By Joyce Chimbi (Lead Writer)

In 2014, when Edith Mumbi’s twins were born, they had a low birth weight and were admitted into the neonatal unit at a public health facility in Nairobi, Kenya. Mumbi was discharged two days after giving birth but visited her babies daily to breastfeed them. “The babies showed signs of improvement before their situation quickly worsened. I was using a matatu (public vehicle) from home to the hospital and because they are very congested and my immunity was low, I caught TB and passed it to my babies. By the time it was discovered that I had TB, one baby had passed on” she recounted.

Neonatal mortality remains an urgent primary health challenge that contributes to an estimated 45 percent of the under 5 mortality rate in Kenya. According to Kenya’s Ministry of Health, the main causes of neonatal mortality include low birth weight, congenital malformations, neonatal sepsis, infections and pre-term birth complications. Maternal related factors also contribute to neonatal mortality.

Over time, Kenya has made some progress towards reducing neonatal mortality from 33 deaths per 1000 live births in 2003 to 22 deaths per 1000 live births in 2014, according to the 2014 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2014). This is the latest national data available as the DHS 2022 survey is currently being conducted. The World Population Review has placed Kenya’s infant mortality rate at 31.5 per 1000 live births in 2022. The methodology used may however defer from that of the DHS.

Practising task shifting task sharing

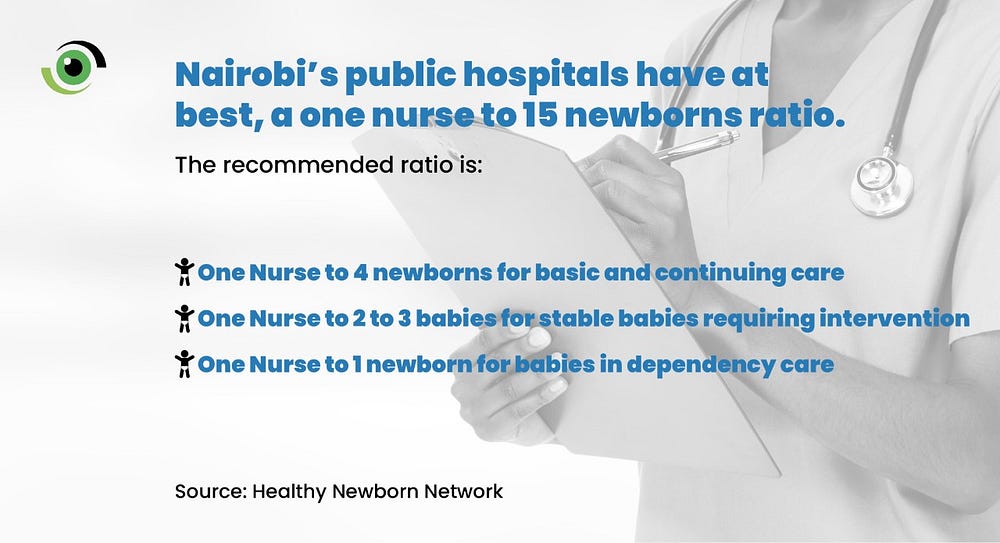

Kenya is one of 36 countries in Africa with a serious health worker shortage, especially neonatal nurses. Access to antenatal, emergency obstetric and neonatal care can ensure neonatal survival, however Leah Omrunga, a nurse at Mbagathi Hospital in Nairobi said that in the absence of the recommended newborn to nurse ratio, nurses, who are in constant close interaction with newborns, may find it difficult to offer the required care. Nairobi’s public hospitals have at best, a 1 nurse to 15 newborns ratio, which could compromise the quality of care provided — as it is in sharp contrast to the recommended ratio of 1 nurse to 4 newborns for basic and continuing care, 1 nurse to 2/3 babies for stable babies requiring intervention and, 1 nurse to 1 newborn for babies in dependency care, as recommended by the Healthy Newborn Network.

