By Oluoma Omeje, Joy Uzoho, Patience Adejo and Abdulmajeed Abdulsalam (Lead Writers)

In February 2023, the Director General of the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA), Professor Mohammed Sambo, inaugurated a committee to develop the NHIA Operational Guidelines. As the committee works to meet the 4-week deadline they have been given, here are learnings from Ghana and Rwanda’s health financing mechanisms they can leverage to develop the guidelines and address the gaps in achieving UHC in Nigeria.

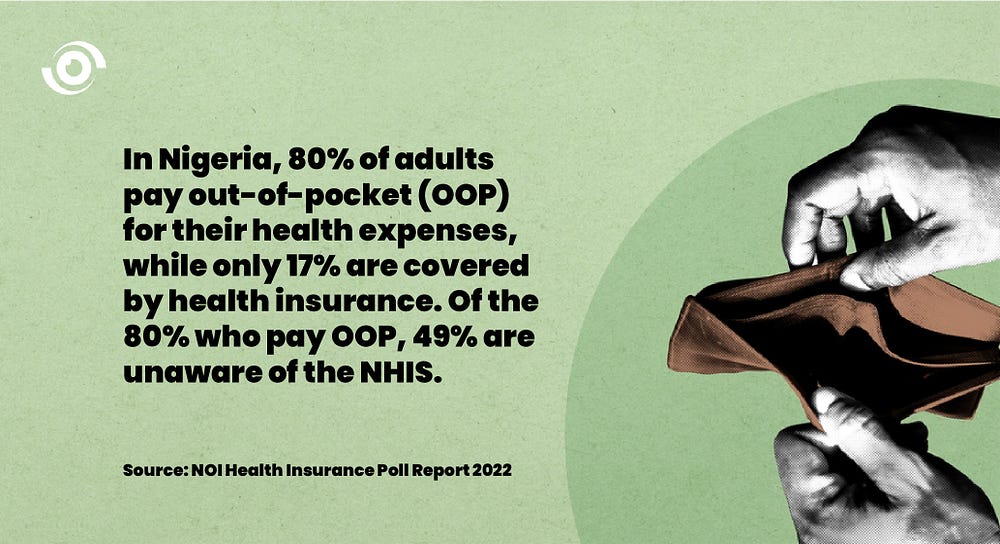

Financial risk protection — ensuring that all people have access to quality health services without financial hardship — is critical to achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC). However, despite initiatives designed to protect Nigerians from financial hardship, first the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 2005 and then the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) Act in 2022, a survey by NOIPolls revealed that 80% of adults pay for their health out-of-pocket, and only 17% have health insurance cover.

Health Insurance in Nigeria based on the NOIPolls survey

Out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditure can cause financial hardship by forcing people into an ‘either/or’ situation in which they are forced to choose between health expenditure and another equally important need. According to a further breakdown of the NOIPoll’s survey, of the 80% of the adults who pay OOP for their health expenditure, 57% are willing to pay money monthly or yearly for health insurance. Similarly, 49% stated that they were not aware of the NHIS.

These findings suggest that despite the provisions in the NHIA to provide financial hardship protection, access to health insurance may be a major issue across the country.

Health financing in Nigeria: The Journey so far

The history of health financing in Nigeria dates back to 1962, two years after Nigeria’s independence. During that time, the government funded universal and free healthcare particularly in the public health facilities, using funds from general revenue, especially oil exports. Unfortunately, this was short-lived and was phased out following the global slump in oil prices in the 1980s when the government could no longer afford to fully cover the cost of care. In a bid to mitigate against the dwindling funding for healthcare, amongst other pressures, in 1999, the National Council on Health approved and signed legislation revamping the health financing model to ensure full private sector participation in what became the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS).

