On December 12th, 2023, key health sector stakeholders gathered at the presidential villa to commemorate Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Day. This culminated in a historic event: the signing of a new health sector renewal compact by all relevant stakeholders, including the federal and state governments, donors, and development partners. This is the first Sector-wide Approach (SWAp) in the health sector in Nigeria, introduced by the Coordinating Minister for Health and Social Welfare as key to increasing transparency and accountability in the health sector.

On the same day, the Lusaka Agenda was launched. The agenda includes recommendations from the Future of Global Health Initiatives (FGHI) process, which sought to provide recommendations for the evolution of Global Health Initiatives (GHI), by drawing on lessons from country-focused initiatives such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, and Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), and others. It lays a “path towards a joint, long-term vision of domestically financed health systems and UHC that leaves no man behind.” It highlights five key shifts for the long-term evolution of the GHI ecosystem, the first two of which are for GHIs to “make a stronger contribution to primary health care by effectively strengthening systems for health” and “play a catalytic role towards sustainable, domestically financed health systems and public health functions.”

These shifts highlight the need for GHIs to align with one national plan in the countries in which they operate, invest in resilient health systems, and align with the goal of programmatic and financial sustainability by supporting increased domestic spending on health. This, essentially, is what the new Nigeria health SWAp is looking to achieve — align resources towards building a more effectively coordinated, resilient public health system.

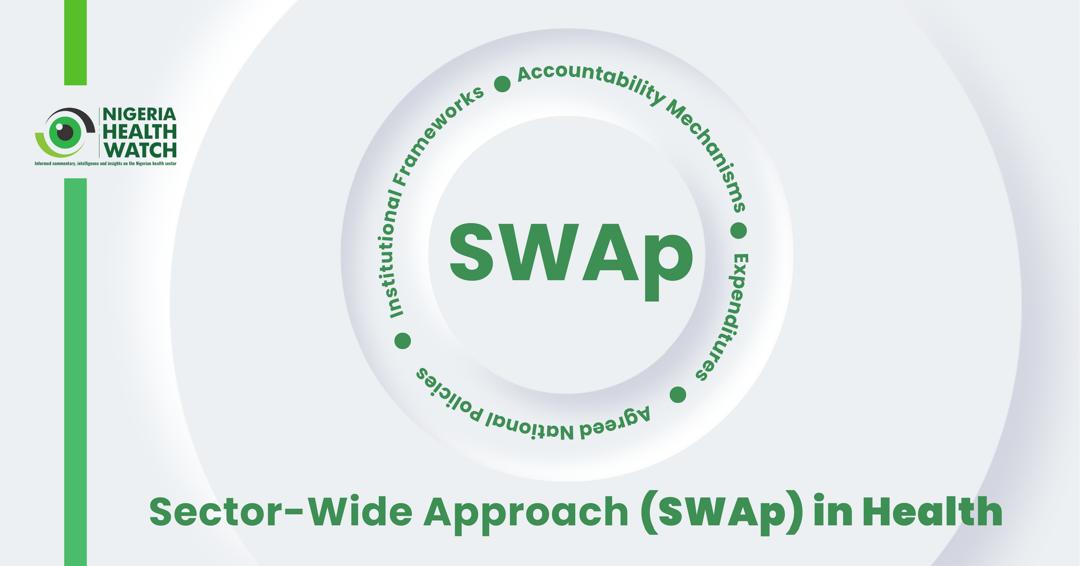

What is a SWAp?

A SWAp is an aid delivery mechanism whereby national governments lead the partnership, and all funding is directed toward supporting a set of national policies through common management systems guided by agreed policy, expenditure and institutional frameworks, as well as strong accountability mechanisms. In a SWAp, all donors align with a common framework and national policy in exchange for the inclusion of their policy/programme objectives/priorities in the national health programme and an input in how resources are allocated.

“Alignment is the word that’s popular nowadays, akin to what SWAp was. We use different languages for it. But how can we align better? And so, the Ministry empowering itself to make demands on these development partners is definitely one way to move forward, persuading governments that they don’t have to say yes to everyone, that they can say “no, we don’t want that, we want this” is doable. Oh, these financiers want to move their money, right? And the government can demand to be in the driver’s seat. But in return, it has to do so credibly”. — Julie McLaughlin, World Bank (rtd), Consultant with UNFPA, The Global Fund, etc., on all things related to the Alignment Agenda.

