By Joyce Chimbi (Lead Writer)

Augustus Omondi suffered a persistent cough and intense night sweats that lasted for almost one month in late 2018. However, it was the significant weight loss that alarmed him. He was afraid that he might have contracted HIV/AIDS. “Even after several visits to the hospital, I was getting worse. After several tests, health providers at Mama Lucy Hospital in Nairobi said I had drug-resistant TB. It was the second time I was testing positive for TB, but this time it was much more serious.” Omondi was put on another nine months of treatment; however, he was given a daily injection for six months and oral tablets throughout his treatment. “The side effects were severe, including nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite, but I pressed on,” he added.

Kenya’s struggle with TB burden

Although preventable and curable, tuberculosis (TB) remains a deadly infectious disease and a severe public health challenge in Kenya, it affects at least 120,000 people annually. It is the fifth leading cause of death, accounting for 3.2 percent of all deaths recorded in 2020. The Ministry of Health estimates that the burden of TB is 426 cases per every 100,000 people.

The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks Kenya among the 30 countries with a high TB burden, collectively accounting for more than 86 percent of global TB cases. Kenya is one of the 14 countries globally to have appeared in all three lists of high-burden countries for TB, TB/HIV co-infection, and Multi-Drug Resistance TB (MDR-TB). MDR-TB is a more severe form of TB that is resistant to first-line therapy. Due to its high level of infectiousness, it has been described as ‘Ebola with wings’. In Kenya, an estimated 62.5 percent of drug-resistant TB patients lose their jobs as a result of the disease.

Innovative treatment addressing drug-resistant TB

TB treatment has typically been administered by Daily Observation Therapy (DOT), an approach in which patients take medication, including injectables, while under close supervision of a healthcare provider. However, in 2020, two new treatment initiatives were introduced; the Kenya Injectable Free Regimens (KIFR) and Latent TB Infection (LTBI) Treatment Policies to achieve the goal of a TB-free Kenya by 2035. The latent TB policy guides the treatment of latent TB infections, and the new drug regimen will be made available to people who are at risk of developing active TB.

Without treatment, one in every ten patients with latent tuberculosis will develop active tuberculosis and spread the bacterium to others. People living with HIV are 20 to 37 times more likely to progress from latent infection to active TB, repeating the TB transmission cycle.

Njeri Wanjiku, a clinical officer at Kiambu Level Five Hospital, said that the first case of extensive drug-resistant TB was detected in 2007. Since then, the country has struggled to prevent and treat MDR-TB. At the time, MDR TB treatment was completed over 20 to 30 months, depending on the severity of infections. Treatment was in the form of an injection and five types of daily tablets. By 2017, the treatment period was about nine to 12 months, with a daily injection for at least four months and oral tablets throughout the treatment period.

Peter Njogu Kimani, a medical expert in respiratory diseases domiciled at the Ministry of Health, said, “KIFR policy guidelines are centred on patient-friendly all-oral treatment free from any injections in line with WHO’s recommendation to eliminate injections from MDR-TB treatment regimen to improve treatment outcomes. We have determined that because TB treatment is a tedious, long, and painful process for TB patients and those with MDR-TB, many do not complete their treatment. Others fail to take medication as prescribed. They might come for an injection today and fail to show up for several days.”

