The young mothers in the community fondly call her “Aunty Dada”

Her first attempt at helping a woman deliver a baby was in a forest while escaping from insurgents. She had already seen several pregnant women die in childbirth in the forest and so at that point, she felt she had only two options. She could either let this pregnant woman suffer and die like the others before her, or she could try and help even with her limited knowledge. She chose to help and continued in the practice and at some point, during their escape, she helped a woman whose baby was already dead in the womb to deliver her baby. She said she only trusted her instincts to be able to do it.

Today, her practice inside a two-room unpainted building is no longer just informed by intuition, but by the experience she gained subsequently and, more importantly, by the skills and capacity she has developed through training by the Kabash Love Foundation (KLF) which targeted Traditional Birth Attendants (TBA) practicing in Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps across Abuja.

Dada Nguru is regarded fondly in the Kabusa camp for IDPs off the Abuja Airport road for her work helping over five hundred pregnant women deliver their babies successfully, in the four years since she was forced to relocate from the northeastern town of Gwoza due to the Boko Haram insurgency.

Liyatu Ayuba, another TBA in the Gwoza and Bama IDP camp northeast of Abuja, relocated in 2012 after her policeman husband was killed by insurgents and her son was maimed by a bomb blast. Liyatu watched her grandmother practice as a TBA and picked up the skills from her.

At the camp, Liyatu tried repeatedly to get treatment for her son, without any luck. Surrounded by young women who were getting pregnant, without easy access to primary health care, Liyatu decided to help these young women to deliver, relying on the knowledge acquired from watching her grandmother. Like Dada, she trusted her instincts and prayed to God to help her take deliveries successfully. Like Aunty Dada as well, she later received training in helping pregnant women deliver successfully, boosting her confidence and expertise.

The efforts of these women and others like them, though largely unregulated and seen by some nurses and midwives as encroaching on their professional territory, helps women deliver safely in areas such as IDP camps where healthcare services are sparse, and women and children are often vulnerable to illness.

A dire situation complicated by insecurity

In many parts of Nigeria, access to health services is already poor during peace time. The outbreak of diseases and conflict brings an almost total disintegration of the health system. When camps are set up for people fleeing from conflict, health services are often not considered and many IDPs find themselves reliant on sporadic outreach medical missions from NGOs and other humanitarian organizations for any healthcare.

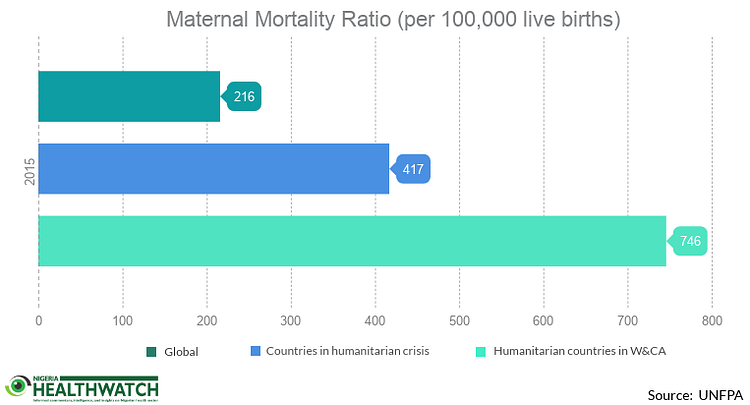

A 2015 statistics brief by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) shows that maternal mortality in humanitarian and fragile settings is 1.9 times higher than the world average. This means that if the global maternal mortality ratio is 216 for every 100,000 live births, countries with insecurity challenges have a ratio of 417 for every 100,000 live births. This is worse in West and Central African countries facing insurgencies or other humanitarian emergencies, where the maternal mortality rate is as high as 746 per 100,000 live births. Latest Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) 2013 data shows Nigeria’s maternal mortality rate is 576 per 100,000 live births. Even without the present insecurity challenges, there is much work to be done in Nigeria to reduce the maternal mortality rate. To reverse this trend, former UNFPA Executive Director, the late Professor. Babatunde Osotimehin, recommended an improvement in the number of midwives and other health workers with midwifery skills.

Adaptive solutions for safer deliveries

Keturah Adams, founder of Kabash Love Foundation and her team designed an intervention to reduce maternal mortality in IDP camps across Abuja. She said the original idea was “to get women to go to health facilities and have their babies, so they can have safe and infection free procedures with trained personnel.”

