By Farai Shawn Matiashe (Lead Writer)

Zimbabwe’s economic crisis has exacerbated malnutrition among children in the country. In Harare and Bulawayo provinces, GOAL Zimbabwe, in partnership with the two City Councils and the Health Ministry, is helping to improve child nutrition by training nurses and mothers to identify malnutrition early and providing cash transfers to families to ensure that they have adequate food after the treatment.

Lynn’s story

Lynn Kamushinda knew something was terribly wrong with her three-year-old daughter, Angela, when she started vomiting and complaining of stomach pain. Angela also had diarrhoea and had lost a lot of weight, so a community health worker advised Lynn to take her daughter to the Kuwadzana Polyclinic.

Kuwadzana Polyclinic is one of the many clinics in Harare and Bulawayo, supported by the Linkages programme which aims to improve child nutrition in the two provinces by providing training to nurses and mothers to identify malnutrition early. The one-year programme began in 2021 and is being implemented by GOAL Zimbabwe in partnership with the two City Councils and the Health Ministry. It distributes Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) tapes to mothers and teaches them how to use it.

The programme also helps train nurses in the clinic, as well as community health workers who serve the high-density suburbs around the clinic, on how to identify and treat severe acute malnutrition (SAM), and Moderate Acute Malnutrition (MAM) in children under the age of five. For moderate cases, they give the children ‘plumpy nut’, (a peanut-based paste used to treat malnutrition), also known as ready to use therapeutic foods (RUTF) and super cereal porridge to improve nutrition. They refer severe cases to hospitals like Parirenyatwa Hospital for admission and further treatment.

When Lynn and Angela arrived at the polyclinic, which serves a population of 173,313 people, after a series of tests and a physical examination, it was determined that little Angela was underweight and malnourished. She was placed on a diet of plumpy nut for three months, and nutritious cereal for another three months and now weighs 14.8kg; a marked improvement from the 12kg she weighed last year.

“My daughter’s appetite has improved. I am now preparing to enrol her in pre-school. Her situation was so dire that she could not go to school,” says Kamushinda, who lost her source of income when Zimbabwe went into COVID-19 lockdown in April 2020.

Cash transfers to alleviate poverty

Most breadwinners like Kamushinda and her husband work in the informal sector and were left without any form of social support when they lost their jobs. The Linkage programme, recognising poverty as one of the drivers of malnutrition, introduced a cash transfer component to the programme.

The cash transfer of up to $75 (Z$63,000), enough to feed a family of five for a month, is given to every family whose child has been enrolled in the programme to ensure that they have adequate food after the treatment. The duration of the cash transfer is dependent on the family’s peculiar situation. According to Finance Maribha, a sister in-charge at the Polyclinic, the cash transfer also plays a pivotal role in encouraging mothers to continue visiting the clinic for routine check-ups, thus reducing the defaulter rate.

Community health workers to reach the hard-to-reach

In Bulawayo, Peggie Ndowora, a community health worker, distributes MUAC tape to mothers in Nkulumane, a high-density suburb, and teaches them how to use it. “We encourage mothers to give children the traditional foods which are nutrient dense,” she said. Ndowora also checks for signs of malnutrition among children in the community. She refers any suspected case to the nearest clinic.

“When it comes to early identification of acute malnutrition, I can confirm that MUAC tapes are good,” said Kudakwashe Zombe, a nutrition expert. Angeline Zengeya, another nutritionist, said distributing MUAC tapes to mothers places them at the centre of the malnutrition screening process. “This is important for the early detection of SAM and MAM cases,” she added.

But for Zengeya, although the MUAC tape is effective for detecting extreme cases of malnutrition, it cannot give further details such as what disease the child will be suffering from. “Furthermore, a simple arm measurement does not differentiate between kwashiorkor or protein malnutrition,” she opined. Zengeya believes that the government needs to take a multi-sectoral approach to tackling malnutrition.

“Strong, public, private partnerships and cooperation with civil society organisations should be promoted in order to tackle malnutrition.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend that young children should be exclusively breastfed until the age of six months, and then nutritious solid food should be introduced alongside breastfeeding for up to two years. But Ndowora said that some mothers do not follow these guidelines.

Not enough time

In Bulawayo and Harare Provinces, about 671 children have been admitted for treatment of malnutrition between June 2021 and March 2022. So far, 323 children have been successfully treated; the rest are still receiving treatment. However, there is a high rate of defaulters. For reasons ranging from long distances to the clinics to poor health-seeking behaviour, some mothers fail to take their children back to the health facilities for child growth monitoring check-ins. To help mitigate this, Jenipher Nkhoma, a community health nurse said they take essentials such as plumpy nut and Vitamin A to those who are in hard-to-reach areas. She reported that there is now consistency and continuous child growth monitoring in her area of jurisdiction because of the outreach programmes.

Valeria Nkhungwa, a nutritionist responsible for the suburbs of Kuwadzana and Waterfalls, expressed concern over delays with the cash transfers reported by the recipients which she said was the fault of the service providers. Another concern was the fact that mothers were reported to divert the cash meant to ensure the full recovery of the child to other purposes. “Some mothers are abusing the cash transfers. There is a need to consider distributing vouchers instead of cash. It can be one voucher for food and another for medicine,” Nkhungwa suggested.

She also worried that the one-year duration of the project is too short. “We fear that some mothers will be stranded when the programme ends,” she said.

