By Ibukun Oguntola and Onyinye Oranezi (Lead Writers)

Emergency Operations Centres, first used in Nigeria during the national polio response, were valuable assets in Nigeria’s polio response, and they continue to be a vital resource now. Transitioning Polio EOCs into public health EOCs will help boost efforts to strengthen Nigeria’s national and subnational health security.

Many of the tools and resources used in Nigeria’s successful fight to end wild poliovirus (WPV), were also used in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic and other infectious disease outbreaks like yellow fever. Emergency Operations Centres (EOC) where data collection and response to public health threats are coordinated, are one of such resources.

Nigeria has reported over 20 public health emergencies and infectious disease outbreaks between 2016 and 2018; the country is one of five member states in the World Health Organization (WHO) African region to report five or more public health events annually. These public health emergencies often occur concurrently, necessitating multisectoral coordination. EOCs help to improve information sharing as well as joint programming for better management and coordination of activities during public health emergencies.

Establishing polio EOCs

Ten years ago, Nigeria accounted for more than half of all polio cases globally. Ten years later, the story is different as through coordinated and dedicated action at all levels of government, collaborations with Civil Society Organisations (CSO), and the commitment of health workers, the nation eradicated WPV and was certified WPV-free in August 2020.

Polio EOCs, first used in Nigeria during the national polio response, played a vital role in the eradication efforts as they helped spur greater action towards polio eradication, coordinating the national polio response including, data collection, collaboration between sectors and units, and real time information sharing.

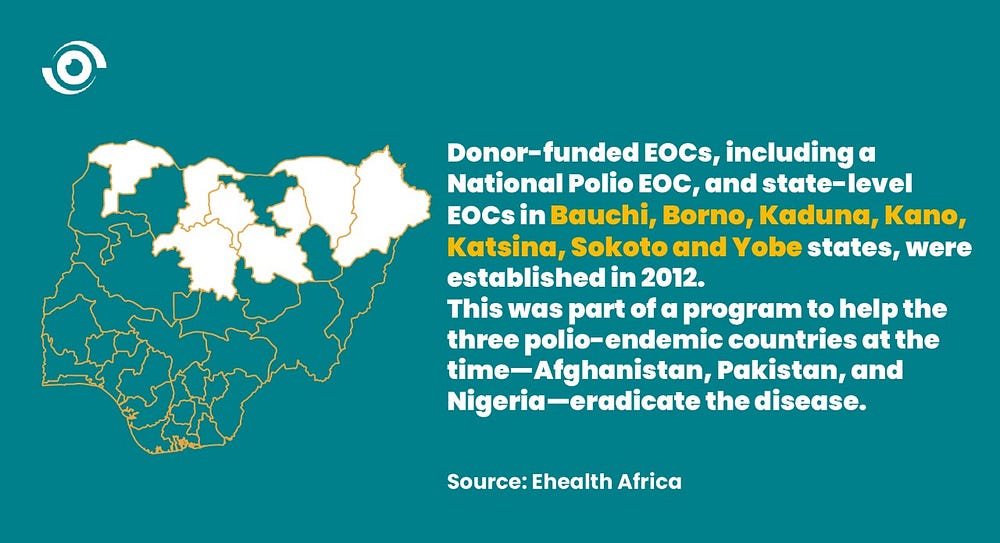

Nigeria developed a National Polio Eradication Emergency Plan in 2012, but a lack of proper implementation resulted in an increase in the number of children paralysed by the poliovirus from 21 in 2011, to 122 in 2012. As part of a programme to help the three polio endemic countries at the time — Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nigeria — eradicate the disease, donor-funded EOCs, the National Polio EOC, and state-level EOCs in Bauchi, Borno, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Sokoto and Yobe State, the 7 states with the highest burden of polio cases, were established in 2012.

With the establishment of the EOCs, there was improved implementation of the National Polio Eradication Emergency Plan. The Polio EOC system ensured that polio response functions were centralised, and that state-level polio operations were strategically aligned with the national polio programme and the priorities of the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA). The EOCs were critical in developing and executing eradication strategies, improving vaccination campaigns, and coordinating outbreak response. The Borno — Yobe Strategic Operational Plans of 2014 also contributed to a significant reduction in the number of children paralysed by polio — by 57% and 90%, respectively.

Establishing public health EOCs

Recognising the value of developing national capacity to coordinate Nigeria’s outbreak response, in 2017, the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), established a National Public Health Emergency Operations Centre (PHEOC). PHEOCs are quite like Polio EOCs, the only difference is that they provide a platform from which to coordinate all public health emergencies.

In 2018, in collaboration with the respective state governments, the NCDC began the process of establishing subnational PHEOCs and as of March 2021, PHEOCs have been established in 28 of Nigeria’s 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT); 10 of which were established during the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach contributed to the effective COVID-19 response in Nigeria allowing for coordinated risk and crisis communication, as well as efficient resource management.

State governments must commit to investing in transitioning polio EOCs into full PHEOCs and provide the necessary support to sustain them as they can improve subnational capacity to prevent, detect and respond to future public health emergencies and effectively contribute to strengthening our national health security.

Transitioning polio EOCs into PHEOCs

Nigeria’s polio EOCs — alongside the ones established in Afghanistan and Pakistan — were among the first centers established in developing countries. They were valuable assets in the polio response then and continue to be a vital resource now, particularly as Nigeria works to strengthen its national and subnational health security. Converting them into state PHEOCs can help boost health security at the subnational level, and so putting less pressure on the national PHEOCs during disease outbreaks.

Emmanuel Benyeogor, Subnational Support Officer at the NCDC said the NCDC is working to build the capacity of erstwhile polio EOCs so they can become PHEOCs, he however indicated that there are some factors slowing down the process. “One major challenge is the sustainability of the transitioned EOCs once the donor funds go.”

The concerns are valid as once a polio EOC transitions into a PHEOC, it will no longer be funded by the polio programme. But the successes of the polio EOCs have demonstrated the key role that the establishment of subnational PHEOCs can play in disease outbreak response. In addition, health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic have shown the importance of having adequate systems to respond to public health emergencies. State governments should therefore commit to, not only investing in transitioning vertical structures like polio EOCs into full PHEOCs, but also providing the necessary support to sustain them, as they can improve subnational capacity to prevent, detect and respond to future public health emergencies and effectively contribute to strengthening our national health security.