Editor’s Note: This week’s Thought Leadership piece comes from Dr. Ibrahim Mamadu, Health Emergencies Programme, WHO Nigeria. He asks whether Nigeria is prepared with its population of 200 million people to detect, respond and prevent possible epidemic outbreaks and analyses what the country needs to do, to guarantee the health security of the population.

I love movies, especially fantasy and science fiction films based on true stories. Growing up, one thing that I could always remember from movies, were the underlying themes. My friends could recite lines from great Westerns like The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; lines like “When you have to shoot, shoot; don’t talk” said by the great bandit Tuco. They could also recite lines from movies flawlessly, like The Godfather or The Last Don.

What I could remember, however, were the trends, themes, subthemes, and plots. I was enthralled by the 90’s movie Outbreak, where a virus carried by a monkey caused a deadly human outbreak faraway on another continent. In the blockbuster movie Mission Impossible 2, a virus weaponised by terrorists “Chimera” threatened a large proportion of the world’s population; in World War Z, a virus caused a global zombie apocalypse, while in The Day After, a nuclear detonation wiped out most of humanity. These memories perhaps shaped my world view and towards my chosen profession — public health and global health security. I have always been one to ask the “what if” question, imagining the worst-case scenario.

In 1918, an influenza virus, caused by an H1N1 virus that initially only infected pigs was found in birds and later in humans. It then spread rapidly from person to person. By the time the outbreak ended, about a third of the world’s population had become infected with the virus, leaving over 50 million people dead. That was the Spanish flu outbreak, the deadliest viral outbreak in recorded history. At the time, as travel around the world improved and became faster, the world got smaller. This provided ample opportunity for viruses and bacteria to spread to new populations not previously exposed to them, populations that had almost no immunity to the diseases these viruses caused. There was hardly collaboration between countries at the time — this was before the era of the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations (UN). All these conditions made it ripe for a perfect global pandemic, like the Spanish flu.

The world has changed a lot since then. Modern medicine gave us penicillin due to Fleming’s laboratory accident which has given rise to several generations of antibiotics. We developed vaccines and have even used them to eradicate infectious diseases like smallpox. We have a great country coordination system in the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other global and regional organisations. We now have access to a wider choice of communications channels to disseminate information, enabling us to keep the public informed about measures they can take to prevent the spread of infectious diseases.

So what has increased the risk of infectious disease outbreaks? Well, faster air travel means that it may take a new flu virus as little as 36 hours to spread from one side of the world to the other. The world’s population has exploded to nearly 8 billion, driving us further into previously uninhabited locations. This has increased our direct contact with animals through hunting, trapping, and farming. Urbanisation has made the phenomenon of crowded megacities ever so common. This increases the chance of human-to-human transmission of diseases. Imagine how easy it is for someone to sneeze on you in Balogun Market in Lagos or Garki Market in Abuja and infect others with a flu virus.

With overcrowding and poor town planning has come the problem of overstretched water, hygiene and sanitation facilities, making it more difficult for people to carry out simple hygiene practices like handwashing with soap or using a flush toilet, even in places that should be very clean such as hospitals.