Sustaining the momentum

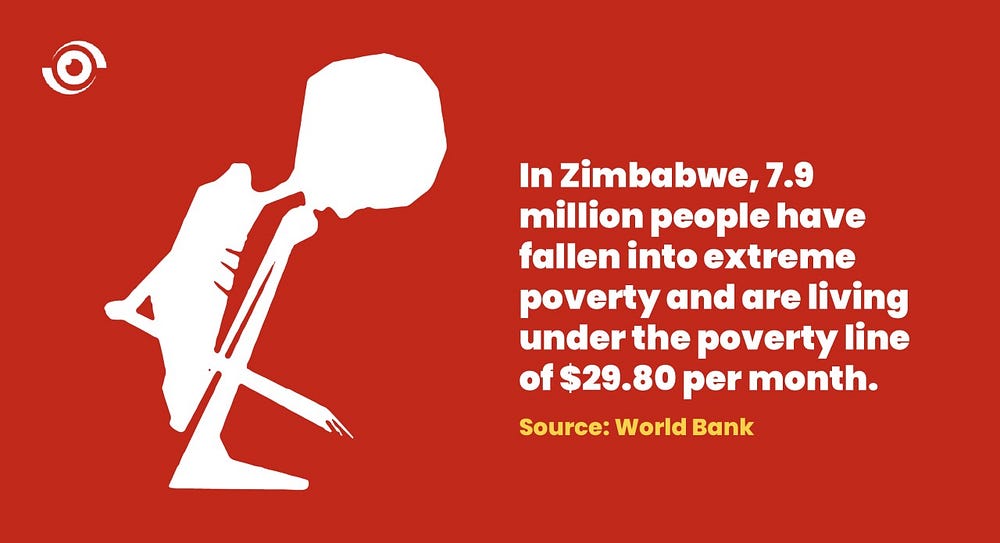

Zimbabweans are grappling with the worst economic crisis in decades; food scarcity, poverty and hyperinflation are severe. According to the World Bank’s social and economic update, 7.9 million people in Zimbabwe fell into extreme poverty in the past decade, which means that they are living under the poverty line of $29.80 per month. The United Nations’ World Food Programme also estimates that 5.3 million people — in both urban and rural areas — were food insecure between January and March 2022, which is ironically the beginning of the harvest season.

As a result of the country’s economic and food issues, most families in both urban and rural areas are unable to feed their children. This has exacerbated malnutrition among children which was before now being fuelled by inadequate knowledge, cultural-and-gender norms, insufficient quality nutrition services, and food legislation not complying with international standards, according to the Zimbabwe Annual Report 2021.

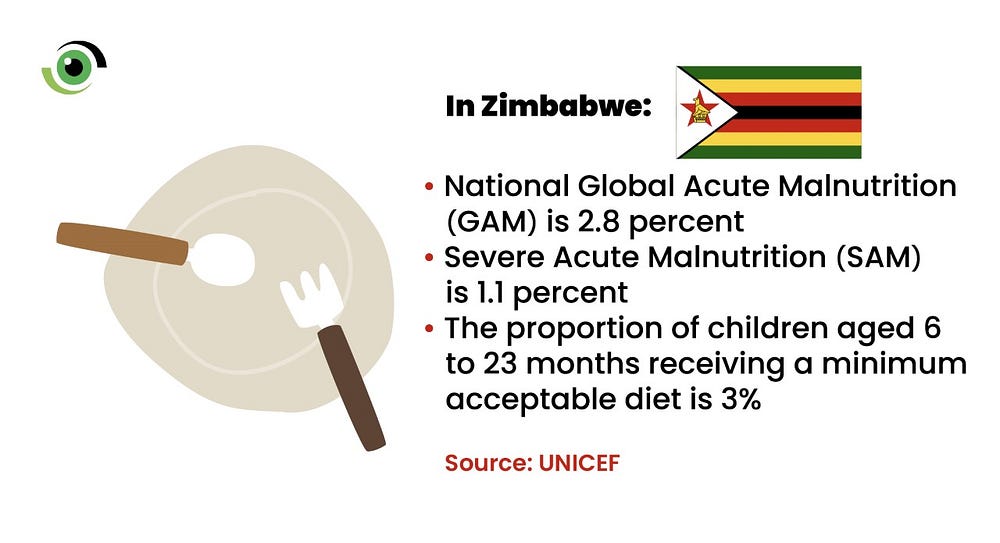

This 2021 report by the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee showed a national Global Acute Malnutrition (GAM) prevalence of 2.8 percent, with a Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) rate of 1.1 percent. The proportion of children aged 6 to 23 months receiving a minimum acceptable diet, was low at 3 percent.

However, the Zimbabwe Annual Report 2021 indicated that stunting rates have decreased in the last 15years in the country — from 31% in 2007, 39 per cent in some rural areas, to a national rate of 23.5 per cent. This could serve as evidence that Linkages and other such interventions are recording some positive results. It is imperative that the government of Zimbabwe and development partners carry out a formal study to assess the results of these interventions and leverage this momentum to sustain and possibly, improve on them to effectively address nutrition vulnerabilities among children.

*Some names have been changed to protect some identities.

First’congrats on your milestone iniyiative to showcase state of PHC in Nigeria. Kindly mail to me the comprehensive Report of ‘State of PHC Service Delivery in Nigeris’.I would like to review that frame viz a vis your treatise on nutrition in Zimbabwe. Sincerely yours. Dr. Ibanga Inyang .MPH.FWACp