Their sensitization efforts targeted pregnant women in Bwari area council, about 20km off the Abuja — Kaduna expressway, focusing on educating them about the dangers of home deliveries. They used baby delivery kits as incentives to get women to visit health facilities for deliveries. However, they found that the women would take the delivery kits ahead of their delivery dates promising to return when they were ready to give birth, because they didn’t trust the primary healthcare facility staff to give them the kits when they were ready to deliver.

Adams and her team found out when they came back to evaluate their initial intervention that only one out of the 200 women they had worked with gave birth at the health facility. The majority had gone to traditional birth attendants like Aunty Dada and Liyatu. On probing further, they learned the women resisted going to the health facility to give birth for several reasons. These included the way they were treated by the health workers and the cost of care at the facility. The women also preferred the TBAs who understood their culture and way of life.

The KLF team then came up with a new solution- bringing all the TBAs practicing in 23 IDP camps around Abuja together, to build their capacity in performing safe deliveries. The training took place in the Gwoza and Bama IDP camp in Durumi, and the TBAs were taught modern delivery methods.

Adams said the training involved first unlearning some of the harmful practices by the TBAs like using toothpaste for the umbilical cords, tying umbilical cords with clothes and vigorously shaking the newborn after delivery.

They also provided basic delivery materials like hand gloves, chlorhexidine cream and cut clamps for the umbilical cord and taught the TBAs how to use them. The TBAs were trained by a nurse who volunteers for the organization.

Replacing guesswork with training & evidence

Fatima Mohammed, who resides in the Kabussa camp has successfully given birth to two children since relocating from Gwoza three years ago. Describing giving birth to five-week-old Aliyu and two-year-old Aisha as seamless, she said she was home in less than 20 minutes after both deliveries. Fatima said she prefers using Aunty Dada for her deliveries because she charges little to nothing and treats her with respect.

Rakia Adamu, another camp resident, is currently pregnant. She says Aunty Dada delivered her last two babies, and her satisfied smile makes it clear that she plans to come to her when she goes into labour.

Aunty Dada admits that in the past she would get scared if the pregnant woman had suspected postpartum haemorrhage, this is where women bleed profusely after giving birth. Now, thanks to the training by Adams and her team, she is more confident handling certain levels of post-partum haemorrhage with drugs contained in the delivery kit presented to her after training.

The training also provided her with skills on identifying the danger signs before delivery and referring these women to health facilities early. She has had over 100 successful deliveries since she started practicing in the camp.

A stop-gap measure, not the ideal

Even though her success handling deliveries has spread fast by word of mouth and many pregnant women from distant locations come to her for assistance, Liyatu Ayuba says she is honest with the women and advises them on the dangers of home delivery.

She said most home deliveries occur in unsanitary conditions, exposing the new babies, the mothers and even the TBAs to infections. She has taken deliveries without gloves in the past, before the training, and shared the story of delivering a baby inside a tent during a thunderstorm. On that occasion, just as the baby emerged, the storm blew the tent away and they all got drenched, — baby, mother and Liyatu.

On her own part, Aunty Dada confidently declares that she has never recorded any death since she started her practice, information which she shared with the KLF team when they carried out a needs assessment prior to the training.

While this is commendable but perhaps hard to believe, it is difficult to prove or refute due to poor record-keeping practices. Dada said the records she had kept were taken away by organizations who visited the camp, to make copies. The records, she says, were never returned and the organizations never came back with all the things they promised. Adams said many TBAs struggle to admit any deaths because they believe it spoils their reputation.

Dr. Godwin Ntadom, a Gynaecologist and Chief Consultant Epidemiologist of the Federation in the Ministry of Health, strongly believes TBAs have increased the maternal mortality rate in the country rather than reduce it. He says outcomes are better when pregnant women are assisted by skilled birth attendants and maintains that the Federal Ministry of Health has not adopted their practice as a line of action in maternal care.

“The TBAs have this fake confidence in themselves that they can always do it. By the time they are referring that baby or mother, it’s already too late,” He said, adding that most of the TBAs are old and untrainable.

A senior member of staff at the Head Office of the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria, who preferred not to be named, said the council is not concerned with regulation of TBA practice and that she personally knows nothing about it.

Important questions to ask are: What would the outcomes have been for the women and babies assisted by these traditional birth attendants if they had not been there? What is the evidence on the balance between the harms and benefits of using TBAs?

The Lagos State Government recently disclosed that TBAs accounted for 14,536 deliveries in 2015, lower than the previous year when there were 23,229 deliveries from 809 registered TBAs. The state government is now working to regulate and monitor their practice through the Traditional Medicine Board which issues practicing licenses to the TBAs.