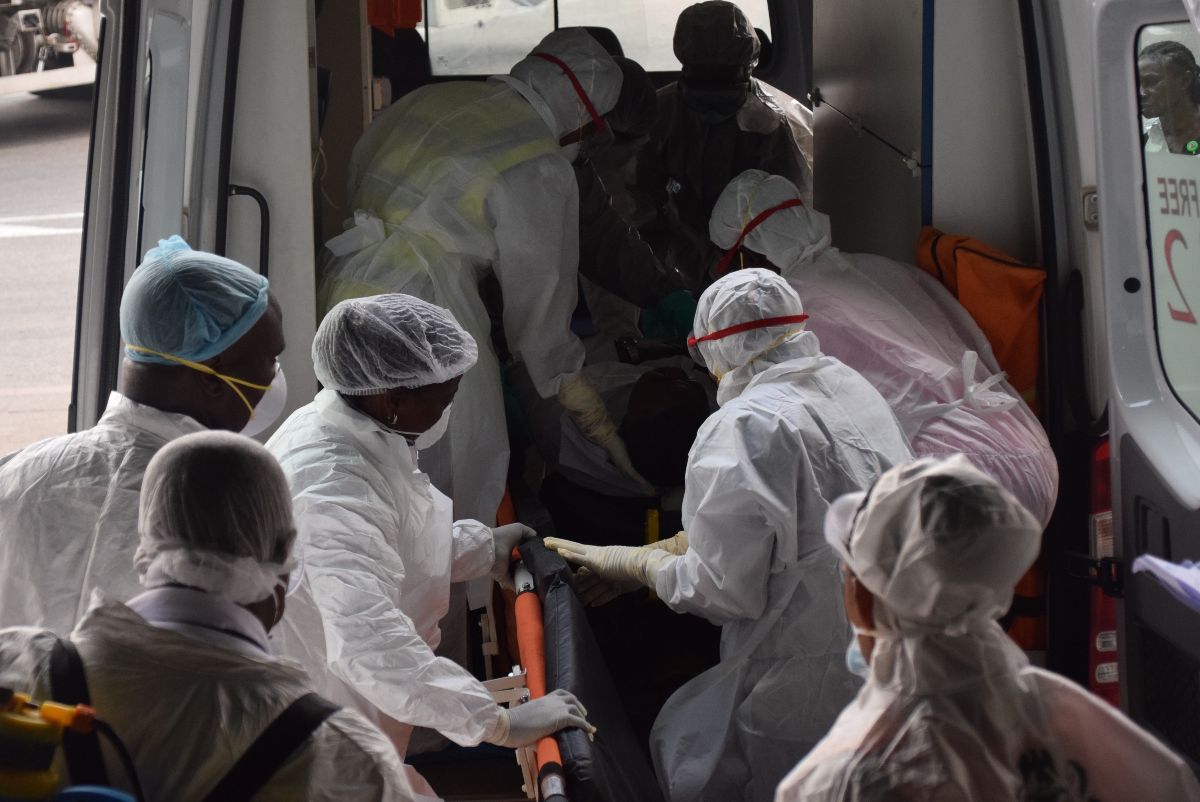

These and other new and emerging risk factors have made the world extremely susceptible to major global disease epidemics. And they have been happening! In 2009, an outbreak of H1N1 was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) as mandated in the International Health Regulations (IHR) and so enabling more global resources to be dedicated to the response. H1N1 was also believed to have started in animals and spread to humans. In 2014 the bats that carried the Ebola virus previously unknown in West Africa had devastating consequences in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone and causing the largest Ebola outbreak the world had seen.

So I always ask myself, what if a virus jumps from a grasscutter (or bush meat as it is popularly called in Nigeria) through a cut in the hunter’s hand during skinning or preparation and starts infecting humans in large numbers in Nigeria? Would this country of over 200 million people be able to detect, respond and contain this new threat?

The answer to those questions lies in the World Health Organisation (WHO) IHR 2005 requirement for countries to strengthen core capacities in their health systems. Under the IHR, which is a legally binding agreement signed by 196 countries and state parties, it is required for every signatory, including Nigeria, to strengthen their ability to prevent, detect and respond rapidly to any and all public health hazards. The principle is to contain these hazards at source and transparently report them to WHO and other countries on the situation. This is done through the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (IHRMEF) and four critical components are instrumental:

1. The State Party Annual Reporting: A mandatory practice by countries to self-report annually to WHO and the rest of the world on the status of their capacities in areas like surveillance, preparedness, laboratory, zoonotic diseases, human resources, Points-of-Entry, radiation, and chemical events, to name a few.

2. The Joint External Evaluation (JEE): To conduct the Joint External Evaluation (JEE) of the country’s capacities to prevent, detect and respond to public health hazards. This opens up the country to external evaluators who are subject matter experts, to critically assess the country’s self-reporting of its capacities every four or five years. Once consensus is reached on the country’s scores in the core capacities the assessors propose recommendations to improve them.