SWAps require institutional and expenditure frameworks that clearly outline the policies and institutional arrangements that will deliver improved health outcomes and UHC, as well as strong accountability mechanisms. According to McLaughlin, SWAps do not solve for a quality set of strategies, policies, and expenditure programs, and this is what resulted in the failure of many early SWAps. It is an “approach”, a way of doing business. Without the right content, it will fail to achieve its objectives.

Historical Precedents: Why SWAps?

“I will tell you that before 1990, nobody used the phrase health systems” Julie McLaughlin said. “They didn’t talk about health systems. I have ancient PowerPoints that PowerPoint won’t let me open anymore, that have titles like “Health Systems and Malaria,” “TB and Health Systems,” “Immunisation and Health Systems,” and “Integrated Childhood Management and Health Systems.” That is what I was almost on parade doing, trying to convince everybody that what we really needed to do was focus on the glue that holds everything together, not the individual inputs…. now, that’s the norm. It’s the global fund for disease, as people call it, but that wasn’t the case then. And so, it’s those things, combined with what had been a nagging recognition for quite a while — development assistance wasn’t sustainable, wasn’t having a sustainable impact. It wasn’t owned, government being in the driver’s seat.” Julie McLaughlin added.

In simple terms, aid delivery mechanisms such as SWAps emerged in response to decades of frustration with fragmented, duplicated, and poorly targeted aid programmes and with the aim of improving aid effectiveness. Development Assistance for Health (DAH) has historically been driven by donor interests rather than recipient needs, focusing on reducing the spread of infectious diseases that could spread to their countries or advancing their economic or political interests. This has resulted in vertical and parallel programming, limiting the availability of resources (funding, human resources for health, etc.) for wider health system strengthening, which is required to improve population health outcomes.

Nigeria’s complex health policy landscape: Is a SWAp the answer?

In Nigeria, fragmentation, poor coordination, and weak governance are all factors that affect the effective implementation of health programmes and policies. The Nigerian health policy landscape has seen a few attempted reforms, ranging from the Saving One Million Lives project (launched in 2012 by the current Minister of Health and Social Welfare when he was the Minister of State for Health) to the 2014 National Health Act, which established the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF).

Health policies have historically been difficult to implement in Nigeria, with the journey to legislation fraught with challenges such as a lack of political will and, after passage and approvals, poor implementation (largely due to poor leadership and governance and a lack of funding) and subsequent discontinuation when political administrations change.

“Nigeria, of all places, should be doing this because of its heft, because of its global clout, and because of its indicators in the health sector, right? Both its financial and financing indicators and its outcome indicators”. — Julie McLaughlin.

Having a unified approach and framework for the development of a national health system into which public and donor resources can be channelled will ensure adequate resources, improve coordination, and reduce inefficiencies, but this will require strengthened governance and effective public financial management and accountability mechanisms.

So why has Nigeria never had a SWAp?

Celades thinks this is due to two reasons: Nigeria’s highly decentralised healthcare system makes instituting a SWAp particularly challenging, and secondly, the country’s weak Public Financial Management (PFM) system. To successfully implement a SWAp, Nigeria has to overcome these two challenges, which, according to Celades, similar countries have been successfully done.

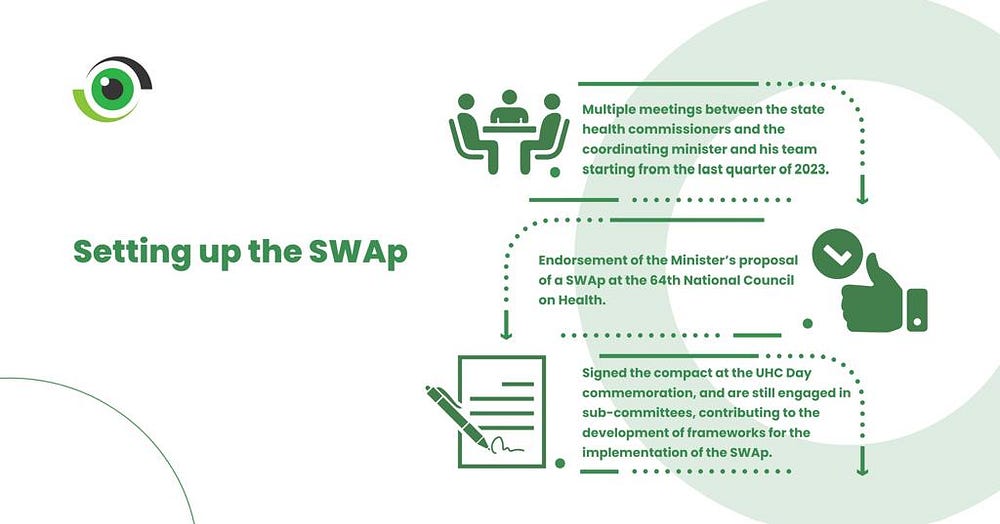

Setting up the Nigeria health SWAp: sub-national level involvement and implementation outlook

