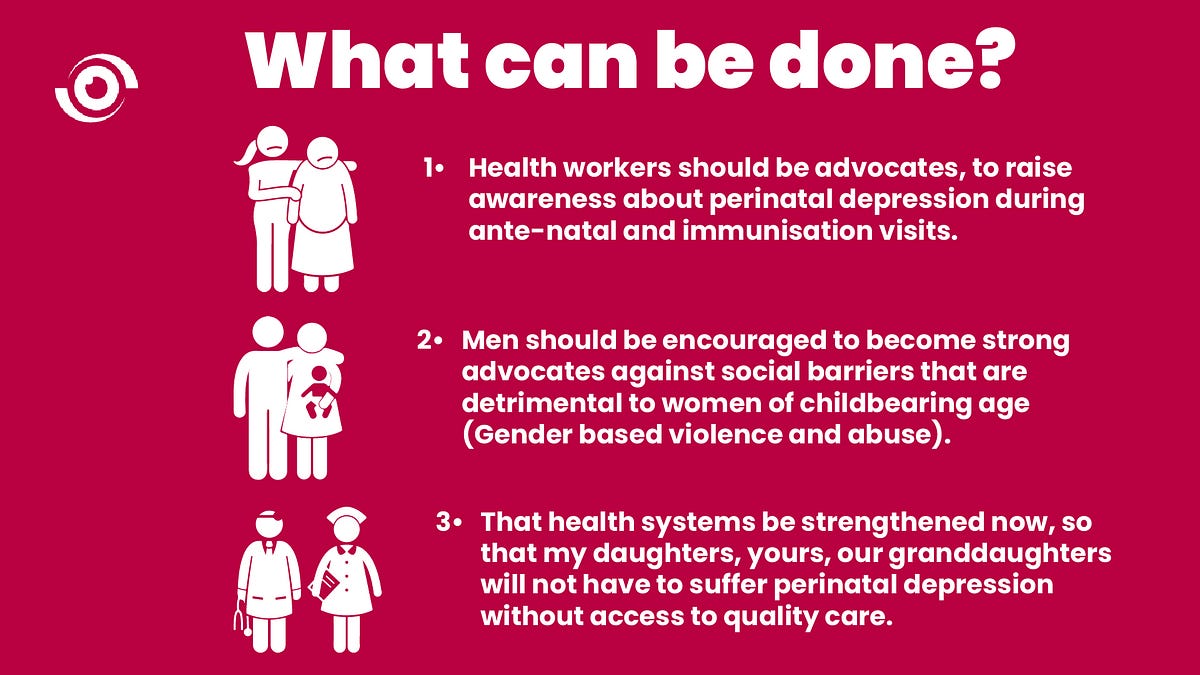

Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) should integrate a mandatory assessment of depression and anxiety in antenatal and immunisation services, at a minimum of 6 months after childbirth. They should also include indicators on perinatal depression and anxiety cases and support in the National Health Management Information System (NHMIS), and report perinatal cases as a maternal health indicator in subsequent demographic and health surveys.

Health Facilities should build the capacity of Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs) to enable them to identify pregnant women with symptoms of depression in communities. They should also incorporate an initial depression survey with a nondisclosure agreement for every first antenatal visit and follow up during routine immunisation visits for at least one year. They can also incorporate mental health courses into Continuous Professional Development and Continuous Medical Education for health workers and establish linkages in communities between key or dominant religious groups and Primary Health Centres. Finally, there should be Community Mental Health Facilities (CMHF) in rural areas focused on promoting, educating, and counselling women on their mental; this will in turn address shortage of psychiatrists and psychologists in Nigeria.

Religious leaders should take part in increasing awareness of the dangers of perinatal depression through their messages. Prayer houses should also be linked to nearby health facilities and relevant community-based organisations to whom they can refer members who come to them for help.

Foundations should increase advocacy on mental health support for pregnant women. They can advocate for the integration of a routine mental health assessment for pregnant women with referral to non-government organisations for psychosocial support. They can also provide technical support to ministries, departments, and agencies to conduct needs-based assessments. These can provide sufficient data at the national level to justify why management of perinatal depression should be a priority in Nigeria. Foundations can also support the responsible Ministries by using a sustainable inter-sectoral approach to develop a roadmap for implementation of mental health support services for pregnant women in all hospitals.

Finally, policy makers and the government must finalise and sign the National Mental Health Bill into law and commission a gender balanced mental health agency. They should map out all Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) providing services in this area across the 36 States in Nigeria and establish an association which people can easily be referred to, if they need help. Through this association they can promote state-wide research and health insurance services on perinatal depression and anxiety. Policy makers should also allocate clear cut budget lines for mental health interventions in Nigeria and strengthen the effective leadership and governance of the mental health agenda through the establishment of a national agency in Nigeria.

Today on Maternal Mental Health Day, it is important that we draw attention to the many women who have to cope in silence. Being silent means the issue of perinatal depression and Postpartum Depression will never be fully understood and will not be addressed or prioritised by doctors, health workers, policy makers or society at large.

Are you in need of psychological support?

You can reach out to:

- Shewriteswoman: a mental health support organisation based in Lagos. They have a strong online presence, consult online and offline and travel to the North East to provide safe spaces for people to provide mental health support.

- An online archive of therapists, where you can receive services online irrespective of your location in Nigeria.

- Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiative: Makes it possible for people to seek care for their mental health without fear of discrimination and provide more insight on various models of psychological interventions across the globe.

- PsychNg offer services to individuals, couples and conduct psychological assessments

- BTH Wellness and Therapy provide services both offline and online services on Depression.

These are not recommended therapists; make sure to verify their licensure.

This is quite educative and inspiring. Information is power indeed. I am delighted to read this article

Hello Edward,

I appreciate the time you took to read the article, and thanks for the feedback as well.

Kind regards

This piece is nothing short of educative and informative.I’m better informed.Thanks Ifeyinwa

Thank you for the feedback Edith

I’m elated to come by this article. It’s more than educative, informative, it also comes with solutions to postpartum depression and other mental health issues. Bravo Edward

Ifeyinwa, I meant to commend