By Kenneth Ibe and Onyinye Oranezi (Lead Writers)

Mrs Aisha Yunisa, a fifty-year old woman from Niger state, got married in her early twenties and was living happily with her husband and their beautiful daughter. When she started noticing patches of discolouration on the skin in her hands and legs, she thought it was a severe skin reaction and her husband took her to a nearby pharmacy which is their first port of call when they fall ill.

The medication from the pharmacy did not bring any relief, and eventually, the skin discolouration became painful skin lesions with early signs of some nerve damage. As her condition deteriorated, Aisha thought she had been poisoned and so, she sought herbal treatment. Again, nothing changed, rather things grew worse. At this time, her ‘chemist’ had started suspecting that it was leprosy and so he advised her husband to take her to Chanchaga Leprosy Hospital in Niger State for proper diagnosis and treatment, if confirmed.

They took his advice and went to the hospital. There, the doctors confirmed that it was leprosy and immediately commenced treatment. The treatment was successful however, the disease had already severely affected her limbs, and nothing could be done about her deformed hands, feet, and eyes. These deformities exposed her to a great deal of stigmatisation from everyone, including her co-wife.

Due to the stigma, Aisha divorced her husband and left Niger state for Alheri Community in Yangoji Village, Kwali Area Council in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The community is home to more than 500 people, most of whom are people affected by leprosy and their families. There, she met and married another man in the community who has also been affected by the disease.

Also known as Hansen’s disease (HD), leprosy is an ancient chronic mycobacterial infectious disease that is associated with serious morbidity. Although curable, it continues to be a disease of public health concern because of the stigma associated with it. Leprosy disease usually occurs after prolonged contact with an infectious person. It is passed from person to person via droplets from the nose and mouth during close and frequent contact with someone with untreated leprosy. Classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs), leprosy, if left untreated or not diagnosed on time, can cause progressive and permanent damage to the skin, nerves, limbs, and eyes, resulting in amputations, paralysis and blindness.

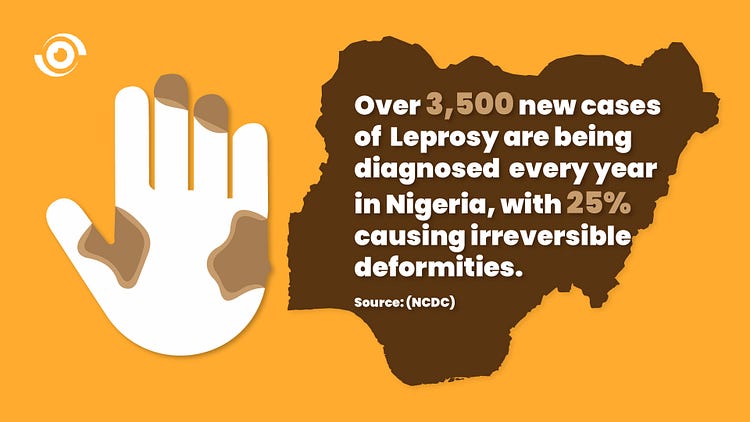

The 44th World Health Assembly (WHA44) called for the elimination of leprosy as a public health problem at global level, by the year 2000 and despite attempts to eliminate this disease, 202,185 new leprosy cases were registered globally in 2019, according to official figures from 159 countries from the 6 WHO Regions. In Nigeria, leprosy is still prevalent and remains a significant public health concern with over 3,500 new cases being diagnosed every year in the country, according to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, with 25% of them causing irreversible deformities.

Managing leprosy in Nigeria

In managing leprosy, one effective way of preventing the disease from causing irreversible deformities is early detection. Early detection and treatment with Multidrug therapy (MDT) as recommended by WHO remains the mainstay of leprosy control. When detected early, the disease does not lead to mutilation and permanent deformities or disabilities which often results in stigma associated with the disease. But lack of awareness about the disease and its symptoms among the populace, especially in the rural, hard-to-reach areas often makes early diagnosis difficult.