The Nigeria health SWAp development process included multiple stakeholder consultations and engagements with all parties, including sub-national governments/state health commissioners, according to the commissioners for health of Ekiti and Rivers states, Dr Oyebanji Filani and Dr Adaeze Oreh. The state health commissioners have had several meetings with the Minister and his team starting from the last quarter of 2023, endorsed the Minister’s proposal of a SWAp at the 64th National Council on Health, signed the compact at the UHC Day commemoration, and are still engaged in sub-committees, contributing to the development of frameworks for the implementation of the SWAp.

On the outlook for sub-national implementation of the SWAp, the goal is an equitable distribution of resources across the 36 states and the FCT, to ensure that no state is left behind. Where donors and development partners have previously directly engaged with and fund state programmes, based on their areas of interest and priorities, this will no longer be the case. The government will now determine where resources go, based on need and potential for maximum impact on population health outcomes.

According to Eduardo Celades, Chief of Health at UNICEF Nigeria, while their main approach is to work with country systems, the SWAp necessitates a rethinking of their implementation model, especially at the subnational level, where UNICEF has multiple Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) with sub-national governments, across 14 states, as well as strengthening the vaccine supply chain to the last mile to meet the mandate of improving maternal and child health outcomes.

“Maybe from UNICEF, it is likely that it will be needed less for implementation but more for capacity building. But we can continue to strengthen and create capacity to really monitor. So, we see ourselves evolving from service delivery or primary implementation towards technical expertise. This is how we think we are going to move”. Eduardo Celades said.

UNICEF is committed to reducing inequities in the delivery of healthcare across geographical regions, between and within states, including addressing rural-urban inequalities. UNICEF hopes that the SWAp, would result in a high-quality package of health services, delivered to women and children across Nigeria.

Now there’s a SWAp, What’s next?

Now that the compact has been signed and the health sector’s policy framework, the four-point agenda, has been unveiled, next step is to develop an implementation framework that includes expenditure, monitoring, evaluation and accountability frameworks. Specifically, experts want to see three main things happen in the near to intermediate term:

- A code of conduct: A code of conduct specifies what each party and signatory to the compact brings to the table, what success looks like, what core indicators will be used to measure success and how parties will be held accountable. Since SWAps are intended to reduce inefficiencies, it is important that parties agree and align, so that government can focus its resources on one framework, as opposed to having to align to multiple donors’ frameworks and processes. Experts also recommend that all parties be evaluated on adherence to the code at every joint annual review, using scorecards.

- An assessment of needs, assets and resources available at the sub-national level: The starting point for ensuring a successful implementation of the SWAp at the sub-national level is clarifying what is available at the sub-national level and identifying areas of need, so that resources can be directed towards areas of greatest need.

“At the sub national level, we should be interrogating the institutions and the assets or resources which the state currently has. So, we’re looking at what’s the existing leadership structure, what’s the financing like in terms of state government support for critical areas in health? What’s that ecosystem financing looking like at the state level? What’s the human resource for health at the state level? What’s existing? Because it’s one thing to say funding is coming to support certain programmes, but then what do you have on hand because we should be careful that this doesn’t turn out to be one of those “funding is coming down” and it’s only going to where the partners say it should go”. Dr Adaeze Oreh, Honourable Commissioner for Health, Rivers State.

- Financial transparency: It is imperative that the flow of resources be visible, both at source and at delivery points. Learning from the implementation of the BHCPF, clarity on what funds are being used for at service delivery points is key to strong accountability, highlighting the urgent need to strengthen the country’s PFM systems. State governments need to become more transparent about how resources are allocated, disbursed and used as they work towards meeting their financial commitments to the pool.

As we continue to delve into the complexities of healthcare reforms, it is important to understand the policy direction in the health sector. In order to get different points of view, you can look forward to a follow-up article which will include perspectives from civil society organisations and private sector health providers, ensuring a diverse range of insights into the challenges and opportunities ahead.