3. Simulation Exercises (SIMEXs): Countries are to perform simulation exercises which create a scenario of an event like the outbreak of Ebola and test the effectiveness of all the country’s capacities, plans, processes, people, and equipment in areas like airports, land borders, the surveillance system, and the laboratory systems. This can provide insight into the areas that need improvement.

4. After Action Reviews (AARs): These happen after an outbreak or event. This is a workshop or meeting of all relevant stakeholders drawn from sectors like health, agriculture, and environment, to assess the preparedness and response to a just-concluded outbreak. This helps to identify best practices, what wasn’t done so well and learn why they didn’t go well in detail. The recommendations from this will then be used to build capacity to improve responses to future events.

In Nigeria, these components have been implemented with some success, led by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), Nigeria’s national public health institute and the National Focal Point (NFP) institution under the IHR. Nigeria has consistently, and on schedule, submitted the country’s annual self-reporting on IHR capacities to WHO. In 2017, Nigeria conducted her first Joint External Evaluation (JEE), supported by WHO and other partners; shortly afterwards, a National Action Plan for Health Security (NAPHS) was developed, using the recommendations from her JEE to improve core capacities in 19 technical areas cutting across sectors like health, agriculture, environment, radiation, finance and many others.

When the JEE was conducted in 2017, Nigeria had an average score of 39 %, highlighting gaps in the country’s ability to prevent, detect and respond to infectious disease outbreaks. Areas the country was commended to have performed reasonably well in, was the vaccine access and delivery system and the epidemiology training programme that was building the human resource capacity to respond to infectious diseases. JEE’s tend to be conducted every five years, however in November 2019, the NCDC conducted a mid-term review to monitor the country’s progress. The follow-up evaluation revealed that progress had been made in several areas, namely, the passage of the bill in November 2018 by President Muhammadu Buhari to establish the NCDC strengthened diseases surveillance through training, improved public health laboratory network in the country. Nigeria now has a average score of 46%.

In early 2018, with the support of key partners and stakeholders, the NCDC also conducted a large scale simulation exercise in Lagos to test the country’s response capacity to a yellow fever outbreak. The country has also conducted several After Action Reviewsto outbreaks it has experienced in the past few years. These include for recurring outbreaks like Lassa Fever, Yellow Fever, Cholera, Meningitis and to new and re-emerging outbreaks like Monkeypox.

Globalisation has tested the capacity of countries like Nigeria to control the spread of infectious diseases, bearing the brunt of communicable diseases, like other low and lower middle-income countries. High-tech solutions are not often the first priority, but strengthening health systems, local laboratory infrastructure and building a pipeline of scientists, programme managers, and epidemiologists must be given priority. This is contingent on sustained funding to protect the country’s health security.

With all of these measures, I am optimistic that Nigeria will continue to do more to boost preparedness to respond to events of public health concern. My hope is that the country will not wake up one day and, as with the movie “While You Were Sleeping,” discover that a virus or bacteria has emerged and affected a large section of the population because the country did not prepare. That would be disastrous and should keep us all constantly on our toes to prevent such catastrophe. Our future literally may depend on this.

Thanks for the WHILE WE ARE SLEEPING write up. According to the latest JEE report we have moved from NOT PREPARED to WORK TO DO. Nice to hear that we are making progress NATION. What is more important is breaking down this report to state and LGA performance…While at Federal level, we are HAHA: half-awake-half-asleep, most of the states are FAHA: fast-asleep-hardly-awake. at LGA level, nearly all are FANA: fast-asleep-never-awake

Indeed we have much work to do

I love when information is beautifully written. Well done.

How do we strengthen our local laboratories and primary health care system as a whole? Seeing that the health sector is becoming populated with health workers who are not safety conscious. Health workers who are more concerned with profit making.

I would recommend that every health worker should undergo trainings regarding how to respond to outbreaks at least twice a year. Especially the health workers in the primary health care units.

Nicely written, very well done.

Health Security is a matter of national security, and policy makers need to take this into consideration in order to make funds available, and sustain efforts aimed at preparedness as Dr Ibrahim has advocated for.

We have to prepare, there is no other choice.