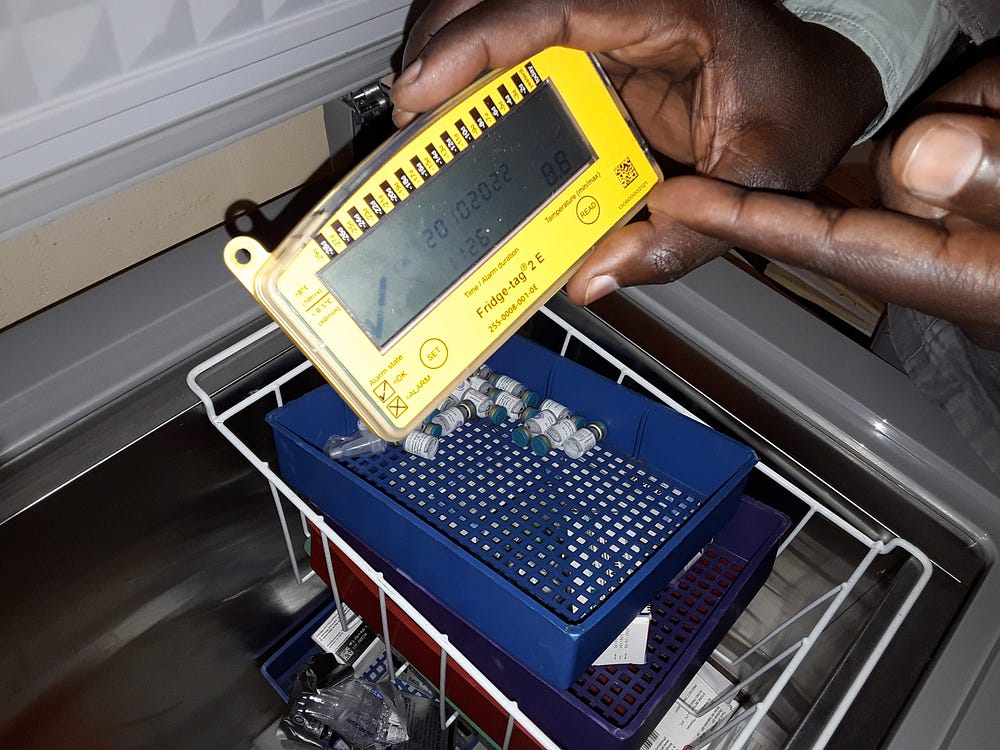

In addition to a cumbersome treatment regimen, infrastructure-related challenges hampered access to TB treatment for those with drug-resistant TB. An estimated 26 percent of Kenya’s health facilities have no access to electricity, and only 15 percent have access to stable, reliable power. Injectable medicine requires a reliable cold chain or storage facility to preserve injectable drugs. Off-the-grid health facilities do not have a cold chain and cannot store injectable medication. This means that MDR-TB patients had to travel long distances to sub-county hospitals for uninterrupted treatment. Switching to an oral treatment regimen means that all health facilities, even resource-constrained dispensaries in remote rural areas, will be able to reach a previously inaccessible population with the critical MDR-TB treatment. Today, MDR-TB treatment is available on demand from low-level dispensaries to high-level referral hospitals.

The injectable-free drug or a combination of oral tablets was first used in Kenya in mid-2018. However, the country fully transitioned in June 2020 under the National Tuberculosis, Leprosy, and Lung Disease Programme. By September 2020, an estimated 774 MDR-TB patients had received the injection-free treatment regimen. The oral regimen is available for all new MDR patients free of charge.

The KIFR significantly improves treatment outcomes and quality of life for those affected. It provides patients with MDR-TB a shorter, painless and convenient treatment period compared to traditional regimens. Other benefits include improved adherence, reduced side effects, enhanced effectiveness and better tolerability.

According to Wanjiku, “Injectable-free anti-TB drugs are patient-friendly. We are now seeing better treatment outcomes, such as reduced infections and deaths related to TB, because people can take oral medications in the privacy of their homes, and they can receive up to three months’ worth of drugs at a go. We do not have to do DOT or observe patients take treatment daily. We have a system where drugs are coded every day. A patient is now only required to send the code at the back of the tablet they are taking that particular day to their health provider through a toll-free SMS message, saving time, money and providing privacy for the patient. Patients are going about their normal routines uninterrupted”.

Improved outcomes and lives changed

Since adopting the new regimen, Kenya has made significant strides in combating TB. It has reduced new TB infections by approximately 32 percent, far exceeding the global target of 20 percent. The country also recorded an estimated 44 percent reduction in TB-related deaths. Kenya has also transitioned out of the 30 high MDR-RR TB burden countries.

In 2021, Margaret Waceke tested positive for TB for the second time in three years. She dropped out of TB treatment in 2019 and presented with the more severe drug resistance TB strain in May 2021. “I was very familiar with TB. My sister used to receive daily injections, and I was very worried and concerned about the injections. But I was very shocked when the nurse gave me tablets enough to last me for one month. After that, I would receive enough drugs for three months. Although it is difficult to take medication every day, the treatment was much better than before. I felt no pain or side effects; no one knew I had TB because I took my medicine in the privacy of my home, and I never missed work to receive treatment. I am paid based on the days worked, so this was a very easy and convenient process. The entire TB treatment programme has changed in so many ways,” said Waceke.

Progress amidst challenges

Despite significant progress, Kenya continues to face challenges that limit its efforts to eradicate TB. While the availability, accessibility, and patient-friendliness of TB treatment has greatly increased, a large percentage of TB cases continue to go undetected, eventually progressing to active TB cases.

Every year, at least 40 percent of TB cases go undiagnosed. For example, while Kenya had an estimated drug-resistance TB incidence of 2,200 cases, only 508 cases were diagnosed. As a result, Kenya’s TB diagnosis recently entered a new phase of molecular testing, which is faster, cost-effective, and confirms drug-resistant TB diagnoses. It is expected that as more cases are accurately identified, and patients are placed on patient-friendly anti-TB medication, preventive measures are fortified, and treatment avenues are solidified. This will help Kenya get closer to its goal of eliminating the silent killer by 2035.