When the NHIS was launched in 2005, its goal was to ensure “universal coverage and access to adequate and affordable healthcare in order to improve the health status of Nigerians, especially for those participating in the various programmes of the Scheme”. In May 2022, the NHIS legislation was replaced by the NHIA Act. Among other things, the Act makes health insurance mandatory for every Nigerian and legal resident, to promote, regulate and integrate health insurance schemes in the country. It authorises the NHIA to improve and leverage private sector participation in the provision of healthcare services.

According to the Act’s provisions, all citizens are required to be covered by health insurance schemes; however, vulnerable people are exempted from contributions under health insurance. As a result, contributions will be made on their behalf by one or a combination of the three tiers of government, development partners or non-governmental organisations. The Federal Government contributes to funding for vulnerable people through the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF).

In February 2023, nine months after the Act was signed into law, the Director General of the NHIA inaugurated a committee to develop the NHIA Operational Guidelines which will help accelerate the implementation of the NHIA Act. The committee, which has been given four weeks to complete the task, should consider incorporating lessons learned from countries such as Ghana and Rwanda, which have made significant gains in health insurance coverage and are well on their way to achieving Universal Health Coverage.

Learnings from Ghana and Rwanda

Ghana’s health financing mechanism evolved from a tax-funded system prior to independence to community-based health insurance (CBHIS) in the 1990s and finally, the establishment of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 2003. Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) was established with the goal of providing a wide range of healthcare services to Ghanaians through district mutual and private health insurance schemes, as well increasing affordability and utilisation of drugs and health services in general, and particularly among the poor and most vulnerable populations. It is financed from three sources including:

- Value-added tax on goods and services: 2.5% of which is known as the National Health Insurance Levy (NHIL) accounts for approximately 74% of revenues

- An earmarked portion of Social Security Taxes and the National Insurance Trust (SSNIT): accounts for approximately 20% of revenues

- Individual premiums account for up to 3%, while funds from investment returns and others such as parliaments and donor account for the remaining 3%

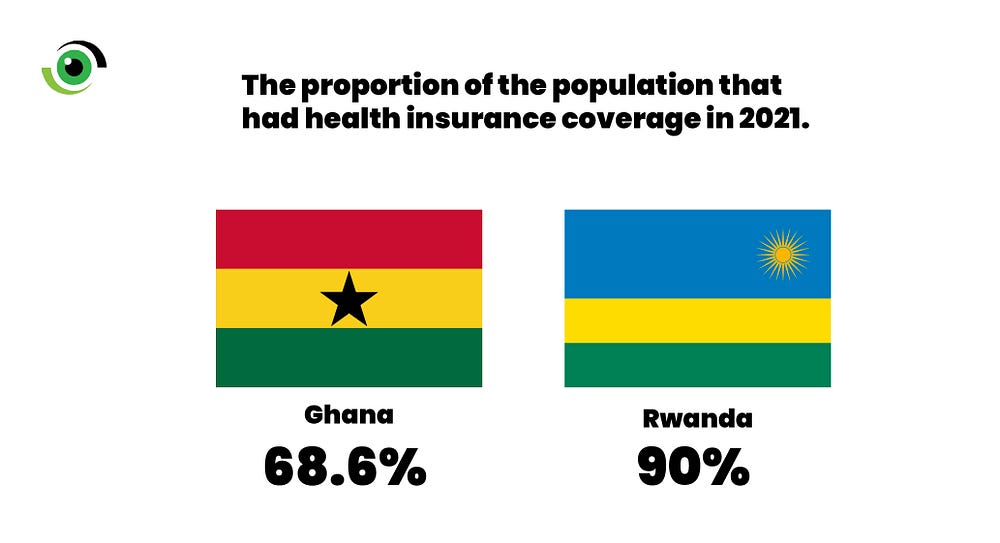

All Ghanaian residents (including non-citizens) are eligible for NHIS coverage. However, two-third of NHIS enrollees are exempted from premium payments — for instance, SSNIT contributors, enrollees under 18 years or over 70 years as well as indigent people, institutionalised people and beneficiaries of social protection programmes may not pay premiums. As at 2021, 68.6% of the Ghanaian population were covered by either NHIS or private health insurance schemes

.