The ideal situation would be for every pregnant woman to have access to a skilled birth attendant in a properly equipped health facility. Where this is not possible, and access to healthcare is unreliable, such as in the IDP camps, we must examine the best available options taking into account the evidence of effectiveness, the risk of harm and the importance of keeping the patient with their unique contexts and cultural peculiarities the focus.

Could training TBAs like Liyatu and Dada to help women deliver safely be one way of providing a stopgap measure until the health system is able to break down the barriers that prevent women from accessing care? Or should the resources and energy being put into these initiatives be focused on improving access to healthcare and the quality of healthcare provided in facilities? We at Nigeria Health Watch would love to hear your views.

I am embarrassed that my country Nigeria is proudly presenting to the world acceptance of illiterate TBAs in our DIP camps as the best we have to offer for birth attendance! The major reason why we continue to have the highest maternal.mortality ratio on the continent of because of failure to invest in skilled birth attendance but actual spend money trying to build capacity of illiterate and dangerous TBAs who have no skills whatsoever to manage any of the t commonest causes of maternal deaths I.e excessive bleeding after childbirth, eclampsia, obstructed labour, severe infections and abortion complications. We know 85% of deliveries will end normally even if doctors and nurses are not there. It’s the remaining 15% that we need to worry about and TBAs can’t do anything. Their best role is to refer!

TBA’s like native doctors are part of our heritage in Nigeria and they are not going anywhere. If you criminalise the practice or TBA’s they will go underground and more women will still die. The challenge we have as nation whether it is in a DIP camp or not is not just the lack of trained birth attendants/HCW’s but how to retain them in many rural areas and communities. Every trained HCW is looking for greener pastures- the ones in the villages are moving to the city, the ones in the city are moving to bigger cities and the ones in bigger cities are leaving the country. The situation is not different in developed countries like the US and UK HCW’s move from rural areas to cities (even though their rural areas are more like our cities). However, what these countries have done in areas where there is a shortage of HCWs is to upskill individuals in the community e.g. birth attendants to do the job. This training includes ability to promptly identify those pregnant women who are likely to have complications e.g. PPH, Obstructed labour and refer appropriately. This is not an impossible task. To think that by some miracle we would suddenly have trained HCW’s in every camp, rural village is wishful thinking to say the least. What we need is innovative ideas on how to better use our TBA’s.

The first stage in the elimination of TBAs in Nigeria should be massive training of CHEWs as skilled birth attendants! They are indeed trainable to manage life threatening complications of pregbancy and childbirth. Thereafter, they should be incentivized to stay in rural areas. We should also provide health insurance cover for all pregnant women and pay TBAs for identifying and referring women in labour. If we do all these and provide much needed lifesaving commodities and basic equipment , maternal mortality in Nigeria will crash.

95% of deliveries will occur without any form of assistance or intervention in a pregnant woman. It is the 5% that causes all the difference in maternal mortality ratio that is the crunch. Skilled birth attendants recognise these 5% and offer interventions that reduce morbidity and mortality, while traditional birth attendants are lulled by the false confidence of satisfactory delivery of the 95% that would have delivered without any intervention. They are therefore unable to recognise these 5%, and plod on expecting good outcomes as previously.

The challenge is, how can you teach an old dog new tricks?

Best to reskill them for alternative careers and advice them to promptly refer. In the 779 local government areas in Nigeria, it will be disingenuous to assert that during 38-40 weeks gestational period, a pregnant mother cannot find a skilled birth attendant.

Head To Head

Are traditional birth attendants good for improving maternal and perinatal health? Yes

BMJ 2011; 342 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d3310 (Published 14 June 2011)Cite this as: BMJ 2011;342:d3310

1. Joseph Ana, former commissioner for health, Cross River State, Nigeria

1. jneana@yahoo.co.uk

Joseph Ana argues that the shortage of skilled health workers means traditional birth attendants have a valuable place, but Kelsey A Harrison(doi:10.1136/bmj.d3308) believes they do more harm than good

The use of traditional birth attendants has generated a lot of heated debate over the decades, especially among health professionals. But the facts strongly support their use.

All over Africa, governments are introducing (or announcing) free healthcare for pregnant women and children under 5 years in the rush to meet the United Nation’s millennium development goals on reducing maternal and child mortality. Maternal mortality in sub-Saharan African countries varies widely, ranging from 800 to 2500 per 100 000 live births. Infant mortality ranges from 100 to 150 per 1000. Surely, all trained health hands must be on deck to deal with this emergency, including the hands of trained and monitored traditional birth attendants? Not to do so is unethical.

The causes of the poor health outcome for pregnant women and children are many, but the most important reason is the severe shortage of trained and skilled health workers. In some countries fewer than 20% of births are attended by skilled health workers.1 The problem is worsened by health …’

TBA should be discouraged and their should be a law to guide against the practice.