To address the service delivery gaps, “in 2014/2015 we started to informally embrace the task shifting task sharing model in public health facilities,” added Omrunga. Senior and more experienced nurses began by training nursing students and casual workers to undertake some of the less technical work that was still being undertaken by technical staff. It was the beginning of delegating responsibilities to close the human resources for health (HRH) gap.

Besides attending births, the other main responsibility of a neonatal nurse includes taking care of newborns, directly monitoring the health of a newborn, teaching new mothers how to breastfeed and care for their infant, as well as measuring and weighing an infant. According to Omrunga, “A senior nurse would delegate nursing tasks such as weighing a baby and teaching mothers how to breastfeed to nursing students. Senior and more technical staff started increasing the amount of time spent doing more technical nursing duties such as directly monitoring the health of a newborn”.

The health workers were so focused on ensuring that babies received the necessary care that the impact of the informal system wasn’t tracked. But the authorities did notice a difference and moved to formalise it. Thus the Task Sharing Policy of 2017–2030 and the Task Sharing Policy Guidelines in Kenya’s newborn units were developed. These were actionable models for nurses, nutritionists, nursing students, casual workers and doctors to boost progress towards the elimination of neonatal deaths.

Formalising the task shifting task sharing model

The neonatal task shifting tasking sharing model is practiced in Kenya’s sub-county hospitals, county referral hospitals and national referral hospitals because lower-level health facilities do not have standard maternity wings for labour, delivery and postnatal care services. The guidelines outline how nurses can navigate a lack of prescribed cadres in service delivery and still provide equal or higher quality newborn care and treatment than specialists. The policy highlights how, through adequate training and supervision, neonatal nurses can collaborate and effectively prevent and respond to life threatening situations in newborn units.

The guidelines also make it mandatory for public health facilities to address the challenges of insufficient neonatal nurses, a heavy workload and regular life-threatening medical emergencies in newborn units by making efficient use of existing neonatal human resources.

Under structured supervision, technical staff were trained to initiate and maintain newborn death preventive measures such as educating mothers on recommended sleeping positions to avert sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Nutritionists were engaged to initiate and maintain nutrition interventions for mothers and their babies. Nursing students were trained to educate mothers on infant growth and development.

Samwel Makhoha, from the Nursing Council of Kenya said it is all about expanding access to services, while providing the best structure for routine newborn care as well as handling at risk babies and emergency situations. “In the past, an emergency or new admission would bring newborn care work to a standstill. Staff would be running around, and it was not clear who was doing what, and what was left undone as others rushed to attend to the emergency. Today, we have a structure that helps ensure that all elements of newborn care are manned and implemented under very clear guidelines,” he said.

Formalising task shifting task sharing guidelines has reduced the downward spiral in health indicators among neonates, but the model is not without its challenges. Improving the quality-of-care neonates receive requires specialised care and despite the delegation of tasks, there is still a need to increase the number of specialist neonatal nurses. “The model has helped create a routine, predictability of duties and improved response to emergencies, but it has not addressed the issue of limited staff and resources, critical pillars towards desirable newborn health outcomes,” said Makhoha.

“Without addressing the ratio of nurses to babies, our neonatal care systems are still not strong enough to significantly reduce and sustain a reduction in neonatal mortality. The workload is still very high, you still have the same number of tasks being undertaken by the same number of staff,” he added. Despite the existence of over 50,000 registered nurses in the country, only 17,000 work in the public sector.

Caring for newborns requires specialist care that overworked and overloaded nurses cannot provide. Babies at this early stage are very vulnerable and require experienced hands-on specialist care round the clock. Makhoha would like the government of Kenya and health and development organisations to invest in the much-needed staffing resources required to provide a conducive environment that would provide every newborn with an equal chance of survival. This investment could also help put Kenya on track to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.2 which aims to reduce neonatal mortality to as low as 12 babies in every 1,000 live births.

We have gone through a similar situation. Will share our experiences, if allowed.

Please go ahead and share your experience with us. Send an email to torchlightafrica@nigeriahealthwatch.com. We’d love to hear from you.