Rwanda’s progress is primarily linked to the successful implementation and national scale-up of CBHI for the informal sector. The CBHI has enabled Rwanda to have approximately 90% of its population covered by health insurance. Secondly, high coverage of health insurance boosted access to essential Primary Health Care services and is thought to have contributed to Rwanda’s achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal three. Membership in the CBHI scheme is accessible to working-age Rwandans in the informal sector. This is made possible by a one-time contribution fee per household member and a 10% co-payment fee for all services at the healthcare facilities. This fee varies according to the household’s income category.

These examples prove that political will and commitment are key to designing and implementing mandatory health financing policies, and that it’s possible for countries to successfully invest in affordable social health protection for members of the informal economy.

Taking Nigeria’s NHIA forward

To strengthen the implementation of the NHIA Act, the government can take the following five actions:

(1) Progressively scale-up coverage to the informal sector

There is a tangible difference between having a general awareness of NHIA’s existence and concrete knowledge of how it works, how to enroll, and what services are available to enrollees. To provide this information and enroll people on the spot, the government could set up health booths in public and religious areas such as large markets, highly populated churches and mosques and popular malls. It could also work with organised informal sector associations, such as the trader’s union, the union of road transport workers, etc., to roll out comprehensive education campaigns that provide accurate information about health insurance and enrolment.

(2) Establish and strengthen measures to enforce the mandatory legislation

While sensitisation of the public, especially informal sector groups who can pay a premium, is key, the NHIA must put in place measures to tackle non-adherence among citizens to the mandatory law within a set timeframe (for example 12-18 months). Health insurance enrolment chould be made a prerequisite for assessing other government services that are often needed by people who can afford the NGN15,000 annual premium, such as drivers’ licenses and international passports, vehicles and company registrations, etc. In addition, as the Bank Verification Number (BVN) now makes it possible to identify an individual’s total account balance even if they have multiple accounts, an annual deduction of premiums can be made statutory on all bank accounts of unenrolled citizens that meet a set minimum balance (e.g., NGN500,000). Implementation of these recommendations will however need a robust plan to mitigate potential unintended consequences related to equity. For example, the number of dependents for every individual operating a bank account varies which can make premium affordability determination based solely on bank account balance inequitable.

(3) Define clear approaches for funding the vulnerable group fund

While the NHIA has listed a couple of sources for covering the 133 million vulnerable Nigerians, including the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), health insurance levy and voluntary contributions, it might be worth including coverage of a set number of people in states annual budget allocations as well as mandate states to make an equity contribution of 1% of their Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) to ensure that the amount of funds available to cover these groups can be better forecasted or predicted.

(4) Strengthen service delivery to boost population confidence in the scheme

A key challenge to health insurance coverage has been the lack of trust in the scheme due to poor quality health services delivery. It will be important for the NHIA to map out steps for monitoring and improving the quality of services at all empanelled facilities and equip them with clear systems to communicate client satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

(5) Strengthen State Health Insurance Agencies (SHIA) in all 36 states and help them enforce the mandatory Act

All SHIA are required to comply to the requirements of the NHIA Act including the compulsory enrolment. NHIA can establish a functional routine problem-solving and knowledge exchange platform to enable cross-learning of best practices among the various SHIAs and to brainstorm solutions to enrolment and other scheme-related challenges in a timely manner.

By applying these recommendations and learning from other countries, Nigeria can achieve universal health coverage by 2030 and ensure that no one is left behind. However, the government must intensify efforts to address the urgent need for increased sensitisation to educate the Nigerian people about the National Health Insurance Authority’s existence, as demand generation is critical to the implementation of mandatory health insurance.

Joy Uzoho is the Senior Consultant, Health Systems and Financing at Options Consultancy Services Ltd.