Sensitization is also required at the communities and PHCs especially during immunization activities.

I read with much interest this great piece by Chibuike Alagboso on Traditional Birth Attendants in Nigeria and I would like to add my opinion to this interesting debate. The author has brilliantly presented the facts and has asked a very valid question of whether the government should direct its effort and resources towards the training TBAs as a stopgap measure or focus on initiatives that will improve access to healthcare for all women.

My view is that TBA’s are a great asset to the community. Harrison and colleagues (2004) have defined ‘assets’ as the collective resources which individuals and communities have at their disposal, which protect against negative health outcomes and promote health status. Foot and Hopkins (2010) have suggested that community assets can include among others; the practical skills, capacity and knowledge of local residents and the resources of public, private and third sector organisations that are available to support a community. Asset based approach for improving health is not a new concept and has been used all over the world by many different communities. How might we take this approach forward? Morgan and Zigilo (2007, 2010) emphasise the importance of asset mapping as a starting point. Assets in this case would be TBA’s. Mapping will also help to identify the most appropriate ‘asset indicator’ to be used in evaluation of the performance of trained TBA’s in the community.

Training these unskilled (TBA’s) but important workforce (assets) as currently happening in many communities as described in Chibuike’s paper is the best way forward. We just need to be smart regarding how we regulate, measure and monitor the activities of TBAs. Evidence of effectiveness of this approach could come from small case studies and small scale exploratory research. Much work still needs to be done.

Yes, TBA’s may in part have contributed to the increase in maternal mortality in Nigeria as alluded by the Chief epidemiologist in the Federal Ministry of Health, but to think that we can exclude them in the fight to reduce maternal deaths is foolhardy. Therefore to answer Chibuike’s question, I believe our government should embrace TBAs as community assets whilst striving to improve access and quality of healthcare provided in statutory healthcare services.

References

•Foot J, Hopkins T. A glass half full: how an asset approach can improve community health and wellbeing. Improvement and Development Agency, London; 2010.

•Harrison D, Ziglio E, Levin L, Morgan A. Assets for health and development: Developing a conceptual framework. European Office for Investment for Health and Development, Venice, World Health Organization; 2004.

•Morgan A, Ziglio E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: an assets model. Promotion and Education 2007; 14:17.

•Morgan A, Davies M, Ziglio E. Health Assets in a Global Context: Theory, Methods, Action. Springer, London; 2010.

Thank you Dr. Opko for your comments. As outlined in the article, the TBAs that were discussed were in a conflict area. The article opens with the delivery of a baby in a forest while the mother was escaping from insurgents. In these circumstances, the mother would have been in a very fragile physical and mental state and the TBA was nearby at that moment. The presence of a skilled birth attendant would have been ideal in the circumstances.

Away from conflict zones, TBAs are found within many communities and there are many reasons pregnant women opt for them, even when there is a primary health facility in close vicinity. These reasons may include their lower cost or more flexible payment options, the familiarity with the TBA and the possibility of giving birth in a more friendly environment. More investment in training the TBAs could be a way to improve their skills and the outcomes of pregnant mothers.

This article is great. It is a great challenge for delivery specialist like midwives to operate in “Hospitals with out walls” like IDP centers where there are great needs for them than remaining in hospital with walls and doing nothing or a little

It is clear from the data that our primary and tertiary health centres are unable to manage the sheer volume of births that happen in the country. The only sensible solution is to pull TBAs into the formal healthcare system by training the, collecting data from them and also learning from them. I find it so interesting that women choose to use TBAs not just because of the lower cost but also because of the way they are treated. Primary health centres have to do better in terms of respect and cost if they want to woo women to use their facilities for giving birth.

Personally, I believe pregnant women patronise these TBAs mainly for two reasons – ignorance and poverty. I don’t think the dearth of skilled health workers is the reason. Let the government offer free maternal healthcare and let’s watch the tide change. Universal health coverage is the answer!

Great Article.When you are poor the only available option seems like the best option.Elites tell the difference from delivering a baby in Nigeria and another in US or UK.TBAs are patronized because they are the only option.The cost of healthcare at govt hospitals and TBAs is close or equal.Butvthe fashion in which it is collected is the catch.You can pay some and pay the rest later.In the hospital u pay before delivery.The hidden cost of transport,waiting time and bureaucracies that can be avoided and even language barrier makes the TBas acceptable. Beneath it all is poverty and education.This needs to be tackled from its roots.TBAs friend or foe……it is just another business.