Established in 1989 by the Government of Nigeria, the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme (NTBLCP) has the responsibility of reducing the burden, socio-economic impact, transmission of tuberculosis and leprosy in the country. They are to provide appropriate rehabilitation of persons affected by leprosy within the country. With support from The Leprosy Mission Nigeria, the Nigerian government has continued to ensure that leprosy treatment is free in all government approved centres across the country. This is targeted at mitigating the impact of the disease among the vulnerable in the society.

Globally, initiatives like the End Fund work to ensure people at risk of NTDs can live healthy and prosperous lives with over one billion dollars spent in treatments from 2012 to 2019. One of its new board members, Professor Moses John Bockarie said getting “initiatives like Global Fund for HIV, AIDS & TB and child immunisation programmes to recognise the value of synergistic activities to achieve universal health coverage,” will help address the negative impact of leprosy and other NTDs in Africa.

Ending stigma, improving life

The socio-economic impact of leprosy may be a greater source of suffering to some individuals than the disease itself. Those affected by the disease continue to experience intense stigma and discrimination due to myths and superstitions associated with fear of the disease. Globally, stigma remains a huge barrier to zero leprosy in terms of prevention, treatment, case management and prevention of disabilities. In addition, it has a severe impact on the mental wellbeing of persons affected and their families as it impairs their quality of life in various ways.

Persons with stigmatising conditions experience problems in virtually all spheres of life, ranging from their marriages to their jobs. Community interaction such as social relationships and friendships are also affected. Their families may experience reduced educational opportunities because of stigma, leading to further inequities. All these negative effects result from poor community awareness of the disease, as well as the myths, and misconceptions around it.

Leprosy is an infectious disease of global health concern therefore controlling it is a collective responsibility. To create global awareness about the disease, WHO recognises the last Sunday in January as World Leprosy Day. The theme of the 2021 World Leprosy Day is, Beat Leprosy, End the Stigma. The progress made by the joint efforts of the NTBLCP, The Leprosy Mission Nigeria and other partners to curb the disease and end the stigma associated with it in the country can be consolidated with more community awareness about the disease. The poor awareness about leprosy and the associated stigma that comes with it means that most cases are not detected early until the disease is in the advanced stage, often leading to permanent disabilities. So, community awareness, hinged on simple, repetitive information to discourage discrimination against infected and affected persons must be prioritised. Annual training of health workers in various primary health centres in hard-to-reach areas by epidemiologists will enhance early detection of the disease. Private Patent Medicine Vendors like the one that Aisha went to after she first noticed her skin patches, should also be trained to recognise the disease and refer early to health facilities for prompt treatment.

Living with leprosy or life after the disease has always been a challenge, says Aisha. The stigma associated with the disease makes life difficult and forces them to spend most of their lives in isolation, denying them their fundamental right of association in the society.

On 8th of January 2021, President Mohammed Buhari assented the Disability Bill, and inaugurated the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities. It is imperative that citizens hold the government accountable for this commitment to ensure full implementation of the law. It must empower and reintegrate people living with disabilities back into the society to achieve their full potential.

The camp in Alheri Community is severely deteriorated as the facility lacks basic amenities such as WASH facilities and electricity. The clinic inside the camp needs to be equipped with essential medications. According to the village head, Malam Ali Isah, the community has already lost more than sixty people as a result of the lack of proper medication to treat leprosy patients.

Professor Bockarie believes adopting models that are working in other African countries will help address some of the challenges posed by NTDs such as leprosy. “The National immunisation day in Sierra Leone has been used to promote and facilitate mass drug administration activities, increase treatment and immunisation coverage for many diseases”, he said. But for this to be sustainable, government must take ownership from conception to implementation.

The government must ensure that Aisha and others living with and affected by leprosy are not ostracised and forced to live in leprosy camps. Measures must be taken to ensure that they are reintegrated back into society so that they can live life to the fullest.